Finnish in-work poverty in a European comparison

Policy brief 5/2019

Olli Kangas

- In-work poverty (IWP) in Finland is among the lowest in the EU member states.

- In the 2010s the EU IWP rates for most population groups have increased.

- In Finland there are downward trends in the IWP rates measured by gender, age, different household types, intensity of work, employment status and country of origin.

- The most vulnerable groups exposed to IWP in Finland are the same as in the other EU countries: immigrants from non-EU28 countries, the self-employed, and low work-intensity households – single mothers, in particular.

- Those policies that directly or indirectly fortify the adult earner model – the model that facilitates both genders in all family situations to fully participate in paid work – are of great importance in reducing IWP.

Since the 2008 economic crisis, poverty in Finland has been in decline

In the 2010s the Finnish in-work poverty (IWP) rates have been the lowest in the EU and they have been in decline (3.8% in 2012 and 2.7% in 2017). In many other countries, IWP has increased, and it ranges from the lowest Finnish values to the highest values found in Romania (17.9%).

Since the international 2008 economic crisis, inequality and poverty in Finland have been in decline: the Gini-index went down from 28.4 in 2008 to 27.7 in 2017. The corresponding numbers for poverty rates were 13.9% in 2008 and 12.1% in 2017.(1)

The same trend is visible in the IWP rates. The risk of IWP has fallen among the self-employed, in particular (from 14.1% in 2012 to 11.5% in 2017). On average, in the EU the IWP rate for the self-employed is much higher than in Finland (22.2% in 2017). The same goes for employees (in Finland 1.3% vs. the EU average 7.4% in 2017). However, in Finland the relative risk of IWP is 8.8 times greater among the self-employed than among employees. The corresponding figure is 3.0 for the EU28.

Table 1, depicts the most recent developments by household types. We can see that the rank-order of vulnerable groups in the EU and Finland follow the same order: single parents, single adults, couples with children and couples without children. The rank-order indicates that, whereas in most European welfare states the dual-earner model is an effective guarantee against in-work poverty, being a single-earner household increases the risk of being poor. Also, in Finland single parents had rather high IWP rates up to the year 2014, but by 2017 the rate was much lower. However, the poverty risk of a single parent is three times greater than that of a couple without children, and twice as high as a couple with children.

2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||

| EU average | Single person | 12.6 | 13.1 | 13.5 | 13.2 | 13.9 | 13.4 |

| Single person with dependent children | 19.8 | 20.2 | 20.0 | 19.9 | 21.6 | 21.4 | |

| Two or more adults without dependent children | 5.7 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.1 | |

| Two or more adults with dependent children | 10.1 | 10.0 | 10.5 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 10.6 | |

| Finland | Single person | 7.0 | 7.3 | 5.7 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 3.9 |

| Single person with dependent children | 9.5 | 11.6 | 12.8 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 5.7 | |

| Two or more adults without dependent children | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 1.6 | |

| Two or more adults with dependent children | 3.2 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 3.0 |

Table 1. In-work poverty (%) by household type in Finland and the EU in the 2010s.

Work intensity matters

One obvious explanation for IWP is work intensity, and at first glance, the explanation for the low Finnish IWP rates is that in Finland the share of part-time work is much lower than in most other countries. Finland can be characterised as a country with dual-earner households and people with full-time jobs. These employment characteristics effectively combat poverty in general and IWP in particular.

