Tapani studies Ugandan rainforest wasps and their species richness. Today’s blog post is a mishmash of eradicated elks, returning wolves, and the conflicts that occur when nature changes. [Originally posted in Swedish. Finnish version also available]

Sometimes we need reminding how well off we are. Mattias Kanckos recently wrote an interesting article on Finnish nature and the state it is in (Katternö 1/2018, 52-53; SW / FI). What was refreshing, and inspired this text, was that he didn’t focus on problems. Overexploitation of the forest was mentioned but only in passing. Instead, the focus was on the fact that almost all large mammals and birds are now much more numerous than they were a century ago.

What’s this, write something positive related to nature conservation!? And remind the reader that problems that seem serious in Turku are perhaps less relevant in other parts of Finland? This alone would suffice as a reason to address these issues here. But the topic is also interesting since the recovery of Finnish nature hasn’t only had positive effects. It has also led to conflicts, when people have suddenly had to get used to species which have returned after a long absence.

There is currently a debate on wolves going on in my home area, with all the newspaper comments (and occasional extremes) that are typical of heated topics. Mattias Kanckos’s text addressed the background to this situation. I will do the same: there’s a chapter on where all the animals disappeared from independence era Finland and a chapter on the wolf situation that has arisen when they returned – but no armchair advice on what (if anything) ought to be done.

The fall and rise of Finnish nature

First the short version. Finnish nature collapsed during the past centuries. Now it’s gradually coming back.

OK, I’m simplifying a lot. And the whole idea of there being an changeless “natural state” which is now being returned to is problematic. But in the context of the history of Finland’s large mammals and birds during the past centuries, it is not too far from the truth.

The collapse happened due to us humans (anyone surprised?). During the 19th and 20th centuries we managed to largely eradicate:

- elks

- swans

- lynxes

- wolves

- bears

- forest reindeer

- white-tailed eagles

Note that these are examples, I could continue the list for quite a while. Common to all of these is that they were numerous and widespread, disappeared almost entirely, and are now gradually returning.

The recovery is also thanks to humans (if thanks is the right response to someone mending their ways). Legal protection and changed attitudes turned the trend for the above species. We have also received newcomers who were rare or absent in the past, such as roe deer, white-tailed deer, hares, blue tits and blackbirds.

Elks are taken for granted in Finland (yes, elks not moose). And rightly so, there are at least 80 000 elks in our country despite our hunting about 50 000 every year. What is often forgotten is that we once managed to hunt elks to the brink of (local) extinction: at its worst in the 1920s there were probably only a few hundred elks in the entire country. Even in the 40s most Finns thought of elks as rare creatures of the wilderness (6000 elks in Finland), and it’s only my generation born in the 80s that has again got used to having tens of thousands of elks in the forest. The lack of shovel-type antlers can also be blamed on the past: the scarce 1920s elks mostly had non-palmate antlers.

Swans have a very similar history to elks. Nowadays the whooper swan is our national bird, with at least 8000 breeding pairs. To me (born in the 80s) the idea of a Finland without swans is as foreign as a Finland without trees. Yet a Finland without swans is more or less what we had a mere 70 years ago: our national bird was hunted down to 15 breeding pairs in 1949.

Forest reindeer history only really differs from that of elks in one way: elks just and just survived, forest reindeer were exterminated. By the time the species was protected in 1913 the last forest reindeer had already been killed. It took decades before they returned to Finland, and even today most Finns have probably never seen one. But in the areas where they exist they seem to be doing well, and Finland now has an expanding population of about 2000 forest reindeer.

