The Baltic Carrier Accident in 2001 (part 1/4): What Happened and Who Were There

Large-scale oil spill disasters are – luckily – relatively rare. But when they do happen, the existing knowledge, skills, and procedures are activated and tested. In the best case, lessons learned from the previous incidents are the foundation for the next response. In this four-part blog series, Kia Friis Petersen from the Danish Civil Protection League takes us back to 2001 when Denmark’s largest oil spill accident occurred. Part 2, 3 and 4 of this blog series can be accessed here.

Written by Kia Friis Petersen, Danish Civil Protection League

Introduction

On the 29th of March 2001 at 00.20 o’clock, the Admiral Danish Fleet (ADF) received an alarm stating that the oil tanker ‘Baltic Carrier’ and freight ship ‘Tern’ had collided south of Falster, Denmark. Shortly after, the report included oil leaking from ‘Baltic Carrier’, which had a total of 33,000 tonnes of heavy fuel oil in the cargo. And thus, the great operation had begun.

In this small series of articles, we will dive into the details of the operation of the ‘Baltic Carrier’. You will get to know more about the challenges and victories, how the many organisations managed to cooperate and collect the oil. The articles are primarily based on the Danish evaluation report created by the Danish Emergency Management Agency (DEMA) and an interview with a key person who participated in the operation, Peter Søe, Chief Fire Officer at Lolland-Falster Fire and Rescue Service.

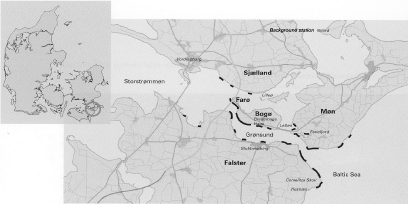

In 2001 Søe was in the Danish Emergency Management Agency, working at the National Fire and Rescue Centre in Naestved (DEMA SJ). When the two ships collided, he was stationed at the island Faroe as incident commander for the operation on land. Søe was in charge of the coordination and logistics of all the personnel working on the shores in and around the belt of Groensund.

“The worst oil catastrophe in Danish history happened the 28th of March 2001, when 2,700 tonnes oil leaked into the ocean by the South sea islands. The two ships Baltic Carrier and Tern had collided in the Kadetrende, the western entry to the Baltic Sea. The collision and weather condition resulted in the Baltic Carrier leaking 2,700 tonnes of oil of which most were washed up on the shores of especially Moen and Bogoe.

