Temporal imagination: language, self, and metaphor

Have you ever wondered if we can turn back time?

From a language perspective, the answer is a resounding yes! We can manipulate time, moving it forward or backward along different temporal axes, without being confused. It’s like playing with timelines, except instead of a sci-fi movie, it’s happening right in our conversations.

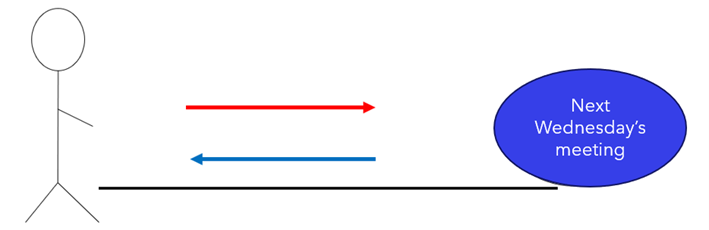

Let’s start with a small thought experiment. Imagine you have a meeting scheduled for next Wednesday, and someone tells you it’s been moved forward by two days. Wait, what day is the new meeting?

If you said Monday, you’re picturing time moving toward you. But if you said Friday, you’re taking an active role in moving the meeting away from you. That is to say, in this second scenario you imagine yourself moving and imagine time moving in the same direction.

This small example has been in use for a long time as a psychological test to prompt people’s perspectives of time. This example also shows that we imagine the passage of time using physical motion through space. That is to say, when we talk about the passage of time, we’re actually drawing on our experiences of moving through space.

The reason why we imagine time through motion is that we do not directly perceive time in the same tangible way as space, so we use our experiences of spatial movement as a metaphorical framework. For instance, an expression like We are approaching summer, invokes motion along a time path, and we metaphorically head towards the sunny season just like we would in a car, head towards a destination. Interestingly, this discovery of this metaphor suggests that a person who has never experienced motion through space is likely not to comprehend the passage of time!

In my doctoral project, I dive deep into the mysteries of time, language, and cognition for speakers of Arabic and English. I explore questions such as: How do speakers of Arabic and English use the same metaphor of time?

Through my research and by analyzing over 2000 expressions of metaphors, I’ve discovered that we navigate this mental maze of space, motion, and time by performing a unique pattern of mental calculation, but don’t worry, we don’t need a calculator. Our brain does it automatically! Whether we’re discussing the past, present, or future, our minds are constantly calculating our position relative to the moment of speech and to the events being described.

This ability develops as we grow; we are not born with it. Consider trying to explain the concept of the future to a one-year-old, or even the duration of a single hour! Unfortunately, as we age, this ability is at risk of diminishing, particularly with conditions like dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Amidst this linguistic exploration, I also distinguish between two personas in the discourse of time: the speaker persona, anchored in the speech event, and the experiencer persona, imagined by the speaker with their own distinct temporal references. You can think of the experiencer as an imaginary character that we use to be able to go back in time or to understand narratives and fictional scenarios. This ability to have different conceptions of the self facilitates temporal imagination.

Consider for instance the example We are going through summer. In this example, the speaker and the experiencer agree in their references to the present moment. Now let’s tweak the tense and consider We were going through summer. Here, the experiencer and the speaker disagree in terms of their temporal references: the experiencer’s imagined ‘now’ is in the speaker’s real past. This shift effectively transports us back in time and creates a dual conceptualization of the self: summer is vividly present for the imagined experiencer, influenced by the meaning of the verb expression go through, while it is relegated to the past for the speaker due to the past tense.

While this explanation may seem technical, we encounter numerous variations of speaker and experiencer references daily and comprehend them effortlessly. In my doctoral monograph, I describe 44 different temporal combinations of conjugated verbs: 20 in Arabic and 24 in English. For each of these verbs, I carefully discuss the speaker and experiencer references and I illustrate our mental representations of each temporal scenario using cognitive linguistic models.

Although I do not have the space to share all the findings of my project, it suffices to retain the following: The next time you find yourself lost in thought about time, remember that you’re not just talking about minutes and hours – you’re exploring the very fabric of human experience and cognition. And who knows? Maybe one day we’ll unlock the secrets of time travel, beyond the language we speak every day.

Asma Dhifallah

I am a multilingual researcher specializing in Cognitive Linguistics, with several years of experience in language and writing instruction, in addition to academic research. My work relates to the connections between language and the mind, and the development and analysis of language corpora. My approach combines quantitative and qualitative methodologies, with a particular focus on combining theoretical descriptions with statistical modeling techniques.

References to my doctoral dissertation:

ISSN 0082-6987 (Print)

ISSN 2343-3191 (Online)

ISBN 978-951-29-9768-8 (PRINT)

ISBN 978-951-29-9769-5 (PDF)

Image: Daniele Levis Pelusi