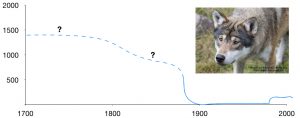

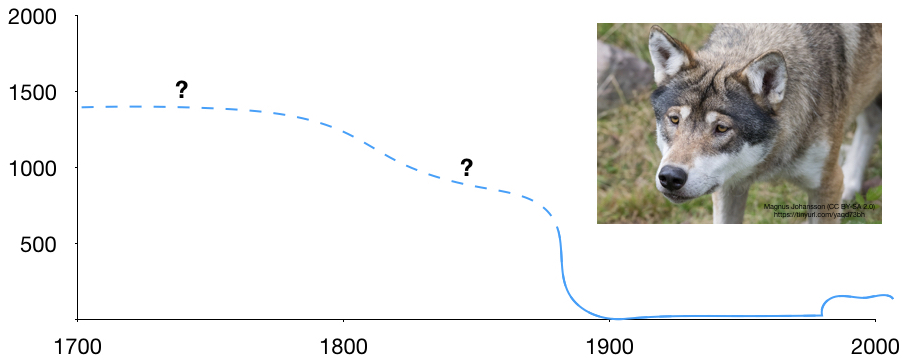

Wolves were almost entirely eradicated in the beginning of the 20th century. They remained largely absent until the 1980s, with the exception of occasional stragglers from Russia. There are still very few wolves in Finland (less than 200). This means that I belong to one of the several generations who have subconsciously assumed it’s normal not to have wolves nearby. The number of wolves has not increased for a decade, but they have (re)colonised some new areas in Finland.

Roe deer and white-tailed deer are now firmly established in Finland with a total population of over 100 000. But a century ago neither species lived in the country. To me, having spent my childhood tracking roe deer in the forest, and living as I currently do in Turku (where white-tailed deer attract less attention than seagulls), this is practically incomprehensible. Roe deer immigrated from Sweden and Karelia in the 50s and have later been helped on their way by humans. They may have also occasionally been present in southern Finland in previous centuries. The white-tailed deer was imported from the U.S. in the 1930s and 40s, partly to replace the eradicated forest reindeer, and its population practically exploded.

The exact details are open to debate (e.g. a forest reindeer was shot in 1921 in Savukoski) but the overall trends are clear. Many of our large animal species collapsed during the 19th and 20th centuries. Some like swans and elks have entirely recovered, others like the forest reindeer are still recovering. A few, such as wolves, have barely recovered at all, but still have it clearly better now than when things were at their worst.

This also means that generation after generation of Finns has grown up in an unnatural environment, thought it is normal, and then observed radical changes as “invasive species” like swans and elks have suddenly appeared. Change is normal in nature but this change has been unusually fast.

The price of recovery

In many ways this is a gratifying situation. Our large mammals and birds have it way better now than 100 years ago – to claim anything else is to ignore reality. When it comes to large animals we are gradually returning to normal (insofar as there is such a thing as a normal state in nature).

But no success entirely free of associated problems. Adapting to a new situation can be tricky, even for humans. When wolves turn up in areas with sheep and hunting dogs, conflicts are just a matter of time. Especially if everyone is unused to living with wolves. In many parts of Finland several generations have had time to grow up in the absence of wolves; you don’t e.g. use wolf-tolerant hunting methods if wolves were last seen in granddad’s days.

Why I’m focusing on wolves is that they happen to be relevant in Ostrobothnia (where I come from) at the moment. Wolves have returned there in recent years – to an area where hunting dogs run out of sight of their owners, cats are often allowed to wander in the forest and virtually no pastures are surrounded by wolfproof fences. Conflict has resulted.

What do you do then, in a situation where animals that haven’t been seen for generations return to an area and problems ensue? Up to now I’ve mainly been stating facts; I shall now leave the political and moral vacuum and write opinions.

There are two extreme opinions that can feel tempting to adopt. The first one I’ve mainly heard in larger towns and cities, and in caricatured form goes like this: “Why don’t they all move to Helsinki?”. Less exaggerated, people are advised to stop hunting, stop farming sheep.. until conflicts between wolves and humans no longer occur. The other extreme is in caricatured form “Shoot all the wolves”. Less exaggerated, wolves are seen solely as a problem: chase them away or hunt them until the problem is solved.

