Jaakko Dickman

This blog post was produced as part of the course “Social Media, Ideologies, and Ethics in the United States” at the University of Turku.

Is Facebook

simply a platform that neutrally mediates decentralized information created by

its users or is it something closer to a publishing company? This issue has

been central to the debate on the need to regulate Facebook and other social

networking sites.

The debate

has further intensified after the reported Russian interference in the 2016 U.S.

Presidential Election and after the live streaming of the Christchurch mosque

shootings. Actor-comedian Sacha Baron Cohen is the latest to criticize Facebook

and offer his thoughts on the issue.

In his

award speech for the ADL International Leadership Award, Cohen strongly

criticized social networking sites (SNSs) for compromising democratic ideals

and promoting hate and violence. He stated that “on the internet, everything

can appear equally legitimate” and that this is dismantling our understanding

of shared objective facts that are fundamental to a functioning democracy.

Cohen concluded his speech by declaring that “it is time to finally call these

companies what they really are: largest publishers in history.”[i]

At the

heart of Cohen’s speech is the idea that SNSs “should abide by basic standards

and practices,”[ii]

as do traditional media outlets such as newspapers and TV news. Thus, they

should be considered as publishers. To this day, SNSs have evaded

responsibility over their content by stating that they are simply platforms that

mediate content and thus not liable for the content they host. This indemnity

is solidified by the US Communications Act of 1996, which gave an almost

complete autonomy for SNSs to regulate themselves (Flew & al 2019, 38).

However, one could argue that the nature of networked communication has changed so drastically that the new SNSs have outgrown the legislation. Furthermore, the growing interference and curatorial work done by the SNSs has made their ‘neutral platform’ nature questionable.

It is

obvious that Facebook, among other SNSs, is not a neutral mediator of networked

communication. One of the clearest examples of this came in 2016 when Facebook’s

“Trending Review Guidelines” were leaked to the press. The guidelines revealed

how Facebook’s news operation is perpetrated by human intervention similar to

traditional media organizations.[iii]

Still, we have seen that the self-regulative practices of SNSs have not been

effective enough to tackle the spreading of violence, hate speech, and

political interference.

Without acknowledging the new pressures to

regulate these sites in a new cultural, political, societal, and technological

environment, these companies will not be held accountable for their

shortcomings. So, what is holding us back from insisting that these sites are,

in fact, publishers of content and from enforcing governmental regulation on

them?

Nowadays,

when social media companies are operating globally, nation-specific regulation

might cause SNSs such as Facebook to become scattered, with different content

available in different parts of the world. Flew, Martin, and Suzor state that

this type of a “global Splinternet” might have a negative impact on the free

flow of information that has epitomized the period after mid-1990s (Flew &

al., 46). As asserted by the CEO of Facebook Mark Zuckerberg in his speech at

Georgetown University, social media has become “the Fifth Estate” that allows

people all over the world to express themselves.[iv]

The power to give voice to people living under brutal political regimes is a

feature that we do not want to take away from SNSs.

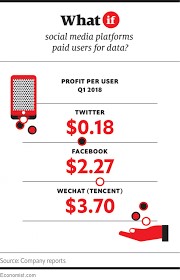

Presently,

the biggest internet companies are regulating the flow of information unelected

and without accountability. According to Cohen, this constitutes ideological

imperialism.[v] The

more SNSs take part in “monitoring, regulating and deleting content” the more

dire is the need for public accountability (Flew & al., 45). However,

instead of traditional nation-specific legislature, the ability to regulate

this new digital environment seems to call for active involvement of global

regulative bodies. Nevertheless, the new role of SNSs and their power to

dictate the flow of information requires new regulative approaches and ideas as

their counterforce.

Bibliography:

Anti-Defamation

League YouTube, ADL International Leadership Award Presented to Sacha Baron

Cohen at Never Is Now 2019, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ymaWq5yZIYM&t=24s> (Accessed Dec 8th 2019)

Flew,

Terry, Martin, Fiona, & Suzor, Nicolas (2019) “Internet Regulation As

Media Policy: Rethinking the Question of Digital Communication Platform

Governance.” Journal of Digital Media & Policy 10, no. 1: 33, 33–50.

Thielman,

Sam (2016) ”Facebook news selection is in hands

of editors not algorithms, documents show.” The Guardian. <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/may/12/facebook-trending-news-leaked-documents-editor-guidelines> (Accessed Dec 8th 2019)

Washington

Post YouTube, Watch live: Facebook CEO Zuckerberg speaks at Georgetown

University, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2MTpd7YOnyU&t=2777s> (Accessed Dec 8th 2019)

[i] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ymaWq5yZIYM&t=20s

[ii] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ymaWq5yZIYM&t=20s

[iii] https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/may/12/facebook-trending-news-leaked-documents-editor-guidelines

[iv] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2MTpd7YOnyU&t=2777s

[v] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ymaWq5yZIYM&t=20s