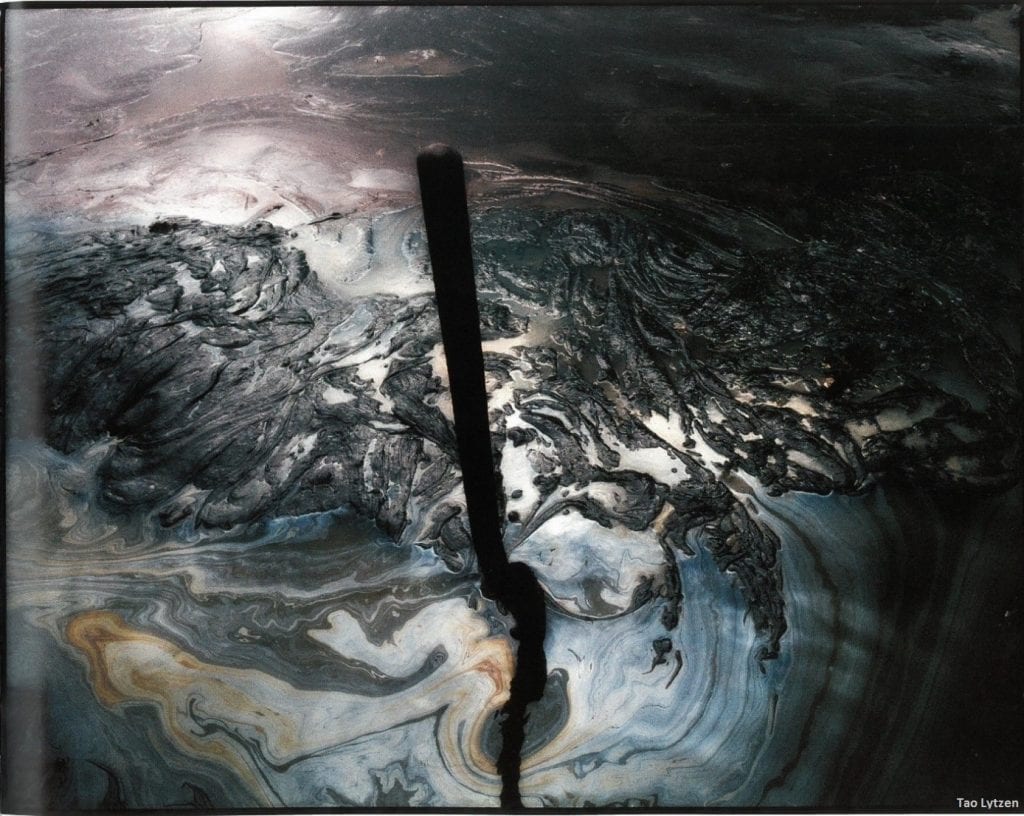

At arrival to the coast I was first met by the stank of oil, that stung in my nose. Thereafter the unforgettable view of the tremendous amount of oil, which lay as a thick, black, liquorice-ish mass in the ocean, along the coast, and in the beach planting. The catastrophe was obvious to anyone. It was clear that a great cleaning operation was waiting up ahead, and it would take months before the cleaning was ended.

The silence and peace that normally characterised the islands were interrupted by a traffic of DEMA personnel, environment experts, volunteers, Home Guard people, police, reporters, and worried islanders. Along the coast they all worked side by side. Working by hand, shovels and spades were in many places their only tools, as the terrain was rugged, and as these tools were most careful of the nature. The sound of entrepreneur machines was heard in the background and with frequent intervals shots sounded. Merciful shots that liberated thousands of birds from sufferings, after their plumage had been smeared with oil.” – Photographer Tao Lytzen, 2001.

Collision in the middle of the night

The two ships collided in the middle of the night, and shortly after the ADF launched an operation to contain the oil. However due to severe weather conditions it was not possible to contain the oil on open water. And in the late afternoon of the 29 March the oil drifted into the belt Groensund between the islands of Moen and Falster. In total 2700 tonnes of heavy fuel oil leaked from Baltic Carrier and about 2350 tonnes entered Groensund. The oil hit several smaller islands and along the coasts of Moen and Falster, making the operation even more difficult.

There were many actors participating in the operation. It was led by the ADF under the Danish Ministry of Defence, who by law is the responsible actor for managing oil pollution on open sea and shallow waters cf. Danish Act for the Protection of the Marine Environment. As the collision happened near the German Exclusive Ecological Zone, two German environment units were sent to help, but as the oil drifted into Danish waters, the Danish authorities were in charge of the operation. Further the ADF asked Sweden for assistance, who sent an environment unit. Both Germany and Sweden provided environment surveillance planes as well. On the national front, five municipalities and their fire and rescue services were activated as well as the County of Storstroem. DEMA and the Danish Naval Home Guard participated with both personnel and equipment and the Police helped with the coordination. Besides all the authorities, volunteers and private entrepreneurs assisted in the operation.

Phases of the operation

The operation can be divided into three phases: the alarm phase, the rescue operation on land and sea, and the afterward clean-up.

Alarm phase: In the first few hours after the initial alarm call, ADF establish a 24-hour service and activated the national maritime environmental response, including four oil recovery vessels from the Royal Danish Navy, the local police, municipalities and their local fire and rescue services, and DEMA.

Rescue operation

- Initial response: At 00.40 o’clock the German authorities notified ADF, saying they had sent environment units to the collision site, and about 30 minutes later they notified all ship traffic in the area. The German units were the first on scene at around 2 in the morning. They began an oil collecting operation at sea but had to give up due to the weather conditions with high sea and strong wind. The first two of the Danish oil recovery vessels arrived at 11.00 and 12.00 o’clock. They tried to contain the oil with booms but had to give up as the German units. One ship tried to stop the oil from drifting into Groensund but due to the amount and type of oil the ship’s engine cut out.

