The Baltic Carrier Accident in 2001 (3/4): Who’s in Charge?

Read parts 1 and 2, here.

Written by Kia Friis Petersen, Danish Civil Protection League

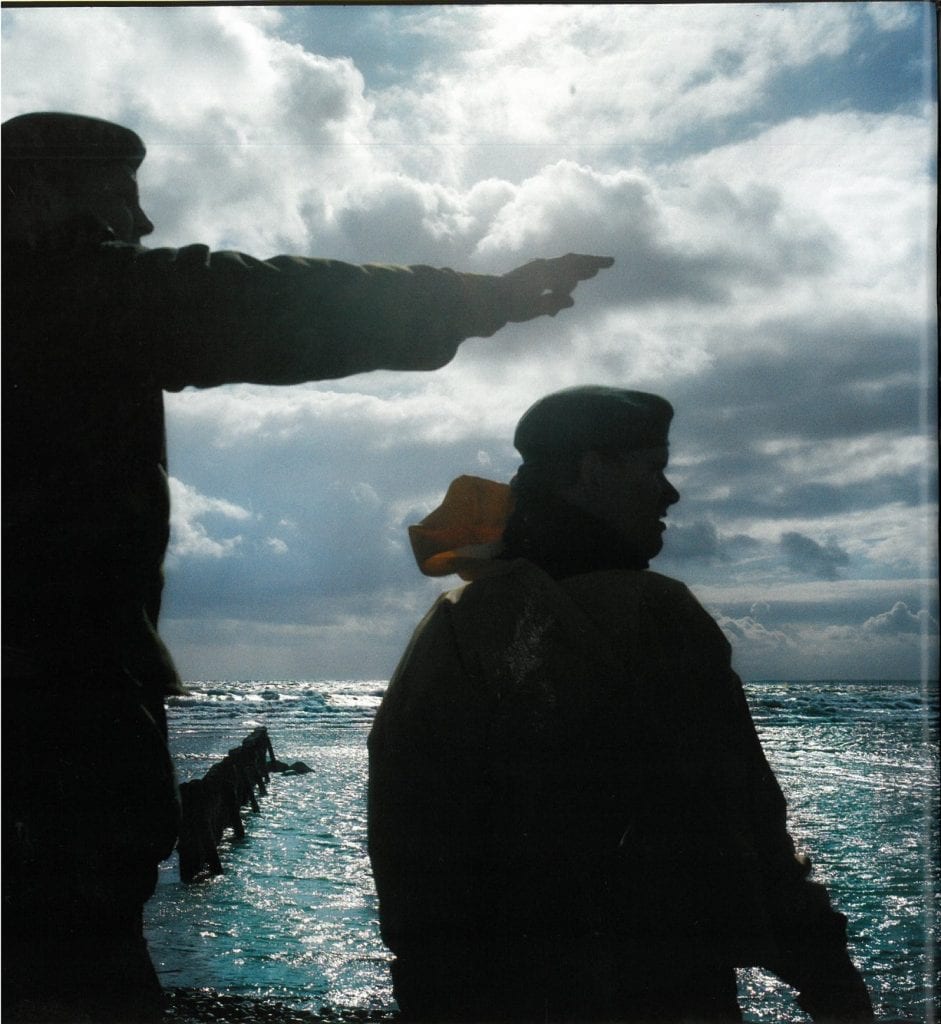

An oil spill drifting into a narrow belt will most likely not hit the shore in one place – but in several places. And that is exactly what happened when oil from the Baltic Carrier drifted into the Belt of Groensund in the evening on 29 March 2001. Because the clean-up operation spread along the many shores of different islands, incident management was crucial – and it had to be coordinated across several authorities.

Incident management who?

In the Danish Act for the Protection of the Marine Environment, the responsibility of protection and cleaning in the event of an oil spill is divided based on the normal water baseline. On the seaside, the Navy leads the operation, and on the landside, the municipality is in charge. However, the Ministry of Environment Protection must coordinate the municipalities’ plans. In addition, the Minister of Defence can choose to take over the coordination or authorise the Navy or other authorities the entire coordination if an oil spill is particularly severe or extensive. The latter is what happened with the Baltic Carrier oil spill.

Incident management can be divided into two levels: operational and tactical. The operational incident management (OIM) was led by the Admiral Danish Fleet (ADF) from the operation centre at the police station in Stubbekoebing. Among the staff, there were the Chief in Command and officers from the Danish Emergency Management Agency (DEMA), the Chief Fire Officers and the environment employees of the five affected Municipalities, the local police, a liaison officer from the On-scene Commander at Gunnar Thorson vessel, a representative from Storstroem County, and the Forest District with a game consultant.

