How children feel when they witness bullying effects whether they defend victims

Jessica Trach

INVEST Blog 3/2020

It is important for children to feel safe at school so that they can learn the essential academic and social skills needed to become healthy and productive members of society. Several decades of research on school bullying has shown that experiencing peer victimization during childhood adversely impacts children’s current well-being, and can have serious, long-lasting consequences for victims (McDougall & Vaillancourt, 2015). In addition, witnessing bullying at school has been shown to negatively affect bystanders’ mental health and well-being (Rivers et al., 2009). As such, bullying is an important problem that must be addressed and prevented to ensure that all children are able to achieve their full potential in life.

One way to prevent bullying from getting worse is to empower children to intervene when they see their classmates being mistreated. Many schools use anti-bullying programs like the KiVa program (KiVA Koulu), developed at the University of Turku by Dr. Christina Salmivalli and colleagues (2011) to teach children to have empathy for victims of bullying, and the coping skills to successfully defend them (among other things). Since bullying almost always happens in front of other children (O’Connell, Pepler, & Craig, 1999), it is necessary to understand how children’s relationships with the bully, the victim, and with other witnesses influence how and when they choose to help. By gathering more information about these bullying group processes, we can improve our current anti-bullying interventions to make them even more effective.

It has been suggested that children are more likely to defend when they are friends with the victim, and that victim’s friends use both prosocial strategies (such as telling an adult or comforting the victim), and hostile-aggressive strategies (for example, seeking revenge). However, when children are friends with the bully they may also be more likely to join in and support the bullying, making things even worse for the victim. It is also reasonable to expect that children’s reactions as bystanders would be related to the emotions they feel when they see someone being bullied. For example, children who feel very afraid may want to avoid a direct confrontation with the bully. In contrast, children who feel guilt or anger may be more likely to defend the victim (e.g., Pozzoli, Gini & Thornberg, 2017).

At present, we know very little about how different emotions are evoked in different situations – for example, when the victim is a close friend versus a stranger. We also do not know if the emotions that bystanders feel while witnessing bullying are related to specific types of defending strategies. This study tried to answer these questions by examining the bystander strategies that children reported using based on their emotional reactions to a specific, real-life case of bullying that they had recently witnessed at school. We also investigated whether the strategies they used as a bystander depended on their relationship with the bully and the victim.

For this research study, a sample of 2,513 Canadian children (approximately 9-13 years old, 52% girls) completed a survey where they were asked how often they witnessed bullying at school. A total of 89% of the students reported that they had witnessed someone else being bullied at least once during the current school year. The children who had witnessed bullying were then asked to remember a specific case where they had seen another student being bullied, and to describe who was involved and how they felt about the situation. Specifically, children were asked to report whether they knew either the bully or the victim, and if they knew them whether or not they liked this person. Regarding emotions, children could choose one of six feelings to describe how they felt about the bullying: happy, sad, scared, guilty, angry, or nothing (indifferent). Finally, children were asked how they responded to the situation using a variety of strategies, such as helping the victim, telling an adult, telling the bully to stop, hurting the bully, joining in with the bullying, laughing and watching the bullying, and not getting involved.

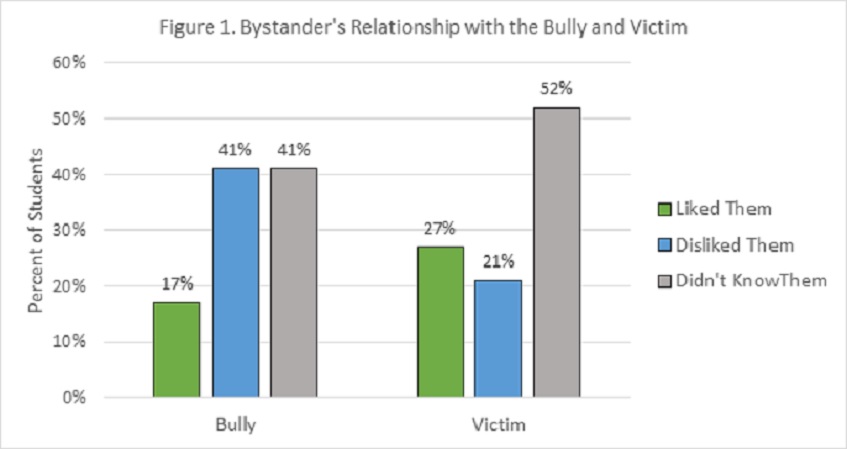

Figure 1 shows the relationships that children described having with the bullies and victims. In this study, the participants tended to recall a case where they didn’t know either of the other children involved. However, follow-up statistical analyses indicated that in situations where bystanders liked the victim they were also more likely to know the bully, and in cases where the bystanders liked the bully they tended to dislike the victim.

