In Sweden and Finland, the vernacular was to be used in the Divine Service (Holy Communion) from 1537 onwards. Therefore, texts had to be translated into Finnish. There had been some liturgical texts in Finnish even before the Reformation, (such as the Ave Maria or the Lord’s Prayer), but the first preserved Finnish texts date from the Reformation period.

The largest of the surviving codices is named after Mathias West, the chaplain and school master of the city of Rauma, who copied the texts included from older sources. Apparently, the oldest of Finnish codices is a fragment of the Uppsala Book of Gospels, produced and intended for usage in Sweden. This might seem a little bit odd, but there is a very natural explanation for this, as there were a great number of Finnish speaking inhabitants in Sweden. In fact, the first parish to appoint a Finnish preacher was the Finnish-speaking congregation of Stockholm. Besides these two codices, there is a number of other surviving manuscripts.

The oldest printed books in Finnish are Mikael Agricola’s works. Agricola had some collaborators in his translation projects, so he did not work entirely alone. All the same, Agricola was a quite productive translator and writer. He first published his Abckiria, a short ABC book to help Finns learn to read, which also included a catechism, probably in 1543. The book was inspired by and contained translated parts from Luther’s, Melanchton’s and Andreas Osiandern’s Catechisms. The Ave Maria prayer was also part of the book, and shows thus that the change from Catholic to Protestant theology was not always very abrupt, and many Catholic customs survived for quite some time in Finland after the Reformation.

Agricola then published his Rucouskiria in 1544, a very large and comprehensive prayer book, and followed this four years later with his magnum opus, Se Wsi Testamentti, the Finnish translation of the New Testament. This

Mikael Agricola hands the New Testament translation to King Gustav Vasa. This meeting probably never really took place, but the picture illustrates well the new hierarchical order of the Church and the Crown after the Reformation. Robert Wilhelm Ekman, 1853. Wikimedia Commons.

was published in 1548 after many troubles in the financing of the expensive printing. Subsequently, Agricola published three liturgical books and translations of Psalms and of some prophetical books of the Old Testament.

Mikael Agricola and his contemporaries created the Finnish written language, which was a very demanding but important task for the future of Finland. As the language was used in the Mass and written down, it certainly affected the identity of the Finnish people. It gave to the language a position held until then by Latin and Swedish only. The language of the common people became important in its own right. Translating parts of the Bible and theological works into Finnish meant that wholly new ideas and concepts were introduced to the language. This in turn enabled the birth of theological, legal, philosophical and to some extent political debate in the language.

There were other benefits, too. As the written language was created, it also made possible the unification of the different Finnish dialects towards a standardised language. This might well have been a necessary prerequisite for the evolution of a shared national identity.

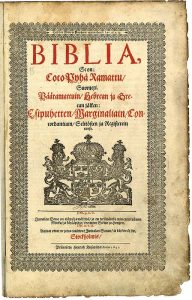

Biblia

The first leaf of the Biblia, the Finnish translation of the entire Bible from 1642. Wikimedia Commons

The Finnish New Testament was published in 1548 by Mikael Agricola, but subsequently almost a hundred years passed before the entire Bible was published in Finnish. The “Biblia”, or the “whole Saint Bible in Finnish”, was published in 1642. A thanksgiving service was organised in Finland to commemorate this historical event. The Bible was dedicated to the Swedish Queen Christina, who somewhat ironically had converted to Catholicism only twelve years later. The Biblia was a very important step for the Finnish written language, creating what can be called a standard, unified language for Finland.

Leave a Reply