I was recently asked to do a remote lecture on Louis Hjelmslev’s work. I accepted. It was mainly on the ‘Prolegomena to a Theory of Language’, mixed with ‘Structural Analysis of Language’ and ‘La stratification du langage’. I won’t comment on that lecture, considering it’s already in the past. Instead, what I want to do is to expand on that lecture, to further elaborate what is known as Hjelmslev’s net and what he, later on, came to refer to as the stratification of language or, should I say, just stratification, of just about everything.

The problem with Hjelmslev’s work is that it’s fragmented, bits of it being published in this and/or that language. It is also super dense. Now, don’t get me wrong, I like complexity and complex conceptual frameworks. The problem is rather that his key works are rather short, so he doesn’t really end up fleshing out his concepts. For example, he introduces concept after concept, some of which he later on abandons in favor of other concepts. I can see why he does that, but I don’t think it’s the best way to go about it. To be fair, I can’t blame him for doing what he set out to do. I don’t think he introduces too many concepts, but rather that he doesn’t spend much time elaborating them.

As this is going to be a quite a slog (believe me!) and there’s going to be a lot of concepts that will be discussed (but’s that’s logical rigor!), I’ll provide you with a cheat sheet. I won’t italicize the concepts here, unlike in the text, because otherwise I’d be italicizing the whole cheat sheet. I’ve abbreviated Gilles Deleuze as D, Félix Guattari as G, and Deleuze and Guattari as D&G. I’ve simplified some things in it, so if something is off, it’s because I didn’t want to go on and on about each concept. That would have been counterproductive.

Cheat sheet

Purport = matter, meaning, matter-meaning (D&G, G), sense (D), plane of consistency/immanence/composition (D&G), body without organs (D&G), metastratum (D&G), substance (Spinoza)

Substance = formed matter (D&G), epistratum (D&G), flow (G)

Form = parastratum (D&G), code (G)

Manifestation = the relation between formed matter and form, matter appearing as formed matter in relation to form

Planes = attributes (Spinoza)

Content = signified (Saussure), first articulation (D&G), variable functive of a function of stratification (D&G)

Expression = signifier (Saussure), second articulation (D&G), variable functive of a function of stratification (D&G)

Form of content = non-discursive formation (Foucault), form of the visible (D), visibilities (D)

Form of expression = discursive formation (Foucault), form of the articulable (D), statements (D)

Solidarity = the relation between content and expression that makes them appear always at the same time (Hjelmslev), reciprocal presupposition (D&G)

Isomorphism = identical form, relationally the same

Correspondence = conformity, realized as the same

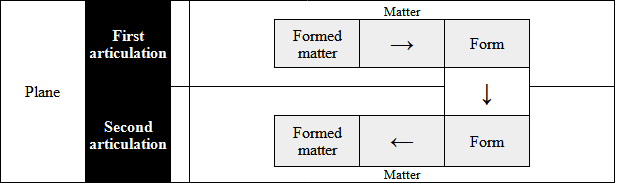

Double articulation = double distinction, two articulations, first content, then expression (Martinet, D&G), both articulations are in themselves double (D&G)

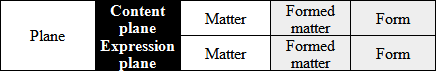

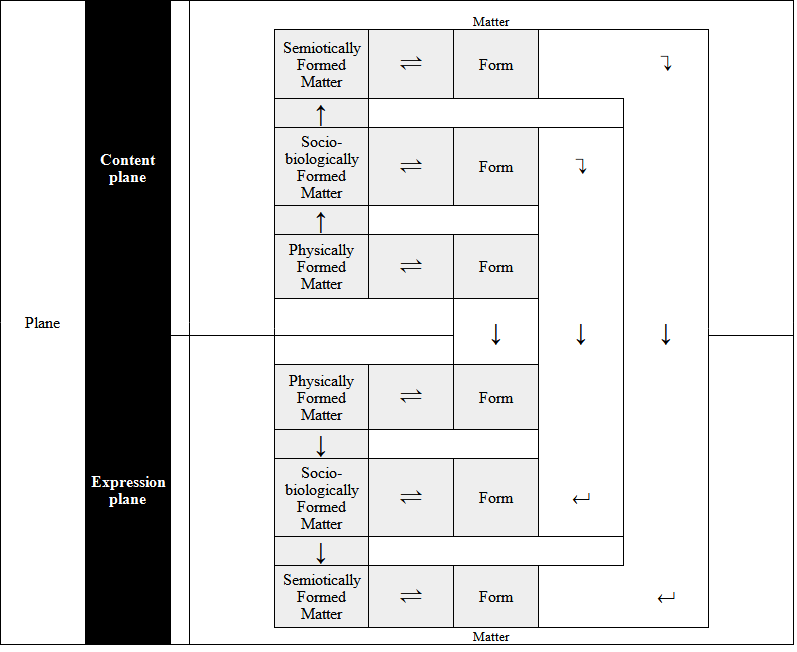

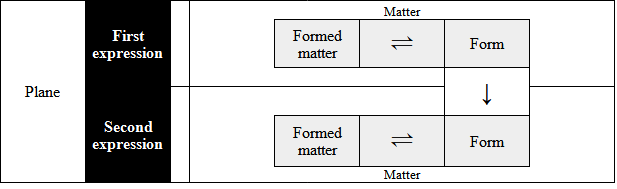

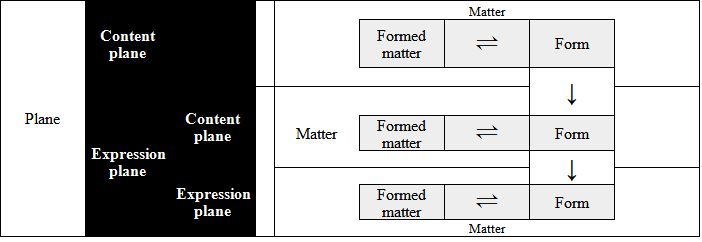

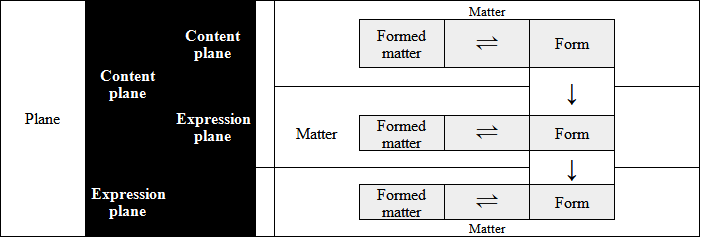

Hjelmslev’s net = stratification of purport (Hjelmslev), stratification of matter-meaning (D&G), consists of two planes (content and expression) that both have substance (formed matter) and form, resulting in substance (formed matter) of content, form of content, form of expression and substance (formed matter) of expression (Hjelmslev)

Stratum = layer (Hjelmslev), panels of Hjelmslev’s net, substance of content, form of content, form of expression and substance of expression (G), historical formation (D)

Level = stratum on stratum, layer on layer (D&G)

Metastratum = the connection between the strata, i.e., formed matter and form, and matter/plane (D&G)

Interstratum = what is between the strata (D&G), assemblage (D&G)

Substratum = the stratum below a stratum, the layer below a layer (D&G), serves the stratum as its exterior milieu or medium, but not exterior to that stratum as strata or layers always come at least in pairs (D&G)

Epistratum = the stratum on top of a stratum (D&G)

Parastratum = the stratum next to a stratum (D&G)

Epistratum/parastratum = strata considered vertically/horizontally (D&G), shatter the continuity of an idealized stratum, permitting the formation of different formed matter/forms (D&G)

Physical level = non-semiotic level, inorganic stratum, the non-living, a formal distiction between content and expression (D&G)

Socio-biological level = non-semiotic level, organic stratum, the living, homoplastic, capable of divergence, real distiction between content and expression, relative autonomy of expression from content (D&G)

Level of collective appreciation = semiotic level, anthropomorphic stratum, humans, alloplastic, the autonomy of expression from content is further expanded, capable of acting on the other levels/strata (D&G)

Signs and non-signs

Anyway, what is interesting about Hjelmslev’s work is his relational and functional approach. The gist of that is that parts functions as parts of a whole, which, in turn, functions as a part of another whole alongside other parts. This is not a unique to him, even though it might be unique to him in linguistics. You’ll find a much better explanation of how parts and wholes function in Baruch Spinoza’s ‘Ethics’. That said, I realize that comparing Hjelmslev to Spinoza is unfair, considering that comparing anyone to Spinoza is unfair.