Both these extremes have two things in common. They are both much more often seen in caricatures of “the opposing side” than in reality. Normal, everyday people usually manage to control themselves and stick to moderation – even if the temptation to go to extremes can sometimes feel great. Both are also, in principle, genuine solutions. They would logically lead to the problem decreasing or disappearing entirely.

They also share one more trait: they are both completely unacceptable. Not only to me, but also to so many other Finns that carrying out either would in practice be impossible. We simply don’t want to carry out an apartheid, where humans live in one place and “nature” in another. Which I’m glad of: I’ve spent much of my life in both overpopulated areas such as cities (impoverished deserts where one species dominates) and protected areas such as nature reserves (fascinating communities with thousands of species, but cut off from humanity). And I’ve come to the conclusion I prefer Ostrobothnia (the forest is by your front door, not 40 minutes bus travel away).

Therefore the aim is to eradicate neither wolves nor humans, but to see to it that both have a place in Finland and in Finnish nature. This requires that problems are minimised – lest the current positive trend disintegrate into mutual recriminations and poaching.

How this is to be done is a trickier question. I can offer no ready solutions and promised not to be an armchair theorist. But whatever the solutions turn out to be, they will require some flexibility from both humans and (unknowingly) wolves. And they need to be societal solutions: asking an individual sheep farmer to protect his sheep himself would work as badly as asking each houseowner to employ his or her own police force to prevent burglaries. Conflicts with wolves have a lot in common with crime, they are both fundamentally about unwished-for behaviour which needs to be prevented or corrected.

As a random example, we can take a recent case where three wolves broke into a fur farm and killed several foxes. Solutions on the “human side” could be along the lines of proper compensation to the farm and wolfproof fences paid for out of tax funds (the farm’s fences were designed against raccoon dogs rather than wolves). On the “wolf side”, it should be noted that wolves who show such courage are either exceptionally hungry or exceptionally used to ignoring humans. Solutions will preferably be along the lines of chasing the wolves further away or otherwise making them shy again – if not (it’s easier to prevent poor behaviour than correct it afterwards) the solution risks becoming killing one of them, in the absence of better alternatives.

[update 18th March: there has been some uncertainty if these were really wolves. Wolves still seem more likely, however]

That’s as concrete as I’m going to write. The key, in any case, is to find and carry out solutions that allow both wolves and humans to live in the same area, without unacceptably large problems.

Perhaps more important than how problems are solved is believing it is possible to solve them, in a way that can (more or less) be accepted by all. Two encouraging facts can be mentioned here. First, wolves are no superaggressive mystified monsters. Wolves were studied for decades in northern Canada in traditional biologist style: tent, sleeping bag and notepad, follow the wolves wherever they go and write down what they do. The greatest “danger” consisted of the wolves wanting to play with the sleeping bag. Second, neither are the Finns who actually meet wolves nature-hating monsters. Of course problems are pointed out when they arise, but during the past 50 years species after animal species has regained its former place in the nature of Finland, and after a bit of an adjustment period everything has gone more or less smoothly.

Cubs being studied. © Dave Mech

We learned to live with elks, despite forest damage and traffic accidents. Our change of attitude regarding swans was so complete that it’s nowadays unthinkable to hunt them. During my lifetime bears have become almost normal in northern Ostrobothnia; soon our coexistence will be as common sense as in Kuusamo. The same will happen with wolves too.

In conclusion

We live in difficult times with a too intensive forest use and an ongoing global mass extinction. But we also live in a golden age where large mammals we thought were gone forever are once more seen in the forest. When met with new challenges, it is worth looking back and seeing how much has actually improved.

I take it for granted there are elk and roe deer in the forest – because that’s how it was during my childhood. My daughter will take bears and hopefully also wolves for granted – for her it will be the new normal. What I hope is that she’ll have as much fun tracking wolves and forest reindeer as I’ve had tracking roe deer and elk, and that she’ll do so near her home in a viable countryside.

If we are as good at solving problems as we have been the past century, I’m confident this will be the case.