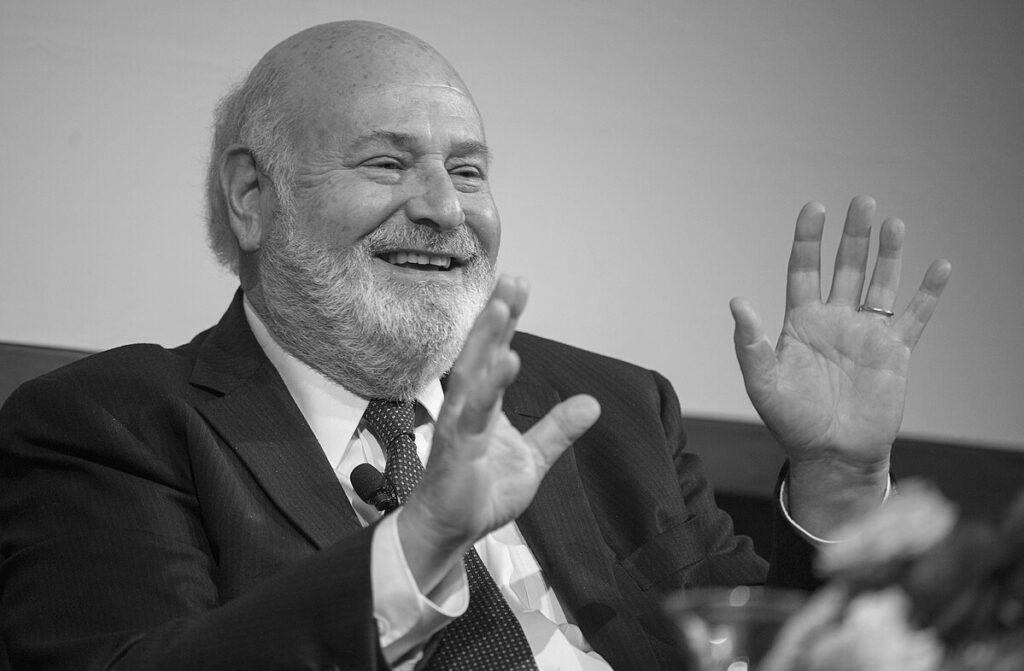

On Monday, I awoke to the news that director, actor, and political activist Rob Reiner and his wife, photographer and producer Michele Singer Reiner, had been killed in their home. Reiner became famous for his role as Michael Stivic on television’s All in the Family in the 1970s, established himself as one of the most respected directors in the 1980s with masterpieces such as This Is Spinal Tap, The Princess Bride, and Stand by Me, and turned his fame and money into political activism fighting against the tobacco industry, for children’s education, and leading the charge for same-sex marriage in California and nationally.

Rob Reiner: I'm going to make a coming of age drama, a fantasy adventure story, a romantic comedy, a psychological horror and then a courtroom drama.Us: Across your entire career?Reiner: In a 6 year period. Us: That sounds-Reiner: -Each one will be arguably the best movie in that genre.

— Richy Craven (@richycraven.bsky.social) 2025-12-15T08:04:08.202Z

The tragedy left me with a deeper sense of unease than I expected. I have spent the past decade researching the television show on which Reiner made his name and the political activism at which Reiner excelled.

No, I didn’t lose a friend. In fact, I never met Reiner. But I have listened to countless hours of oral histories and interviews with him, read an endless number of articles about his work, and watched and re-watched him on the screen more times than I can count. So yes, I did lose somebody. You do form some kind of relationship with the people you study – even if we seldom talk enough about that connection.

Rob Reiner at an event at the LBJ Presidential Library in 2016.

Most historians have the reassuring knowledge that their cast of characters are dead and buried long ago. It’s easier, in a certain sense, to riffle through somebody’s private letters or secret diary when you know that they are no longer around. Sometimes, I can feel a sense of envy towards my colleagues specializing in ancient Greece, medieval monasteries, or early modern nobility.

The ethical considerations are different when you know that the people you study, and their family, are still among us. The responsibilities are also different. The subtitle of Claire Bond Potter and Renee C. Romano’s edited collection on Doing Recent History begins to capture the challenges inherent in the field: On Privacy, Copyright, Video Games, Institutional Review Boards, Activist Scholarship, and History That Talks Back. There is not, however, a chapter on what happens when a central figure in your research passes away.

I began thinking about these questions more around two years ago, when producer Norman Lear passed away at age 101. Lear is the central figure in my first monograph. When doing the research, I met with Lear, interviewed him on two occasions, and received access to his private archive. I have close friends I have spent less time with than the total number of hours I used reading Lear’s letters, listening to him talk about his work and life, reading about him in everything from the New York Times to Playboy (yes, they are digitized and available on Internet Archives), and laughing at his stories on Johnny Carson, David Letterman, and Jimmy Kimmel.

It’s not exactly a parasocial relationship, the historian is not a fan and the archives are not mass mediated. But it is often a one-sided and non-reciprocal bond that is formed in the archive. Both Lear and Reiner were kind and decent people looking to make people laugh while working to make the world a better place, but this isn’t about idolization. I have colleagues who recognize a similar bond with the most vile and objectionable figures imaginable. I think this is about storytelling. The people you study are also the characters in your story.

Novelists often talk about their fictional characters as real and beloved friends or even as their children. An article in the Atlantic, from 1887, on the subject notes that “[e]ven the elder Dumas, whose stories were made up of adventure and intrigue, with only here and there an attempt at portraiture, would shed tears over the memory of his genial giant, Porthos.” More recently, a study at the Edinburgh international book festival found that over 60% of authors could hear their characters speak or viewed them as capable of acting independently. Crime novelist Val McDermid, for example, acknowledged that “when I’m working on a novel, I have conversations in my head with them.”

Academic writing is, of course, different. Scholars cannot form the characters through imaginative conversations. We are limited by the historical record and the ethical and methodological considerations of our disciplines. This also means we have no control over the actions or fates of our characters.

Based on the number of messages I received from fellow historians after the tragic news of Reiner’s death, there is a wide recognition of the connection between scholar and the subject of the study even if none of my colleagues could find the right words to describe it. An “unsettling feeling” is the closest I have come to a definition.

I recognize, of course, that the tragic death of Reiner is distinct in 1) his celebrity, 2) the violent nature of his death, and 3) the cruel reaction by the president of the United States to the news. Still, I would welcome further conversations on the general subject of how to cope with the passing of a figure you study and, in particular, I want to hear experiences from scholars in other fields (for example literature, media studies, or sociology) on this sensation.

It should, perhaps, surprise no one that I turned to the trade of the historian to process my own thinking and feelings – going back to the sources (including revisiting some of his oral history interviews and re-watching Reiner in an episode of All in the Family and screening his directorial masterpiece A Few Good Men), talking with colleagues, and writing down my thoughts. That’s what historians do.