Hjelmslev also has this “insane meaning theory” that everything else is based on, as pointed out by Félix Guattari (208) in ‘Hjelmslev and Immanence’. The insanity of it is that meaning does not reside in language, as such. Meaning is tied to the sign, yes, but it is not the sign itself. Instead, when we take a closer look at language, how it works, it appears to us that the meaning that we make through signs, and only through signs, is based on non-signs, what Hjelmslev (29) refers to as figuræ (figurae, figures) in ‘Prolegomena’. In his (29) words:

“A language is by its aim first and foremost a sign system; in order to be fully adequate it must always be ready to form new signs, new words or new roots.”

This is evident from how languages keep changing, how what people used to say back in the day, whenever that was, is no longer the same as it is now. Of course, the further back you go, the more likely it is that things have changed, so that what people said yesterday isn’t that different from what they say today. Anyway, his point simply is that a sign system must be adaptive. He (29) continues:

“But, with all its limitless abundance, in order to be fully adequate, a language must likewise be easy to manage, practice in acquisition and use.”

This explains why things don’t change that much and how, oddly enough, we keep repeating the same stuff, over and over again, instead of coming up with something new all the time, despite the limitless potential. He (29) continues:

“Under the requirement of an unrestricted number of signs, this can be achieved by all the signs’ being constructed of non-signs whose number is restricted, and, preferably, severely restricted.”

Here we move from signs to non-signs, to the figuræ (figures). He (29) elaborates the role of these non-signs in sign systems:

“Thus, a language is so ordered that with the help of a handful of figuræ and through ever new arrangements of them a legion of signs can be constructed.”

Simply put, you get signs from non-signs, meaning from non-meaning, sense from nonsense, which is pretty insane, well, for a linguist, as explained by Guattari (207-209). Hjelmslev (29) summarizes how sign systems, such as a language functions:

“We thus have every reason to suppose that in this feature – the construction of the sign from a restricted number of figuræ – we have found an essential basic feature in the structure of any language.”

Guattari (207) paraphrases this:

“What defines language is not signification, but its capacity for reproducing an infinity (a flow) of signs, given a finite (axiomatic) figure machine.”

So, oddly enough, what is remarkable about an actual sign system, such as a language, is that it is never a mere sign system, a pure sign system. It is rather a system of non-signs, a system of figuræ, that operates to create signs, as Hjelmslev (29) goes on to explain:

“Languages, then, cannot be described as pure sign systems. By the aim usually attributed to them they are first and foremost sign systems; but by their internal structure they are first and foremost something different, namely systems of figuræ that can be used to construct signs.”

This is why he (29) insists that defining a language as a sign system is unsatisfactory. For him (29), signs are therefore external functions, whereas the figuræ are internal functions. What I like about his (27) definitions is that he never slips to saying that sign is the meaning, but rather argues that sign is meaningful, a bearer of meaning, when it is defined by a function, in contradistinction to a non-sign. What is important here is how we get something, something meaningful, something sensical, from what amounts to, well, nothing, nothing meaningful, nothing sensical. I would say that this is why Guattari (208) thinks that Hjelmslev’s meaning theory is enough to make linguists go insane. Then again, there is more to this, why it’s such an insane theory for the linguists, but we’ll get to that shortly. Part of that is the emphasis on function, which we’ll return to in just a minute.

Functives: content and expression

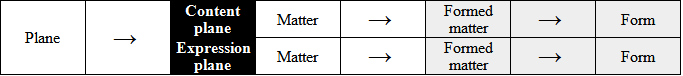

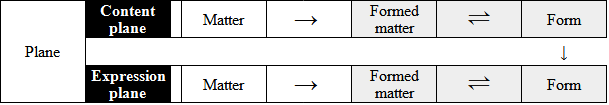

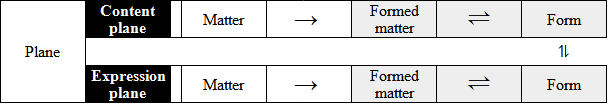

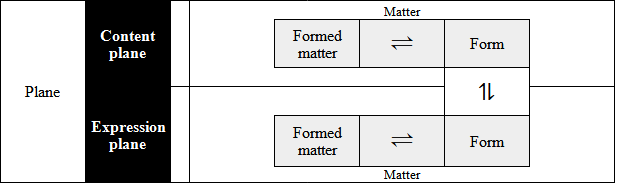

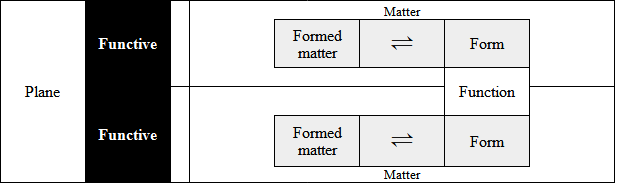

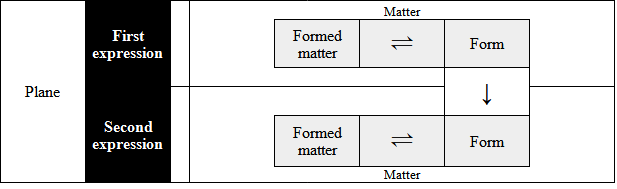

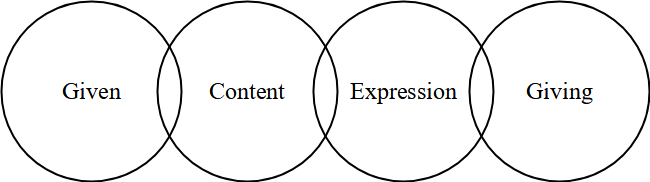

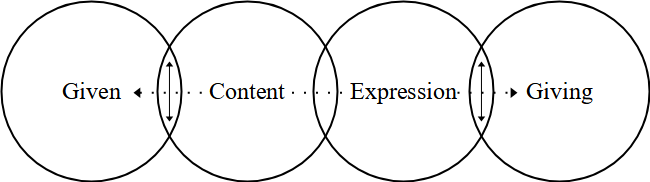

What I find particularly interesting about Hjelmslev’s relational and functional approach is what later on became known as his net. Hjemslev (35-36) explains this in the ‘Prolegomena’:

“By virtue of the sign function and only by virtue of it, exists its two functives, which can now be precisely designated as the content-form and the expression-form. And by virtue of the content-form and the expression-form, and only by virtue of them, exists respectively the content-substance and the expression-substance, which appear by the form’s being projected on to the purport, just as an open net casts its shadow down on an undivided surface.”

To make more sense of this, we must lock on to a number of key concepts: content and expression, substance and form, and purport. For him (29-30), content and expression are functives. They are entities connected to one another as terminals through sign function or, in short, function. They are virtually the same, but not actually same. What I mean by this is that they are the same, but they are not the same, inasmuch as they enter into relationship with one another as terminals, i.e., when they function in relation to one another. In his (30) words:

“[A] function is inconceivable without its terminals, and the terminals are only end points for the function and are thus inconceivable without it.”

He (37-38) goes as far as to say that there is no reason to refer to functives as content and expression, as you could just say that there are these functions, that exist between terminals, between entities. He (37) indicates that he uses content and expression out of habit, having chosen them “in conformity with established notions”, and thus using them is “quite arbitrary.” I can see why he would do that, why he opts to refer to functives as content and expression. It’s just easier to comprehend at a glance.

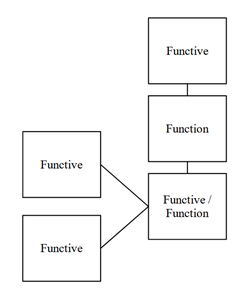

To be clear, he (20) defines function as something is in between a whole and its parts, what he refers to as a class and its segments. He (20) adds to this that the terminals of the function are the functives. If terminal seem odd to you, think of the word as a point of connection, like in electric circuits or at transportation nodes, such as bus stations, railway stations, seaports, or airports. A functive is a fancy way of saying “an object that has function to other objects”, as he (20) points out. To complicate this a bit, a function can also be a functive, if there is a function between functions. He (20) mentions this to distinguish between two types of functives, those that are functions of functions, and those that are not functions of functions, what he refers to as entities, which, in turn, is just another word for a terminal, “an object that has function to other objects.”

I don’t know about you, but I’d say that he opted to make use of the established notions, content and expression, not because he needed to do so, out of respect for others in his field or fields, but because the functive as function of a function or as a terminal or entity is pretty confusing at a glance. I had to take a moment to get through that bit, to make sense of it, so, yeah, it must have made sense to him to opt for the established notions. I guess you could make it work, as you’ll see soon enough, but it’s just unwieldy.

Deleuze and Guattari (511) comment on this in ‘A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia’, noting that content and expression are simply two functives of a function. That is also why Guattari (204) states in ‘Hjelmslev and Immanence’ that you might as well call them A and B. Content and expression are just a “pseudo-dualism”, as he (204) points out. For him (204), the problem is Hjelmslev’s loyalty to linguistics, paying homage to “Papa Saussure”, while clearly seeking to go beyond linguistics. You can see this already in the ‘Prolegomena’. He starts with linguistics, only to go beyond it, ending up with semiotics.