- Response on sea: As the operations to contain and collect the oil near the Baltic Carrier failed during 29 March the various units set up oil booms as barrages in the harbours and other areas which were threatened to be hit by the oil. On 30 March they could start collecting the oil in Groensund, where it lay in big pools near the coasts. In total 1,100 tonnes of oil were collected at open water by Danish, German, and Swedish environment units in the period from 29 March until 10 April.

- Response in shallow waters: With the high viscosity the heavy fuel oil had the texture of liquid asphalt making most of the equipment not applicable, including skimmers normally used in shallow waters. Instead private entrepreneurs were hired to grab or shovel the oil up with diggers. At the same time smaller booms were used to drag the oil to the diggers and to avoid it to drift into clean areas. However, it was not possible to use the diggers in all contaminated areas, as there were no roads, or the ground was to soft. In these areas the oil had to be removed manually. In total 2,800 tonnes of oil and oil contaminated materials were collected in shallow waters during the operation. “I had around 350 people working when we peaked” says Peter Søe. “Most of them from DEMA, both conscripts and officers, but also from the Danish Home Guard, volunteers and private entrepreneurs… They worked ten to twelve hours a day in all types of weather”.

Clean-up on coastal areas: In most of the coastal areas the actual clean-up did not start until 11April, as the oil in the shallow waters had to be removed beforehand. In the first days from the 11th the main task for the municipalities included cleaning, surveillance of the shores and taking calls from civilians who had observed more oil. The clean-up operation was done manually in many areas, some places with help from local entrepreneurs. The cleaning was carried out by the municipalities’ Technical and Environmental administration units, local fire and rescue service’s volunteers, local entrepreneurs, private persons, and several private organisations. Greenpeace also sent a ship to the area and participated in the clean-up at the island Malurtholm. In total, around 10,750 tonnes of oil and oil contaminated material were collected until the end of July 2001.

The use of volunteers

The fire and rescue service volunteers that participated in the operation came from municipalities all around Denmark – some travelled almost 400 km just to help. “During the 1990’s many of the local fire and rescue services had shot down their volunteer units along with the war preparedness after the fall of the Berlin Wall. So, there weren’t many volunteers to draw upon in the area” – Peter Søe. The volunteers had the same education as the firefighters and could therefore easily join the clean-up operation on shore. Other organised volunteers who participated came from the Army Home Guard and Police Home Guard. At sea, the volunteers primarily consisted of the Naval Home Guard who assisted the Navy.

Spontaneous volunteers from far and wide wanted to help in the cleaning operation. However, there were several issues related to this as Peter Søe explains: “We had strict rules regarding personal hygiene, as the oil could pose a health risk if it got in contact with the skin or were ingested. So, they need instructions and personal protection equipment. It was also an issue to ensure that the spontaneous volunteers could work together in teams under a type of management they were not used to. A third problem was lodging of the volunteers. And the fourth issue was planning and logistics. It wasn’t sure that spontaneous volunteers would show up the next day or the day after, when they had been doing physically hard work for twelve hours straight. So, all spontaneous volunteers were sent away, as we did not have the resources to educate and manage them. And there was the question of insurance. We underlined that it wasn’t because we couldn’t use their help, we just didn’t have the resources.”

The spontaneous volunteers had a high commitment and a will to participate in the long, hard, and filthy work, but unfortunately, they were not allowed to help as it was too big a task for the authorities to handle. Instead the organised volunteers and authorities worked tirelessly for days and months, from early morning to late evening to contain and collect the oil from the greatest oil spill in Danish history.

Sources:

- DEMA, Development unit (2001). Bekæmpelse af olieforureningen efter “Baltic Carrier” – En tværgående evaluering og erfaringsopsamling.

- Danish Act for the Protection of the Marine Environment

- Peter Søe, Chief Fire Officer at Lolland-Falster Fire and Rescue Service (2020), interview.

- Tao Lytzen (2001). Olie – Et fotografisk essay om oliekatastrofen på sydhavsøerne, Ergo.

Leave a Reply