OIM was established on 29 March, being operational from 10.00 o’clock. It was operational until 9 April at 19.00 o’clock when the operation on the sea and in shallow waters was ended. OIM oversaw the operation on the strategic and coordinating level. This included decision making regarding which areas to prioritize as well as pointing out the vulnerable areas. It was also from OIM that the part of the operation on sea, which was controlled from land, was coordinated with a liaison officer from the On-scene Commander.

The tactical incident management (TIM) was placed at the parking lot on the Faroe island. It was led by an incident commander from DEMA. TIM was established during 29 March with an ongoing supplement of staff and support functions from DEMA. From here, the operation on land was coordinated, and it was operational until 11 April.

“In TIM, our greatest job was to handle the logistics. The teams had to be divided and sent to the various cleaning sites. Besides the equipment for personal protection and cleaning, we had to ensure that there were toilets, handwash facilities, tents for shelter, and food and water at all these sites,” Peter Søe says. “And all of it had to be coordinated with OIM and the operation centre at DEMA SJ.”

The operation centre at DEMA SJ provided most of the equipment used on the shores and ordered by TIM.

Incident management how?

In Denmark, there had not been many large incidents during the 1990s that required coordination on different levels. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, much of the war preparedness was dissolved, and the incident command system was not used either. The management system had to be redeveloped during the Baltic Carrier incident, Peter Søe says.

“The system we had previously might have been bureaucratic, but it was a setup for solving large incidents – from the management perspective. And this system did not exist anymore. In my position at DEMA, I had received education in coordinating larger incidents − and some of my colleagues had too. However, many had not had this kind of training, and it was not offered anymore. So, the general knowledge to handle large incidents was gone.”

Every evening, the staff from both OIM & TIM had a meeting in which the operation’s status was mapped and the necessary steps for the next day were discussed. The discussions were based on the amount of oil collected, reconnaissance of the area, and the amount of equipment available. As the oil drifted, the scenes of the accident changed continuously. Therefore, it was these daily meetings where the operation sites were planned.

Besides the abovementioned meetings, the two staff were communicating and coordinating the response throughout the entire operation. The Terrestrial Trunked Radio (TETRA) network was not tested in Denmark before 2007. Instead, the participating authorities had their own radios, which were incompatible and could not communicate. DEMA had a short-range radio in use, but a lot of the communication was via mobile phones. “This was a disadvantage when a message had to be delivered to multiple actors, making the communication a bit cumbersome, but in general it was efficient for the task,” Peter Søe says.

A municipal effort

In the first two weeks, the Navy was in charge of the overall operation with the help from DEMA, as prescribed in the Danish Act for the Protection of the Marine Environment. Hence, the division between sea and land was not set as the normal water baseline. The operators at sea reached as far in as possible and those at the shore as far out as possible.

When the operation at the sea and in shallow waters was coming to an end, OIM and TIM were shot down. The municipalities took over the clean-up of the beaches and shores that were still affected. The transition from the state to a municipal level was smooth, because the municipalities had participated as much as they could in the first phases. In each municipality, the cleaning was continuously led by the technical administrations, and the County handled the coordination between the municipalities.

It was Moen municipality that had been most affected by the oil. Therefore, after the closing of OIM and TIM, DEMA provided Moen with two professional advisers as additional support until the end of April. The other municipalities could also draw from the expertise of these advisers, but their main focus was on Moen.

The clean-up continued until summer. By the end of June 2001, almost all sites had been cleaned. The municipal workers, private entrepreneurs, and volunteers supported each other in the heavy work. After the cleaning had ended, the civilians assisted by using the containers set up along most beaches.

In the evaluation report by DEMA, a sub-conclusion states that the terms “normal water baseline” and “coastal areas” should be re-evaluated and specified. It had become very clear that these descriptions did not serve the authorities with a useful distinction between the municipalities’ and the Navy’s area of responsibility. However, generally, the result of the full operation was satisfactory.

Sources:

- DEMA, Development unit (2001). Bekæmpelse af olieforureningen efter “Baltic Carrier” – En tværgående evaluering og erfaringsopsamling.

- Danish Act for the Protection of the Marine Environment

- Peter Søe, Chief Fire Officer at Lolland-Falster Fire and Rescue Service (2020), interview.

Leave a Reply