Hjemslev (30) goes on to specify that content and expression are tied to the sign function or, in short, function, appearing only in solidarity, only if the function is there. To be more specific, as he (30) points out, the sign function or, in short, function “is in itself a solidarity”, whereas these two entities, these two terminals, are solidary, always presupposing one another, which is why they never appear in isolation, why they make no sense on their own. In his (30) words:

“An expression is expression only by virtue of being an expression of a content, and a content is content only by virtue of being a content of an expression.”

And, to be clear, as he (30) goes on to emphasize:

“[T]here can be no content without an expression, or expressionless content; neither can there be an expression without a content, or content[]less expression.”

He (30) exemplifies this with how a thought can be thought but it is not a linguistic content without that thought being expressed, one way or another. Conversely, if we just make random sounds without giving any of it any thought, there is something being expressed, but the expression is not a linguistic expression, considering that it lacks the linguistic content for it to be linguistic expression.

Hylomorphism

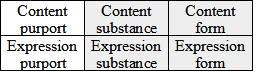

Before I move on, I think it is worth clarifying a couple of terms used by Ferdinand de Saussure. Why? Well, while they are not used by Hjelmslev, they help us to understand why they are not used. Saussure (111-113) relies on a distinction between matter/substance and form in his ‘Course in General Linguistics’. For him (112), there is, on one hand, “the indefinite plane of jumbled ideas” and, on the other hand, “the equally vague plane of sounds”. That’s what he means by matter or substance. If you ask me, the problem with Saussure is that he isn’t too specific about this, considering that he appears to be using matter or substance synonymously. It is then segmented according to a form that is produced at the borderland between the two planes, as clarified by him (112-113). He (112) visualizes this with a diagram depicting the surface of a body of water, providing a top-down view of it, with ripples forming on its surface caused changes in atmospheric pressure (better known as wind), dividing it into a number of waves. In summary, we get something like this once we add the signifier and signified to the mix as well (I):

| Substance | Form | |

| Signified (content) | indefinite plane of jumbled ideas shapeless thought mass | definite plane of ideas conceptual order |

| Signifier (expression) | indefinite plane of sounds shapeless sound mass | definite plane of sounds sound order |

The problem with this type of duality is that it is hylomorphic. What is hylomorphism? To give you the short answer, it is how matter takes form. The long answer goes back to Aristotle. He (133) explains this in his ‘Physics’, noting that matter is “that out of which” something is made. He (133) uses the example of how syllables are made out of letters. Conversely, form is therefore that which organizes the matter, or, rather the organization of the matter.

Deleuze and Guattari (369, 408) address hylomorphism in ‘A Thousand Plateaus’. For them (363), it is a model that implies “both a form that organizes matter and a matter prepared for the form”. In its simplest form (no pun intended), hylomorphism results in what I’d call naïve realism, in reducing matter into content (things) and form into expression (words), as Deleuze and Guattari (369) point out. That’s, however, not a real concern here as both Saussure and Hjelmslev are opposed to such views. For Deleuze and Guattari (408), there are two problems with hylomorphism. Firstly, matter is deemed to be homogeneous. Secondly, form is considered to be fixed.

I can’t be entirely sure whether Saussure’s matter or substance is homogeneous, considering that he (112-113) doesn’t comment on it. Then again, he (112-113) does mention that he is dealing “two shapeless masses” and the examples he provides, a sheet of water and a sheet of paper, do make you think of something that is considered to be homogeneous. Moreover, he (15) does consider language (langue) to be homogeneous, which does suggest that. Then again, he (15) notes that speech is heterogeneous, which goes against that. Therefore, I’d say this has more to do with the second problem, how form is considered to be fixed.

While I’m a bit uncertain about the homogeneity, the issue of fixity is certainly something that undermines Saussure as he couldn’t care less about language as an everyday thing. He (13-14) is certainly aware of it, that it is a “social product”, considering that he acknowledges how it is, on one hand, something that individuals do, or, as he puts it, execute, and, on the other hand, shared by individuals, so that language is never simply individual but collective. That said, his definition of language as social or collective is not exactly what I’d call social or collective as, for him (14), speech (parole) is merely individual, consisting of willful and intellectual acts that the person expressing something chooses to express. In his (14) words, “[t]he speaker uses the language code for expressing his own thought”, while “the psychophysical mechanism … allows him to exteriorize these combinations.” In other words, for him (14) language is something that all humans have, at least potentially, assuming that one is part of a social group. He (14-15) bases his definition of language and the study of language, what we’d call linguistics, what he calls semiology, on “the heterogeneous mass of speech facts”, but quickly dispenses with it and its heterogeneity in favor viewing language of a storehouse of homogenous linguistics facts. He ends up treating form as “[a]n invariable form” and matter “a variable matter of the invariant”, “extracting constants from variables”, as explained by Deleuze and Guattari (369). This is an odd move, considering that his starting point is speech, heterogeneous and variable.

That’s odd because he moves to assert that language is homogeneous and invariable, which then, somehow, allows him to treat all that everyday heterogeneity and variation as mere deviation from a standard. The problem here is that the supposed homogeneity, invariance and universality of language is based on the heterogeneity, variation and particularity or singularity. In other words, the problem with this is that it is taken for granted that there is a constant or an invariant, instead of constant or continuous variation. I’d say that it’s not that there aren’t generalities, regularities or tendencies, as there are, but they are just that, something that is now common, for whatever reason that may be, but might not have been common in the past nor be common in the future.

This is issue also undermines Hjelmslev, albeit, I’d say it has less to do with his formulations than it has to do with his unwillingness to address the issue. He (100-101) is explicit about this, noting in ‘Structural Analysis of Language’, that as far as he is concerned, he sides with Saussure, focusing solely on the form, so as to take what Saussure started to its logical conclusion. He (188) also comments on this in ‘La stratification du langage’, noting that speech is just that which is arbitrary in language, how certain strata meet one another in this and/or that relationship with one another. In other words, he isn’t or doesn’t appear to be too keen on speech because it is arbitrary. So, he’d rather focus on language as a system of stabilized connections between variants in usage on certain strata or, more simply put, between linguistic or semiotic acts, and the standards that act as the sets of these possible stabilized connections, as he (188) points out.

I think he could have addressed it as his formulations give way more room to do so than Saussure’s formulations, but he just didn’t. I think he was reluctant to do so because it just wasn’t something that people did as pragmatics was hardly a thing back then. Of course, that’s still on him, just as it is on Saussure. Anyway, when it comes to hylomorphism, Hjelmslev fares better than Saussure in this regard. This is because even though his formulation is also plagued by its fixity, he doesn’t rely on the Aristotelian opposition between matter and form.

A moment of candor

While it may seem like I’m just against Saussure, looking give him a bad rap, there are some things that I like about his work. For example, while I might not agree with his views, as I am for sure against structuralism (in the form that it is generally understood), I can appreciate the fact that he went against the tide, basically saying ‘fuck it’, ‘fuck y’all’, I know you guys like to keep doing more of the same, but ‘fuck your semantics’, ‘fuck your phonetics’ and ‘fuck your philology’, ‘yolo’, I’m after something with this and I’ll do it no matter what you, the old guard, think of it, because it’s not like you are going to support something that will, in all likelihood, relegate you and your work as subordinate to my (his) work, as noted by Hjelmslev (97-98, 100) in ‘Structural Analysis of Language’, albeit in a less colloquial manner. This is also Hjelmslev’s view, albeit, again, he explains that in less colloquial manner than I just did (for the sake of emphasis, and to make this less of slog for you to read, believe me!), and, well, he isn’t afraid to express it, which probably didn’t make him any friends. He (2) starts kicking doors down right in the beginning of his ‘Prolegomena’ by going after semantics, phonetics, and philology for their lack of structure, for being content of being merely descriptive and for their “zealous haste” to accumulate knowledge, you know, for just doing more of the same in a disconnected manner, bearing relevance to ‘fuck all’ as I might express it to grab your attention.

To be candid, to speak freely, as a parrhesiastes, I can’t stand linguistics as it is, stuffy, boring, irrelevant and disconnected from everyday life, while also pretentious, acting, as if it wasn’t all that. If you think that structuralism, what Saussure or Hjelmslev discuss, is boring, which it is, and disconnected from everyday life, which it is, do not engage in morphology, phonetics, phonology, semantics, or syntax, you know, the cornerstones of linguistics, unless you are really into institutional sclerosis. Then there’s the disingenuity of all that, the underhandedness of it, just doing more of the same, despite the presuppositions that just don’t hold or, rather, could hold, assuming that you could make them hold, which I doubt.