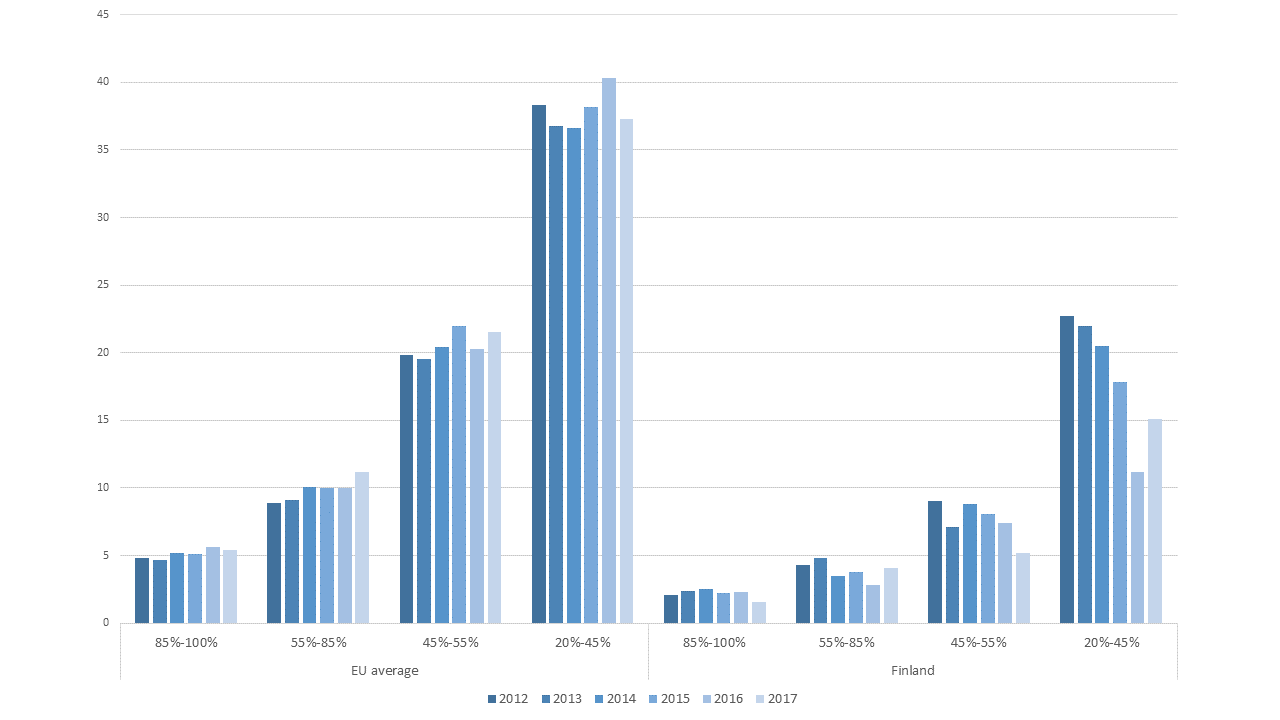

The level of work intensity correlates with IWP. As Figure 1 indicates, In Finland, there is no difference between the very high (working 85%-100% of full-time hours) and the high work-intensity groups (IWP rate 2%-3%). The medium intensity group displays somewhat higher IWP risks (6%-9%). A worrying trend is that those earners in low work-intensity groups, both with and without children, have rather high poverty rates, and furthermore, since 2016 IWP has increased in this group.

Figure 1. In-work poverty (%) by work intensity; households with children; Finland and the EU in the 2010s.

In many countries, immigrants are in the low work-intensity and low-paid group and are hence the most exposed to IWP. There are many reasons for this. Often immigrants end up in low-paid jobs in services (cleaning, housekeeping, restaurants), or they obtain their livelihood from self-employment. In many countries, the risk of IWP is greatest in those occupations. Both in the EU (about 20%) and in Finland (close to 10%), immigrants from non-EU28 or other foreign countries, in particular, have the highest in-work poverty risks.

Societal changes may raise the poverty rate in Finland

The low IWP rates in Finland are a result of several underlying factors that are interlinked. First, employees are highly unionised and they can promote their interests via comprehensive collective agreements. The comprehensive social security system increases threshold wages and there are also in-work benefits that mitigate low income caused by low work intensity/low pay. One crucial factor for the low IWP rates has been the prevailing dual-breadwinner and full-time employment model. The full-time employment pattern also effectively prevents IWP. Finally, the share of immigrants (usually employed in low-paid jobs) has been low in Finland.

However, there are several challenges that may change the situation. New forms of contract work and IWP risk increasing immigration may raise the IWP rates. Increasing single parenthood may raise the. Maintaining a low degree of IWP requires flexible and diversified income transfers and a wide range of childcare, other family-related, social care services to allow employment and parenthood to be combined.

Policy recommendations

- When seeking flexibility in the labour market, it is important to have a coordinated bargaining system guaranteeing decent wage levels.

- Universal care services guarantee the continuation of the defamilised adult earner model, which gives everyone the possibility to fully participate in paid work and effectively prevents in-work poverty.

- Specific inclusive programmes targeted at vulnerable groups should be made more effective in order to enhance higher employment rates and higher work intensity in these groups as well.

More information:

professor Olli Kangas, University of Turku (firstname.lastname@utu.fi)

This Policy Brief is a shortened and modified version of a more extensive study by Olli Kangas and Laura Kalliomaa-Puha (2019): ESPN Thematic Report on In-work poverty – Finland, European Social Policy Network (ESPN), Brussels: European Commission.

See also Airio Ilpo (2008): Change of Norm? In-work poverty in comparative perspective. Helsinki: Kela and Lohmann Henning. and Marx Ive. (eds), Handbook on In-work Poverty. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

References:

1) Findikaattori, (2019a) Tuloerot 1966-2017 [Income inequality 1966-2017]. [retrieved 11 August 2019].

Findikaattori (2019b) Pienituloisuusaste 1966-2017. [Poverty rate 1966-2017]. [retrieved 11 August 2019].