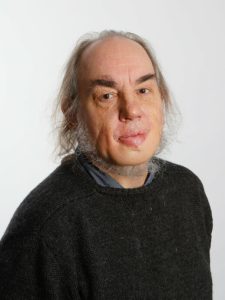

Martin Cloonan

Director, Turku Institute for Advanced Studies

So, I’ve got a new book out. It’s called Made in Scotland and I co-edited it with my good friends and colleagues Simon Frith and John Williamson. You can get it on Amazon and other places. But why, dear reader, should you care?

Well, first of all it’s about music. You know, that thing we take for granted as just being there. In fact, it’s there at nearly all of the major events of our lives. Weddings, funerals, christenings, social gatherings of all sorts. At all these events we have music. To me, that makes music somehow special. We don’t generally watch films or plays or look at art on the occasions I’ve just noted, but we do have music. So, think about that.

Second, this is about music in Scotland. Why should that matter? Because Scotland is different. It’s a country which is within another country – the United Kingdom. Whether that arrangement continues time will tell, but while it does it has certain consequences. Made in Scotland is part of a series of books on music entitled Made in X. This has included books on Finland, Australia, Greece and Taiwan. The point of such books is to move the study of popular music away from an Anglo-US hegemony and towards places which might otherwise be seen as peripheral. All of the aforementioned books are about nation-states. Scotland is a nation, but not a state. This means that making music there is different as matters which affect musicians such as broadcasting, copyright, minimum legislation and immigrations are legislated for somewhere else – London. In this sense to be Made in Scotland is to be made somewhere different.

Scotland is also simultaneously part of and apart from the Anglo-US hegemony. Its artists generally perform in English and have access to all the benefits provided by the UK being one of the world’s most important places for the production and consumption of popular music. UK-produced music is internationally successful and Scottish artists have been part of that success. So in this sense music made in Scotland is part of the prevailing hegemony. However, to remain in Scotland is to be outside the UK “norm” of being in and around London – the location of the major record companies, live music promoters, broadcasters, copyright organisations etc. Scottish artists need access to such things and so need to cross the border in order to succeed. Very few artists can make a living on working in Scotland alone. While such internationalism is, of course, true of many musicians, Scotland gives it a particular flavor.

So, what is in the book? I’m glad you asked. Having three editors meant that we ended up having three sections: Histories (edited by John Williamson), Politics and Policies (me) and Future and Imaginings (edited by Simon Frith). We did not try to be comprehensive (one potential reviewer has already bemoaned the lack of reggae in the book), but are hopefully illustrative. We cover broadcasting, live music, record labels, jazz, girl groups, festivals, Gaelic music, musical heritage, music education, representations of Scottishness, hip-hop, the use of music to promote Scottish nationalism and the interaction of Scottish music and fiction. In all these areas the distinctiveness of music production and reception in Scotland is evidenced

Are the topics we cover enough? Quite possibly not. There is no country music (which is huge in Glasgow and its environs), not much on music by the country’s ethnic minorities, nothing on contemporary art music, no sonic art and only two references to Calvin Harris. What were we thinking? Well, what we were thinking is who do we know and who can we convince to write something for the usual academic fee of precisely nothing? We tried to be diverse, but maybe not diverse enough for some people. Moreover, we wanted this “academic” book to include the voices of musicians and those within the Scottish music industries. So, interspersed with academic analysis there are interviews with musicians and promoters (but none with Scottish record labels). We end the book with the thoughts of some within the Scottish music industries on the future of music in Scotland.

Of course, we hope that the book will become a standard text on popular music degree programmes in Scotland and beyond. Like all authors, we want to be read. But more importantly, we want it to change people’s perceptions both of Scotland and of the music made there. We do want it to challenge the Anglo-US hegemony. For me personally, this is another instance where I point out what is missing or overlooked in popular music studies. I have previously charted the untold story of censorship in UK music, examined music policy, published on the use of music in violence and spearheaded a movement which has moved the study of popular music on from examining recorded music to a consideration of live music. In all this my work has tried to fill in some missing gaps. I have said “Hang on a minute, there is something missing here” – then found it and explained it. It’s been a blast.

In this respect Made in Scotland is a statement. Its very existence means that we are claiming that there is something worth knowing about how music is produced and consumed in the country. There have been previous studies of music in Scotland, but this is the first academic collection. Popular music is now a global force, but Made in Scotland reminds us that how that music is produced and how we experience it is affected by place. There is something unique in the Scottish experience of music – of its production and reception.

If you’ve read this far, you should read the book. Hopefully it will change the way you think. That’s all we’re trying to do.