For example, when you have something like second language acquisition (SLA or L2), I can see what the point is, there being a logic to it, practical value and applicability, fair enough, but all of that builds on the presuppositions that languages exist, that this and/or that language exists as a given, a priori, and that the first language you acquire from other people becomes your native language, which, in turn becomes the invariant that functions as the standard against which the supposed non-native speakers are to be judged in terms of their competence as they try to learn that language. Now, to be clear, I believe that languages do exist, don’t get me wrong, but what I don’t believe is that they exist, on their own, as given, a priori. Instead, they exist as political entities. So, the issue I take with most of linguistics, including structuralism, as well as SLA or L2, is that there is this reliance on presuppositions that just don’t hold once you hold them up to close scrutiny. I just don’t get it how people can keep on doing more of the same if they are made aware of the issue, that what is supposed to keep it all together just doesn’t hold. I don’t know about you, but I sure rethink things if I realize that whatever I’m dealing with just doesn’t make any sense. I don’t mind having been wrong or inconsistent about something. It happens. No one is perfect. I acknowledge that and move on. It’s okay to change your mind. I do that all the time.

Deleuze and Guattari (75) do an excellent job explaining this in ‘A Thousand Plateaus’, how linguistics, as a field or a discipline, fails to keep itself in check as it has these presuppositions. They (75-76) explain this through an example, which bears direct relevance to language learning:

“When the [teacher] instructs [the] students on a rule of grammar …, [the teacher] is not informing them, any more than [he or] she is informing [him- or] herself when she questions a student. [He or s]he does not so much instruct as ‘insign,’ give orders or commands. A teacher’s commands are not external or additional to what he or she teaches us. They do not flow from primary significations or result from information: an order always and already concerns prior orders, which is why ordering is redundancy. The compulsory education machine does not communicate information; it imposes upon the child semiotic coordinates possessing all of the dual foundations of grammar (masculine-feminine, singular-plural, noun-verb, subject of the statement-subject of enunciation, etc.)”

Exactly! To paraphrase this, to get to the gist of this, language is not about communicating information between people, but about making sure that people know their place. Okay, it is also about communicating information, but only in the sense that there has to be information that is successfully emitted or transmitted for it be observed, as they (76) point out. That said, that’s not all there is to it, which is why they (76) state that:

“Language is made not to be believed but to be obeyed, and to compel obedience.”

And that (76):

“Words are not tools, but we give children language, pens, and notebooks as we give workers shovels and pickaxes.”

As well as (76):

“A rule of grammar is a power marker before it is a syntactical marker.”

So, for example, when one studies how students learn language, how they fare, how supposedly competent they are in a certain language at a certain age or level of education, one presupposes that there is such a thing as linguistic competence, which, in turn, presupposes that there is this language, that it is like this, and that one must adhere to it. In other words, one presupposes that there is a given standard and that the students are to adhere to this standard.

While the intention might be good, to promote language learning, the problem with this is that it reinforces this conception of language and native speaker competence. I’d be fine with this kind of research if the researchers were honest enough to mention that what they are studying and how they are studying it is based on certain presuppositions. The point I’m making here is that there are these presuppositions and, to be frank, they don’t look too good. There’s no hiding behind them. Well, okay, you can hide behind them, you can keep ignoring the issue, but that’s just that, you are now deciding to do that. Also, by willfully ignoring the issue you are making it apparent that you are doing it because it suits you, because you’ve managed to convince the funding agencies, both private and public, that your research is needed. Needed for what? To indicate that students achieve a certain linguistic competence, which is, conveniently, defined by the researchers themselves (and their predecessors, like in an apostolic succession to maintain orthodoxy), so that you can keep your job. It also serves both private and public interests, reinforcing state language policies and private education business, so it’s no like there’s going to be a shortage of money for that.

Now, I’m not fond of criticizing others without giving them any credit and/or explaining what it is that they could do to fix the issues that I’m trying to make them aware of. So, what could the researchers do? Well, instead of drinking the kool-aid, they could point out that they are, in fact, interested in looking at how teachers impose upon the students in this way, as expected of them by their superiors, and how the students come to acquire not only a language, as judged according to a certain standard, a certain constant extracted from a number of variants, but also this view that treats that constant extracted from the variants as a given.

The problem isn’t that researchers study languages, but rather that they take them for granted. Instead of looking at what this or that standard language consists of and how it is defined, for example, in terms of grammar, we should be asking who gets to define that, whose interests it serves and, conversely, who do not get to have a say and whose interests it does not serve or even goes against.

Now, of course, when we shift from what to who, we are not trying to find this and/or that person responsible for that. We are not interested in blaming this and/or that researcher or this and/or that teacher for doing and/or saying this and/or that, but rather investigating what makes them do and/or say what they do and/or say, what makes them express what they express. I don’t know about you, but I couldn’t care less about the people involved, nor their views on why they do and/or say what do and/or say. What interests me is what makes those people do and/or say what do and/or say. It might be interesting to assess people’s views, what they think motivates them do and/or say whatever it is that they do and/or say, not because I’d take their word for it, but because it’d be interesting to assess what it is or might be that makes them explain their own actions in this and/or that way.

Anyway, be that, all that, as it may, I agree with Michel Foucault on this issue, how the researcher, what he refers to as the intellectual, should never seek to speak for others, to tell how tell how things are, followed by telling how they ought to be, as if it was their responsibility to do so, as they “are themselves agents of this system of power” that “blocks, prohibits, and invalidates” people’s access to knowledge, not by the means of censorship but by “subtly penetrat[ing] an entire societal network”, as expressed by him (207) in conversation with Deleuze in ‘Intellectuals and Power’. In other words, when we have some as applicable as SLA or L2, the problem with it is exactly that applicability, how the researcher is a pawn in this system of power, in this case the education system, complicit, if not complacent, functioning to provide legitimation for the system of power. The researchers should be aware of that, always keeping that in mind, and “struggle against the forms of power that transform him into its object and instrument in the sphere of ‘knowledge,’ ‘truth,’ ‘consciousness,’ and ‘discourse’”, as aptly put by Foucault (208).

Unformed matter, formed matter and form

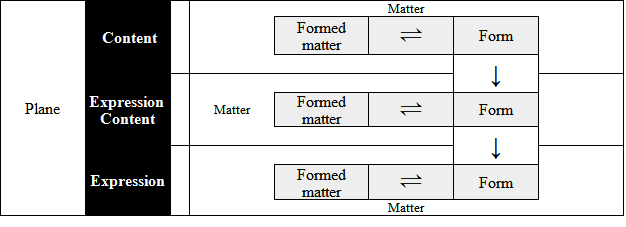

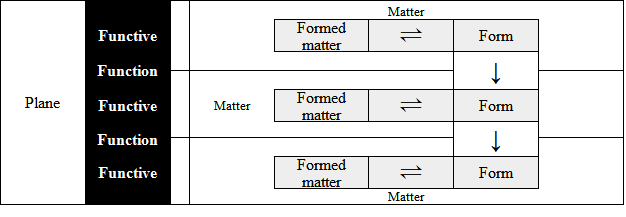

Having explained content and expression, Hjelmslev (31) moves on to explain his definitions of substance, form and purport. However, before I elaborate on his definitions, it is worth noting that mening (Danish for meaning) is translated as purport by the English translator, Whitfield, whereas the French translators, Una Canger and Annick Wewer, opt for sens (sense). While all of these, mening, purport and sens, work, conveying the same meaning, purport, or sense, none of them is very intuitive. Hjelmslev (31) refers to it as “an amorphous mass”, as “an unanalyzed entity”, which is defined only in relation to sign function or, in short, function. When we think of it in terms of function, yes, meaning, purport or sense, are all apt terms, as it has to do with that which is conveyed by whatever it is that is expressed. However, they are not that great when contrasted with substance and form. He (32) explains substance as that what is formed from purport by the form or, conversely, form as that which forms substance out of purport. In other words, purport is, in fact, the matter out of which substance is formed by the form. Therefore, we could also call purport matter and substance formed matter, as done by Guattari in his commentaries on Hjelmslev work.

For example, in ‘Hjelmslev and Immance’, Guattari (208) refers to purport as matter-meaning continuum, divided into content and expression continuums by Hjelmslev. In ‘The Role of the Signifier in the Institution’, he (73) refers to matter, substance, and form, although he (73) also opts to call matter meaning. He (95-96) does the same thing in ‘Towards a Micro-Politics of Desire’, noting that what Whitfield has opted to translate as purport is, on one hand, about matter, but, on the other hand, about meaning or sense. In ‘A Thousand Plateaus’ Deleuze and Guattari (3, 40-41, 43-45, 49, 53, 56, 61, 72, 141, 146, 165, 225, 258, 267, 338, 340, 503, 505, 511, 531) refer to formed matter, i.e., substance or materials, and unformed matter, i.e., matter or meaning (purport or sense).

