Long COVID – an inflammatory consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection?

Throughout the history of humankind, we have been living in a constant battle against bacteria, viruses, and parasites. Our immune system has evolved to protect our bodies against these threats. But what happens when the defenders start causing havoc in the host

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus two, or SARS-CoV-2, as we have learned to know it, is a virus causing COVID-19 that spread across the world from the beginning of 2020. First, healthcare systems needed to address the acute threat of the disease by developing guidelines for social distancing, using masks, and managing supportive care. Second, researchers developed vaccines against the virus in a record time. These measures helped countries contain the massive damage of the disease to society.

However, many people – especially people with preexisting conditions and older people – got severely ill or died of COVID. The disease caused worldwide social isolation and the regression of culture, affecting hundreds of millions of people. Furthermore, after a while, physicians noticed that some people didn’t recover after the initial infection. The long-lasting symptoms were of a wide variety. Fatigue, shortness of breath, difficulty thinking or “brain fog”, and irregular heart rhythm were the most common. Patients named the condition “long COVID”. The medical community was skeptical of the biological foundation of the condition at first. However, the consensus started to change after persistent lobbying by patient advocate groups.

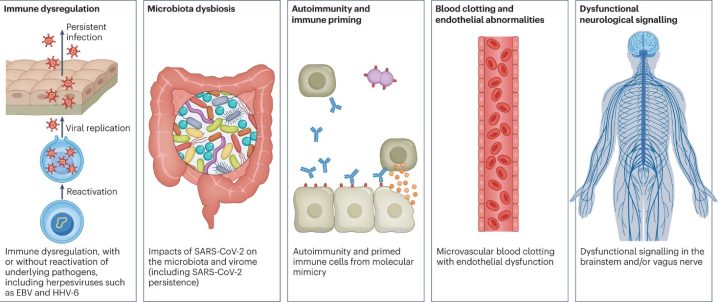

Although studies have found evidence of long COVID, we know little about the causes behind the condition. A recent systematic literature review in the Lancet found that 45 % of people of COVID-19 survivors were experiencing unresolved symptoms at four months. Interestingly, vaccination seemed to protect against the condition. Currently, researchers are studying five main hypothetical mechanisms for long COVID:

- Immune dysregulation: the immune system is too active and is causing damage to surrounding tissues. The activation could be due to the direct effect of the virus on the T helper cells, the conductors of the immune system. Another speculation is the recurrence of underlying viral infections, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6).

- Gut dysbiosis: After COVID-19, the gut’s normal flora changes drastically. Specific bacteria in the gut strongly correlate to long-term symptoms. Moreover, researchers have found SARS-CoV-2 in the stool samples for up to seven months after the infection.

- Autoimmunity: Our immune system recognizes various targets – sometimes our own. Ordinarily, the immune system eliminates the cells that harm our tissues. However, sometimes a microbe resembling the structure of our tissue can activate normal immune cells to attack us. Many studies have found elevated levels of autoantibodies in long COVID patients. However, they are not a significant component in explaining long COVID.

- Blood clotting and damage to the blood vessels: In addition to respiratory illness, SARS-CoV-2 can cause damage to many organ systems. The damage is usually caused by immune cells fighting against the virus rather than the direct infection of the virus itself. Inflammation of the blood vessels and activation of platelets increases the risk of blood clotting causing direct tissue damage.

- Dysfunctional neurological signaling: Studies have found that people suffering from neurological symptoms of long COVID have findings indicating inflammation of the brain and nerves. Additionally, metabolic pathways in long COVID patients are similar to patients with dementia, multiple sclerosis, and psychiatric disorders.

At University of Turku, we are currently testing the first hypothetical mechanism of long COVID. We have followed up 74 patients recovering from COVID-19 for two years. During this time, we have collected their medical history and self-reporting of symptoms. In addition, we have done X-ray imaging and physical examination in the follow-ups. We have divided these patients into healthy controls and those with long-term symptoms that any other underlying condition cannot explain.

Next, we will analyze various inflammatory markers from the blood samples collected at multiple time points during this 24-month follow-up. Hopefully, we will find part of the explanation for this unusual phenomenon and be a step closer to finding better predictive tools and treatments for long COVID.

Antti Hurme

The writer is a doctoral researcher at the Institute of Biomedicine.

Sources:

- O’Mahoney, Lauren L et al. “The prevalence and long-term health effects of Long Covid among hospitalised and non-hospitalised populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” EClinicalMedicine vol. 55 101762. 1 Dec. 2022, doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101762

- Davis, Hannah E et al. “Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations.” Nature reviews. Microbiology vol. 21,3 (2023): 133-146. doi:10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2

- Glynne, Paul et al. “Long COVID following mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: characteristic T cell alterations and response to antihistamines.” Journal of investigative medicine : the official publication of the American Federation for Clinical Research vol. 70,1 (2022): 61-67. doi:10.1136/jim-2021-002051

- Phetsouphanh, Chansavath et al. “Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection.” Nature immunology vol. 23,2 (2022): 210-216. doi:10.1038/s41590-021-01113-x

- Liu, Qin et al. “Gut microbiota dynamics in a prospective cohort of patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome.” Gut vol. 71,3 (2022): 544-552. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325989

- Wallukat, Gerd et al. “Functional autoantibodies against G-protein coupled receptors in patients with persistent Long-COVID-19 symptoms.” Journal of translational autoimmunity vol. 4 (2021): 100100. doi:10.1016/j.jtauto.2021.100100

- Pretorius, Etheresia et al. “Persistent clotting protein pathology in Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin.” Cardiovascular diabetology vol. 20,1 172. 23 Aug. 2021, doi:10.1186/s12933-021-01359-7

- Cysique, L. A. et al. Post-acute COVID-19 cognitive impairment and decline uniquely associate with kynurenine pathway activation: a longitudinal observational study. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.07.22276020

- Reiken, Steve et al. “Alzheimer’s-like signaling in brains of COVID-19 patients.” Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association vol. 18,5 (2022): 955-965. doi:10.1002/alz.12558