In summary, we have matter-meaning, either as the unformed matter or as the meaning, purport or sense when it is considered in relation to a sign function or, in short, a function. In other words, we have meaning, purport or sense, which we know to exist, to be there, or so to speak, but we cannot explain it in its own terms. We get to meaning, purport or sense, yes, we reach it, but it appears only in the function, once we link content and expression. This leads us to form.

Hjelmslev (32) notes that matter is unformed, existing solely for the purpose of acting as a substance for a form, whatever that may be, which means that substance is formed matter. Therefore, to be precise, substance is not substance for form. Instead, matter is the substance for a form, which means that, in a sense, it would be more appropriate to refer to matter, or, rather unformed matter as substance, as opposed to using it the way he does. Then again, I think it would be preferable to refer to matter, which is to be understood as unformed matter when contrasted with formed matter that is relevant only when we also take form into consideration.

The problem here is that not only has Hjelmslev added one more concept to Ferdinand de Saussure’s system, purport (matter-meaning), and renamed signifier and signified as expression and content. Instead, he has reworked the whole system, as explained by Oswald Ducrot and Tzvetan Todorov (21-22) in ‘Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Sciences of Language’. In summary, Saussure’s substance, “semantic or phonic reality considered independently of any linguistic utilization”, is Hjelmslev’s purport (matter-meaning) and Saussure’s form, “segmentation” or “configuration” is Hjelmslev’s substance (formed matter), so that the added concept is not purport (matter-meaning), but form, to be understood as “the relational network” which defines substance (formed matter).

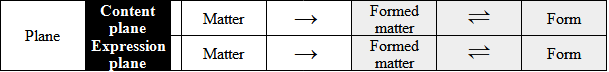

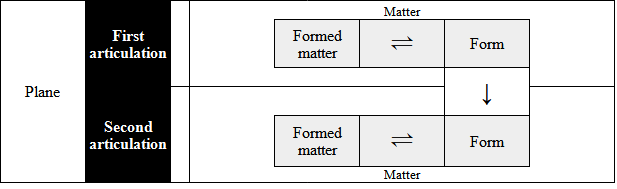

Isomorphism

To link Hjelmslev’s substance (formed matter) and form to content and expression, it would appear that there is no reason to consider content any different from expression, considering that both have substance (formed matter) and form, as noted by Ducrot and Todorov (22). Their form is identical, is it not? Ducrot and Todorov (22) acknowledge that this is indeed the case, that their forms are identical, that there is isomorphism, i.e., that they share the same logic of “combinatorial relations among units”, but that does not mean that there is correspondence or conformity between the two, that they are realized the same way. There is unity but also variety, as explained by Deleuze and Guattari (46) in ‘A Thousand Plateaus’:

“The same formal relations or connections are then effectuated in entirely different forms and arrangements.”

They (85-86) further elaborate this:

“[W]e are presented, despite the variety in each of the sets, with two formalizations, one of content, the other of expression. … Precisely because content, like expression, has a form of its own, one can never assign the form of expression the function of simply representing, describing, or averring a corresponding content; there is neither correspondence nor conformity. The two formalizations are not of the same nature; they are independent, heterogeneous.”

In other words, what’s in common between the two, content and expression, is that they both appear as forms, hence the isomorphism, and that’s that, which is why they are still distinct from one another, why they do not collapse into one another.

Guattari (337) further comments on this in ‘The Machinic Unconscious: Essays in Schizoanalysis’, noting that this isomorphy is, in his view, never perfect. Why? Well, because the two forms, form of content and form of expression, never represent, describe or aver to one another. Taking his comment into account, it seems that referring to it as isomorphy is slightly off. The basic principle is there, they are both forms, yes, both sets of relations, one for content, one for expression, yes, that makes them isomorphic, but that’s about it.

I guess this is why Deleuze (61) states in his book on Foucault, titled ‘Foucault’ that “there is no isomorphism or conformity” between the two, only mutual presupposition and, more elaborately, that (31):

“But the fact remains that the two formations are heterogeneous, even though they may overlap: there is no correspondence or isomorphism, no direct causality or symbolization.”

This is still, well within what’s been covered so far. He (61) exemplifies this:

“[T]here is neither causality from the one to the other nor symbolization between the two, and that if the statement has an object, it is a discursive object which is unique to the statement and is not isomorphic with the visible object.”

So, as already pointed out, the only isomorphy you’ll find pertains to the forms, that the form of content and form of expression are both forms. To be honest, I don’t know what caused this change of heart. This has puzzled me for a long time. I mean Deleuze and Guattari, together and on their own, seem to be talking about the same thing, but in one instance it is deemed to be about isomorphy but in another instance it isn’t. Maybe this is one of those things where people ended up thinking that isomorphy meant correspondence between the forms, which it isn’t, so Deleuze ended up dropping it in his book on Foucault. Maybe it’s about Foucault’s views, instead of Deleuze’s views. Then again, I doubt that. He is clearly explaining Foucault’s views through his own views, at times comparing them, so it’d be odd that he’d be merely explaining Foucault’s views while defining the relation between the forms the same way as he does with Guattari in his own works. I think Guattari’s (337) comment about the lack of “a perfect isomorphism” or the incongruity of the forms is helpful here. It’s like there is a certain isomophism, a certain degree of isomorphism, yes, in a sense, but, strictly speaking, there isn’t isomorphism.

This leads Deleuze and Guattari (86) to comment that Stoics were the first to grasp how bodies (the corporeal content), in the broadest sense of the word, like a lake as a body of water, and statements (the incorporeal expressions) were independent from one another, so that one incapable of altering the other, which is also what Spinoza argues (131-132) in his ‘Ethics’, how thoughts can only affect other thoughts and how bodies can only affect other bodies.

This is not to say that the statements (expression) do not intervene with bodies (content), as they do, as they are only attributable to bodies, but the bodies themselves are not altered, as Deleuze and Guattari (86) go on to add. This is also not to say that bodies (content) do not matter, as they do, as they (86-87) point out. But instead of thinking of one or the other, content or expression, in isolation, we should think of them in combination, “[s]o that the same x, the same particle, may function either as a body that acts and undergoes actions”, as an A, “or as a sign constituting an act”, a speech act, to be more specific, as a B, “depending on which form it is taken up by”, the form of content or the form of expression, as they (87) point out.

Spinoza would agree with this , considering that, in his ‘Ethics’ (45, 55, 132), the human mind and the human body are one and the same thing, a mode, a modification of substance, conceived under one of the two attributes that constitute the essence of substance that we humans are aware of, thought or extension. In his (131-132) words:

“Thus it follows that the order or concatenation of things is identical, whether [substance] be conceived under the one attribute or the other; consequently the order of states of activity and passivity in our body is simultaneous in [substance] with the order of state of activity and passivity in the mind.”

Which, for him (86) amounts to saying that:

“The order and connection of ideas is the same as the order and connection of things.”

It is worth noting here, before I continue to comment on content and expression, that Spinoza’s view of attributes sharing the same order and connections between the modes is often referred to as parallelism, but he never actually uses that term in his works. Instead, as noted by Deleuze (107, 365) in ‘Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza’, parallelism is attributable to Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (556) who uses it to in ‘Reflections on the Doctrine of a Single Universal Spirit’, to distinguish his own monist views from (Cartesian) dualist views:

“Those who favor a universal spirit will readily assent to this, for they distinguish this spirit from matter. I find, however, that there is never any abstract thought which is not accompanied by some images or material traces, and I have established a perfect parallelism between what happens in the [mind] and what takes place in matter.”

Note how he states that his views are not only marked by a parallelism but a perfect parallelism. Anyway, he (556) continues:

“I have shown that the [mind] with its functions is something distinct from matter but that it nevertheless is always accompanied by material organs and also that the [mind’s] functions are always accompanied by organic functions which must correspond to them and that this relation is reciprocal and always will be.”

Conversely, while advocating for “the doctrine of parallelism”, he (556) argues against a perfect separation of body and mind. In addition, while explaining this, he (556) argues, or at least seems to argue, that mind always retains something of the body, which, I’d say, is something that Spinoza would not be willing to state. It is also worth mentioning that while Spinoza is acknowledged in this text, being given thumbs up for his monism, “his demonstrations are” considered to be “pitiful and unintelligible” by Leibniz (555). Therefore, I’d say that parallelism is attributable to Leibniz rather than to Spinoza, as pointed out by Deleuze (106, 365).

Deleuze (107) further elaborates this:

“When Spinoza asserts that modes of different attributes have not only the same order, but also the [s]ame connection or concatenation, he means that the principles on which they depend are themselves equal.”

Exactly! If you look at how Spinoza (86) explains that, the order and connection of ideas (thoughts, thinking things) are the same as the order and connection of things (bodies, extended things), not that the ideas and the things are the same, that they parallel one another. In other words, there is only isomorphism, a shared logic of “combinatorial relations among units” but no correspondence, nor conformity between the two, which matches Hjelmslev’s take on content and expression, as explained by Ducrot and Todorov (22).

You could, of course, still call isomorphism a kind of parallelism, in the sense that there is indeed a shared logic, “the equality of the principles from which independent and corresponding series follow”, as noted by Deleuze (108-109). I agree with this. That seems to be the case.

You could also insist that, for Spinoza, a mode considered under one attribute is paralleled with a mode considered under the other attribute, as noted by Deleuze (108-10). I am, however, a bit doubtful of whether this holds or not for Spinoza, whether he thinks that the idea of a thing (a thought of it) is matched by the thing (the body in question). For example, he (83) reckons that we humans think and that we can think of not only something that exists but also something that does not exist, in the sense that we can think of a person who no longer exist, who no longer lives. This is what he means when he (82) says that an idea is a matter of conception rather than perception, something involves thinking rather than passively receiving information of what’s out there, beyond us. He (82) also states that an idea is only adequate, i.e., not confused, when it is considered intrinsically, in itself, on its own terms, as opposed being considered extrinsically, in relation to an object.

He (113) clarifies this by differentiating between three types of knowledge. The first kind of knowledge he labels as opinion or imagination, what we get from perception or having read or heard something which offers us fragments or confused knowledge. The second kind of knowledge he labels as reason, what we get from common notions, i.e., what is shared between this and/or that, whatever it may be. The third kind of knowledge he labels as intuition, which is what we get when we understand not the things but their essences, what it is that makes this this and not that and vice versa, for example what makes me me and not you and you you and not me or what makes hurricane Gordon hurricane Gordon and not hurricane Mitch and vice versa. Deleuze and Guattari (263-264) make note of this in ‘A Thousand Plateaus’:

“[T]he proper name is no way the indicator of a subject[.] … [It] does not indicate a subject; nor does a noun take on the value of a proper name as a function of a form or species. [It] fundamentally designates something that is of the order of the event, of becoming or of the haecceity.”

This is followed by a couple of examples which help us to understand why proper names are not just about me or you, as markers of subjects or as functions of objects, i.e., how we are, for example, humans, mammals, and animals, but about something else, as they (264) point out here:

“It is the military men and meteorologists who hold the secret of proper names, when they give them to a strategic operation or a hurricane.”

That’s why, for them (264), “the proper name is not the subject of a tense”, something that we could replace with a noun or a pronoun, “but the agent of an infinitive.” This hints to Spinoza’s definition of all things having a modal essence, i.e., degrees of expressive power or intensity pertaining to their capacity to act and be acted upon, and modal existence or non-existence, how things are always composite things, how they always consist of other things, to use the terms introduced by Deleuze in chapters 12 and 13 of ‘Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza’. A thing, everything and everybody, be it a thinking thing (an idea or a thought) or an extended thing (a body), always has latitude, i.e., “intensive parts falling under a capacity”, and longitude, i.e., “extensive parts falling under a relation”, as summarized by Deleuze and Guattari (256-257) in ‘A Thousand Plateaus’. In short, a thing, me and you included, is no longer to be understood nor recognized for what it is but for what it can do and what others (that can also do) do to it, as explained by Deleuze and Guattari (256-257).

Anyway, to go back a bit, just a bit, it is worth adding here that, for Spinoza (109-114), we get from the first to the second kind of knowledge and from the second to the third kind of knowledge, and that the first kind of knowledge is inadequate knowledge, whereas the second and the third kinds of knowledge are adequate knowledge. The first kind of knowledge stems from the limitations of being a human, a mere human, a limited body that is capable of distinguishing only so many things at the same time, continuously exceeding this limit, which results in confusion.

The second kind of knowledge is adequate because it is about reason, about rationality, about ratiocination, about the ratios of parts and wholes and how they agree with one another, as clarified by him (109-111). I’d say that Hjelmslev is dealing with this kind of knowledge as he is concerned with the relations between parts and wholes.

Spinoza doesn’t spell it out for you, but the third kind of knowledge, intuition, is adequate because it pertains to essences, what makes substance what it is, substance. What makes the third kind of knowledge superior to the second kind of knowledge is that while both are adequate kinds of knowledge, the second kind of knowledge is limited to dealing with what is common between this and/or that and therefore does not pertain to essences, as essences are always particular or singular, whereas the third kind of knowledge does pertain to the essences of things, what is particular or singular about something or somebody.

Deleuze (104-105) further comments on this, noting that, for Spinoza, each statement (expression) carries a distinct sense while also designating an object (content), which then becomes a designated object (content) for another statement (expression) that comes to function as a distinct sense, which, in turn comes to function the same way, ad infititum. To my understanding, this is what Deleuze (19-21, 39-40) also states in ‘The Logic of Sense’, how sense appears in the expression as that which is expressed, subsisting or inhering to it, but without being it, as the event that takes place between what Deleuze and Guattari refer to as the expression (words) and the content of the expression (things), and how, once expressed, it can always double as the content for another expression. Importantly, this doubling is very flexible, allowing us to address the relations between the semiotic and the non-semiotic, as in between words and material things, as well the relations within the semiotic, as he Deleuze (37) points out. This can also be extended to cover the relations between the non-semiotic, as done by Deleuze and Guattari in ‘A Thousand Plateaus’, albeit that is, of course, done through the semiotic as we cannot explain it, put it in words, without doing that through the semiotic.

In summary, Hjelmslev’s content and expression are, in a sense, the same, yet they are, in a sense, different. This is the same for Deleuze and Guattari who takes these from Hjelmslev. To clarify this, how they can be the same, yet different, we must pay close attention to Spinoza’s train of thought. As already pointed out, all modes are modifications of substance, conceived under one of the two attributes, thought or extension, which, in turn, constitute the essence of substance, among other attributes of which there are infinite (we just know the two). In other words, there is always this link between the modes and the substance as modes can only be conceived through attributes that constitute the essence of substance. To be clear, this does not mean that expression functions by having a content that it points to, like words pointing to corresponding things or things that conform to them.

Plane-matter

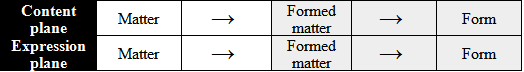

To make more sense of this, all of this, what has been covered so far, I’m going to explain how Hjelmslev’s net functions, step by step. Let’s start with matter, also known as meaning, purport or sense (II).

I could have labelled matter as meaning, purport, sense or matter-meaning, but, for the sake of clarity, I think it is apt to just call it matter here. I have included plane here, to indicate that there is only one plane, what Deleuze and Guattari (72) briefly refer to as “the Matter of the Plane” in ‘A Thousand Plateaus’.

The plane of consistency

Deleuze and Guattari tend to refer to this plane also as a plane of consistency. It is mentioned so many times in ‘A Thousand Plateaus’ that it is pointless to provide you the page numbers for all of those instances. Relevant to Hjelmslev, it is discussed in the chapter, or, rather plateau known as ‘The Geology of Morals’. They (43) point out that:

“[Hjelmslev] used the term matter [matière] for the plane of consistency or Body without Organs, in other words, the unformed, unorganized, nonstratified, or destratified body and all its flows, subatomic and submolecular particles, pure intensities, prevital and prephysical free singularities.”

In other words, Hjelmslev’s matter is Deleuze and Guattari’s plane of consistency. But what is plane of consistency or, rather, what is consistency? Well, the thing is that they keep mentioning it, but it takes some 300 pages or so for them (323) to provide a definition beyond their (144) earlier remark about it being “neither totalizing nor structuring”:

“[C]onsistency: the ‘holding together’ of heterogeneous elements.”

To be honest, that is how I would think of consistency, how something, whatever that may be, holds together. Massumi (xiv), their translator, notes in his foreword to the book that it is exactly that, but further specifies it, warning not to think of it as about homogeneity but about “holding together disparate elements”, what Deleuze calls style in ‘Proust and Signs: The Complete Text’, “a dynamic holding together or mode of composition”, so that when we say that something has style, that style is not a given, but that what appears to us as that style, composed of a bit of this and a bit of that, whatever it is that gives it that style.

To me, style is like that, how it comes together. I don’t know how I ended up watching a short video, but the gist of that video was covering a photoshoot done at a movie set. You could say it was just a basic model shoot, a model posing for a camera in some location, which happened to be a movie set, but that’s not all there was to it. The photos were shown on the video, matching the moments when they were taken, to see what the photographer was able to render visible to us. Then again, it is not just about the photographer. The style of those photos are much more than just the photographer and much more than a camera, a model and a background. The thing is that they had this 1970s vibe to the set, as did the model’s attire, hair and makeup, and the photographer shot it with a medium format SLR, on film, which results in this … style, this consistency of all of those elements, including the lighting, that come together in those photos.

The Spinozist take: the plane of immanence

Elsewhere in ‘A Thousand Plateaus’, Deleuze and Guattari (254-255, 266, 268-269, 281-282) also refer to the plane as a plane of immanence. The first time this appears in the book, they (253-254) are discussing Spinoza. That’s why they call it that, the plane of immanence.

They (254) note how Spinoza’s substance (Hjelmslev’s matter, not Hjelmlev’s substance) is like a plane “upon which everything is laid out.” To use Spinoza’s (45, 59, 82) own definition, it is that which is self-caused and from which everything else necessarily follows, so that there are “an infinite number of things in infinite ways”. In addition, substance is, by his (46) definition, that which exists by itself, which makes it eternal, so that everything else owes its existence to it. In short, (Spinoza’s) substance is, in itself and for itself, expressive, as explained by Deleuze (99) in ‘Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza’.

What else is there then for Spinoza? Well, as already explained, for Spinoza (45), there are also attributes and modifications of substance or, in short, modes. For him (45), attributes are what constitute the essence of substance. For substance to be both essential and infinite, i.e., infinitely essential, its constitution must involve infinite attributes, as he (45) points out. As already noted, we, as humans, are aware of two attributes, extension and thought. In terms of modes, what he (82) also refers to collectively as things, we have bodies (extended things) and thoughts (thinking things), which express the essence of substance. Highly importantly, the existence of modes depends on their essence, as indicated by him (46, 82). Simply put, you do not exist, nor does anyone, nor anything else, if they are not essentially extended. It is essential that they are. It is the same with thoughts. They are understood as such only by virtue of that essentiality. It’s a simple yes or no thing. It’s as simple as that. That said, an essence will do just fine without a mode, i.e., an existing body or thought, as he (83) goes on to add. For example, the existence of this table that I write on is not necessary to its essence as it is possible to conceive its essence even in its absence, nor is my idea of a table necessary for others to conceive it as a table. This leads us to the distinction between attributes and modes, how attributes pertain to modal essence, to “a particular or singular essence”, for example what makes this table this table and not some other table (otherwise this table would be some other table), whereas modes pertain to modal existence, whether this or that mode, i.e., thing, exists or not, as summarized by Deleuze (192-193, 201) in ‘Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza’.

As an additional note on translation, which may be of interest to those interest in affect, it’s worth commenting that in the Latin original the modifications of substance are “substantiæ affectiones”, which could then also be translated as affections of substance. The problem with translating that as affections is that, according to a dictionary, such as the Oxford English Dictionary, these days one typically understands it (OED, s.v. “affection”, n.1) as about feelings:

“The action or result of affecting the mind in some way; a mental state brought about by any influence; an emotion, feeling.”

I might be wrong about this, but I reckon Spinoza isn’t going for this definition. Instead, he builds on an older, more general sense of the word (OED, s.v. “affection”, n.1), which is rarely used in such a way these days:

“The action of affecting, acting upon, or influencing something; (also) the fact of being affected.”

The origin of the English word is in Latin, which a dictionary (OED, s.v. “affection”, n.1) will tell you as being about “mental or bodily condition”. I think this is worth emphasizing, how, for Spinoza, affect is therefore not only about the body or about the mind, but about the body and the mind. This makes sense, considering that Spinoza’s affections of substance pertain to how both bodies and thoughts are indeed modifications of substance, having this or that bodily or mental condition, existing in this or that state, as the substance undergoes affections or modifications.

I believe Spinoza’s choice to call them affections of substance is particularly apt if we take a closer look at the core of his ethics in which everything, whatever we are referring to, let’s say you or me, to keep things interesting for us, you and me, is defined as having the capacity to act and be acted upon, as he (215) explains this:

“Whatsoever disposes the human body, so as to render it capable of being affected in an increased number of ways, or of affecting external bodies in an increased number of ways, is useful[.]”

What’s worth noting here is that affect or, rather, affecting, is always tied to the affections (or modes), to those affections (or modifications) of substance that are defined according to their capacity to act and be acted upon, which is another way of saying capacity to affect and be affected. This applies to everything, to every affection or mode, which makes this relational.

Deleuze explains this particularly well during his lectures on Spinoza in January 24, 1978:

“The only question is the power of being affected.”

Now, there is an emphasis on the bodies, yes, as opposed to thoughts, yes, which would make affect only about bodies, but if you read Spinoza’s ‘Ethics’, his own handy definition of affections or modes also takes thoughts into account. He (174) states that we experience pleasure and pain, the former involving “the transition … from a less to a greater perfection” and the latter involging “the transtition … from a greater to a less perfection”. So, for example, if I were to blind you, you’d then be less perfect in the sense that you’d be less able to act (e.g. can’t see where you are going) and be acted upon (e.g. can’t see what others are showing you). But if I were to provide an eye surgery, assuming you have poor sight, it would then result in a greater state of perfection, because you capacity to act and be acted upon would be increased. This is clearly very bodily. There’s no doubt about that. There’d be pleasure in better eyesight and pain in having no sight. Now, we can do the same with thoughts. If I were to threaten you, or come across as threatening, having, for example, blinded people in the past or there being stories of such, just the thought of it, pondering what are the odds that I might blind you, is enough to limit your capacity to act and be acted upon, because now you do your best to avoid me, regardless of whether I have or have not blinded anyone in the past. Note how I’m not doing anything to you physically, body on body, yet, it appears that I have had a certain effect on you. Such fear may also have the effect that, perhaps, you end up having physical symptoms, vomiting or the like, just by thinking that, that I might be a physical threat to you, even in the case that I am not (and I am not, to be clear), when it’s just hearsay.

In his letter to Lodewijk (referred to also as Louis and Lewis) Meyer, Spinoza (282-283) explains to Meyer that it is crucial not to confuse the infinity and eternity of (Spinoza’s) substance with the spatial and temporal finitude of the modes. In other words, (Spinoza’s) substance is indivisible, whereas modes are divisible (albeit infinitely). Deleuze (201) explains this in ‘Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza’:

“I do not think that there are, for Spinoza, any existing modes that are not actually composed of a very great number of extensive parts.”

To make more sense of this, what he (287) means by “a very great number” has to do with something that cannot be determined by, nor assimilated with any number, as explained by Spinoza (282, 287).

This means that we cannot argue that (Spinoza’s) substance consists of modes, because what is indivisible cannot, as a whole, consist of divisible parts, as he (283) points out. He (283) exemplifies with how we are tempted to think that a line is consists of points, even though it isn’t (or it is, but then conceived as consisting of infinite points). Also, keep in mind that substance is not made up of modes as modes are modifications of substance, as already pointed out. In other words, modes depend on substance, not the other way around.

You might be wondering why even mention that substance is indivisible, whereas modes are divisible. Well, this is because Spinoza (283-284) goes on to make a crucial point quantities or quantification, something that people often fail to grasp. In his (283-284):

“[W]e conceive quantity in two ways, abstractly … and superficially; … superficially in so far as we imagine quantity through the senses; abstractly when the conception is in the understanding only.”

In other words, there are two ways to think of this, abstractly, what he considers to be correct, and superficially, what he considers to be incorrect. He (284) further elaborates this:

“Now, if we consider quantity as it is in the sense and the imagination – and this indeed very readily and most commonly happens – we then find it divisible, made up of parts and multiple; but when we consider it abstractly, as it is in the intellect and a thing per se, which it is extremely difficult to do, then do we perceive it to be … Infinite, Indivisible and One.”

The point he makes here is that when we think of quantity, we are tempted to think of it as about numbers, but that’s, strictly speaking, incorrect. He (284) acknowledges the utility of the superficial conception of quantity, helping us to make sense of time and space, but that’s that for him, just about utility. In other words, quantities should not be confused with numbers, even though that’s exactly what people do, even most academics (hence poorly or inadequately conceived distinction between qualitative and quantitative studies, but that’s another story), as numbers offer just a way of conceiving quantities. To be clear, numbers and quantities are not the same thing, nor do numbers determine quantities, as he (285) points out. We can, of course, determine quantities numerically, but numbers do not determine quantities as quantities are not, in themselves, numbers. To use his (285) terminology, number is an image of quantity, a way to imagine quantity, but not quantity itself, which is why he summarizes this as:

“From this it is clear that measure, time, and number, are nothing but modes of thinking, or rather of imagining.”

If you fail to grasp the distinction, what he explains here, keep in mind that a meter (or a foot), a square meter (foot) or a cubic meter (foot) are measures of space, not space itself, just as a second, a minute and an hour are measures of time, not time itself (what Spinoza refers to as duration, as does Henri Bergson, time being treated as the measure). So, when we ask how much time we have left or how much space is there, we are treating time (duration) and space as something that they are not, reducing them into something that is measured out of convenience and, I’d say, habit.

But what’s the problem with equating quantities with numbers? Isn’t this just an exercise in pedantry? Does it even matter in practice? What difference does it make? Well, while we may go about our lives, happily ignoring this, the problem with equating quantities with numbers is that creates a whole host of problems that we have to deal with, as he (284) goes on to point out.

He (285) exemplifies these problems and the absurdities it results by noting that the way we are tempted to think time works, divisible into certain measures of time, pushes us to make sense of each of these units by dividing it again and again, ad infinitum. He (285) asks us to consider what is an hour anyway? If you divide it, you get half an hour, then a quarter of an hour and then something that becomes harder to think, seven and half minutes, followed by 3 minutes and 45 seconds and so on and so forth, the point being that this way an hour never passes by, as he (285) points out, hence the absurdity of it. We could, of course, divide an hour by minutes and then by seconds, followed by fractions of seconds, but we’d run into the same nonsense.

For those who are interested in this issue, Aristotle mentions similar absurdities, commonly known as Zeno’s Paradoxes, in his ‘Physics’ (book VI, part 9), such as how the slowest runner can never be overtaken by the fastest runner because, while gaining on the slowest runner, halving the distance amounts to just that, halving the distance, and how an arrow can only be motionless as it can only occupy a certain place in space at any given moment. Aristotle rightly points out that you are an idiot if you think like this because time is not composed of moments.

Something tells me that you are now thinking that no one is that stupid, like come on, and I agree with you that no one thinks that a slower runner cannot be overtaken by a faster runner, nor that an arrow is motionless. That’s not, however, the problem here. The problem here is that people do regularly conflate time (duration) with the measure of time and space with the measure of space (not to mention that the measure of time is, in fact, a measure of space, based on the movements of astronomical objects), as they do with numbers and things (bodies and thoughts), as explained by Spinoza (285). In summary, the problem is that people “do in fact deny the Infinite”, as he (285) points out.

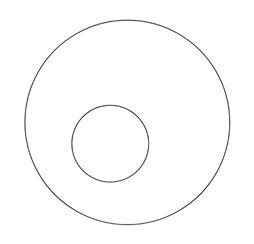

He (286) exemplifies the inadequacy of numbers, how numbers are not the same thing as quantities by presenting two non-concentric circles (III):

His (286) rendition looks slightly different, the size of the smaller circle being a bit larger and having named the larger circle A B and the smaller circle C D, but the differences in rendition don’t change anything. The point he (286) makes is that there are infinite positions for that smaller circle within the larger circle or, conversely, that there are infinite positions for that larger circle around the smaller circle. Numerical computation is of no use here, as he (286) points out.

The funny thing is that while we can conceive infinity as something that is unlimited or unbounded, we can also conceive infinity as limited or bounded, what he (287) also refers to as indefinite. To clarify this, in his ‘Ethics’ he (45) refers to the former as absolute infinity and to the latter as infinity after its kind. He explains this well in his letter to Meyer, but I believe the point he wants to make in his ‘Ethics’ with this distinction is to make sure that you do not lapse into thinking that there is something that is separate from substance from which everything else necessarily follows.

He (227) explains this better in one of his letters to Henry Oldenburg, noting that if we think of space as space, on its own terms, as pertaining to the attribute of extension, as one of the essences of (Spinoza’s) substance, it must be unlimited, i.e., absolute. If, however, we define it as limited by thought, then it is limited or bounded, it can only be infinite after its kind, in terms of space. We can also explain this by flipping this on its head. What I mean is that if the example he uses in his letter to Meyer wasn’t about infinity after its kind, that is to say infinite only in terms of space (extension), then he’d be contradicting himself, considering that, for him, only substance is absolutely infinite.

Anyway, as you can see, there is a maximum, as defined by the limits of the larger circle, and a minimum, as defined by the limits of the smaller circle, as indicated by Spinoza (286) in his letter to Meyer, so that we could even argue that it is possible to conceive a larger or smaller infinity if we alter the size of the circles, while maintaining that, be that as it may, we are still faced with infinite positions for those circles, as he (287) goes on to specify. Deleuze (204) comments on this, noting that it is indeed possible then to state that a mode has an infinity of parts, as does any mode, while also stating the infinity of its parts is, for example, double that of another mode without there being any absurdity to that.

Spinoza (286) acknowledges that you can, of course, use numbers, indicate the numerical size of one of the circles from which you can then calculate the size of the other circle or the numerical sizes of both circles, but that is beside the point, as that’s not what he is after here. In his (286) words:

“[The person] who would attempt to express all the inequalities of such a space by numbers must begin making the circle something else than it is.”

Again, this is not to say that we no longer have any use for numbers, nor that we can’t think of things as finite and divisible, as acknowledged by him (287), but rather that when we take a moment to think about this, it’s clear that’s not how things really are. We cannot rely on numbers to explain Spinoza’s substance or Hjelmslev’s matter. It would indeed be like “making the circle into something else than it is”, as Spinoza (286) points out.

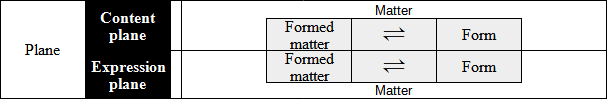

I think Spinoza’s definitions of substance and its modes are quite useful as they help us to understand how, for Hjelmslev (32, 34), matter is a continuum, an amorphous mass or zone. What I mean is that when we have, for example, a continuum of sounds, there are infinite alternatives for laying down boundaries in this amorphous mass or zone, for gridding it, which results in a different number of figuræ (for sounds: phonemes), as pointed out by Hjelmslev (34-35). In his words (35):

“[T]he possibility that language can make use of are quite indefinitely great; but the characteristic thing is that each language lays down its boundaries within this infinity of possibilities.”

Make note of how he (35) uses the words ‘indefinitely’ and ‘infinity’ to explain this, matching Spinoza’s (287) definitions of unbounded infinity, pertaining to (Spinoza’s) substance, in itself, in its own terms, and bounded infinity or the indefinite, pertaining to the modes, to the modifications of (Spinoza’s) substance. In other words, explain this how Spinoza (45) explains this in his ‘Ethics’, (Hjelmslev’s) matter is, in itself, absolutely infinite, whereas, once specified, as this or that kind of matter, as formed matter, matter is merely infinite after its kind.

To be clear, the continuum of sounds discussed by Hjelmslev (34) is, of course, a bounded infinity, that is to say indefinite, as the production of sounds is bounded by the relevant parts of the human body, as also evident from his (35) examples. There are infinite ways to produce sounds within those bounds. In addition, those bounds also differ from person to person, so that one person’s infinity can therefore be larger or smaller than someone’s else. It is worth noting that the indefiniteness of this, the bounded infinity, has to with how the continuum is limited, pertaining only to sounds or, rather, the production of sounds. In other words, this continuum is not the continuum, matter itself, but rather a modification of it, which is why it is a particular continuum. If it were the continuum, about continuity itself, it would have no boundaries and we’d be dealing with matter.

It is the same with a thought continuum, what Hjelmslev (32) also refers to as an amorphous thought mass, as each language segments it in different ways. In his (32) words:

“Each language lays down its own boundaries within the amorphous ‘though-mass’ and stresses different factors in it in different arrangements, puts the center of gravity in different places and gives them different emphases.”

This simply means that there are infinite ways to segment a continuum into a number of minimal units, what Hjelmslev (34) calls figuræ (figures). In this case a continuum of sounds is segmented into a number of minimal (meaningless) sound units known as phonemes and a continuum of thoughts is segmented into a number of (meaningful) minimal thought units known as morphemes (or monemes). Guattari (207) comments on this:

“What defines a language is not signification, but its capacity for reproducing an infinity (a flow) of signs, given a finite (axiomatic) figure machine.”

Hjelmslev (32) elaborates on this:

“It is like one and the same handful of sand that is formed in quite different patterns, or like the cloud in the [sky] that changes shape. … Just as the same sand can be put into different molds, and the same cloud can take on ever new shapes, so also the same [matter] is formed or structured differently in different languages.”

Which means that, as noted by Guattari (207), for Hjelmslev (32):

“What determines its form is solely the functions of the language, the sign function and the functions deducible therefrom.”

To be clear, to make sure that you don’t think that matter disappears once it is formed into formed matter in relation to form, Hjelmslev (32) adds that:

“[Matter] remains, each time, [matter] for a new form, and has no possible existence except through being [matter] for one form or another.”

In other words, while matter is formed into formed matter, it is not irreversibly reduced into formed matter.

Right, it is time to return to the discussion of plane of immance. Deleuze and Guattari (254) warn their readers not to confuse these elements with atoms, as atoms are “finite elements … endowed with form”, whereas these elements do not have form, as already established. They (254) warn their readers not to think that these elements can be “defined by their number” as “[t]hey are infinitely small, ultimate parts of an actual infinity”, i.e., infinitesimals and infinities, “laid out on the same plane of consistency or composition.”