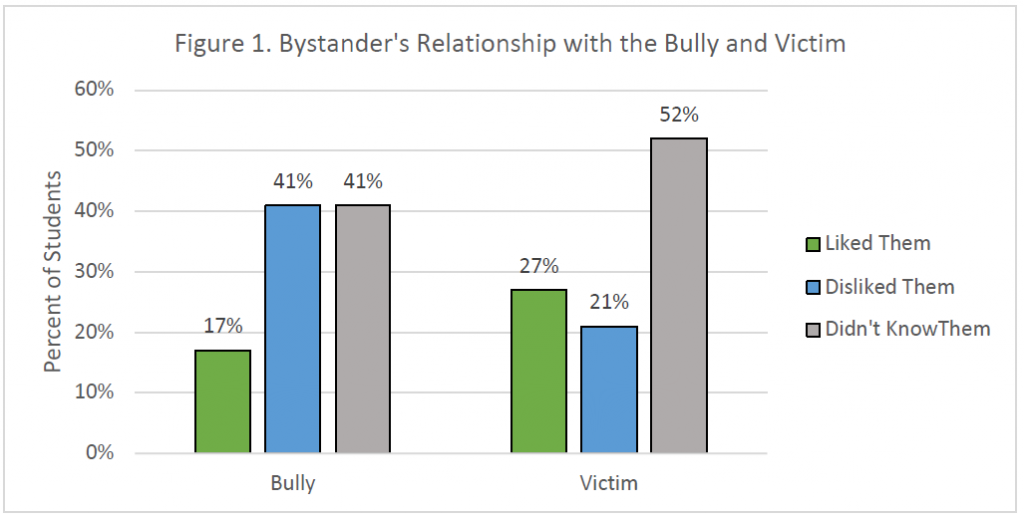

Figure 2 shows the emotion that children used to describe how they felt while they were witnessing a specific case of bullying. Somewhat surprisingly, when asked to choose a single emotion, more children reported feeling angry, compared to sad or scared. Very few children reported feeling happy about the bullying they saw, although almost 20% reported feeling neutral or indifferent. These results indicate that although most children feel upset when they see bullying, there are still quite a few who have a suppressed emotional reaction, perhaps indicating a lack of empathy for the victim. Another way of describing this reaction is moral disengagement, which is a cognitive process that allows people to emotionally and morally detach from upsetting situations as a way of protecting themselves. Next, we looked at whether these children’s emotional reactions were connected to their relationships with the bully and victim.

Next, we compared the emotional reactions of bystanders depending on whether they knew the other children involved. We found that older students and boys were less likely to report feeling scared and more likely to report feeling nothing about the bullying they witnessed compared to younger students and girls. Feeling happy was also more common among younger students compared to older students, and girls were more likely to say they felt sad than boys.

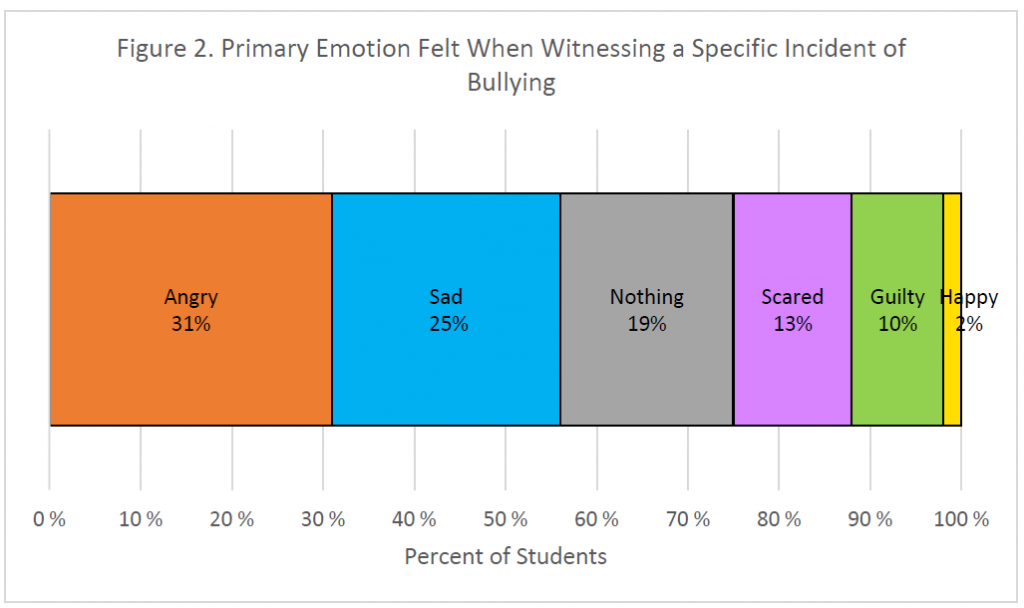

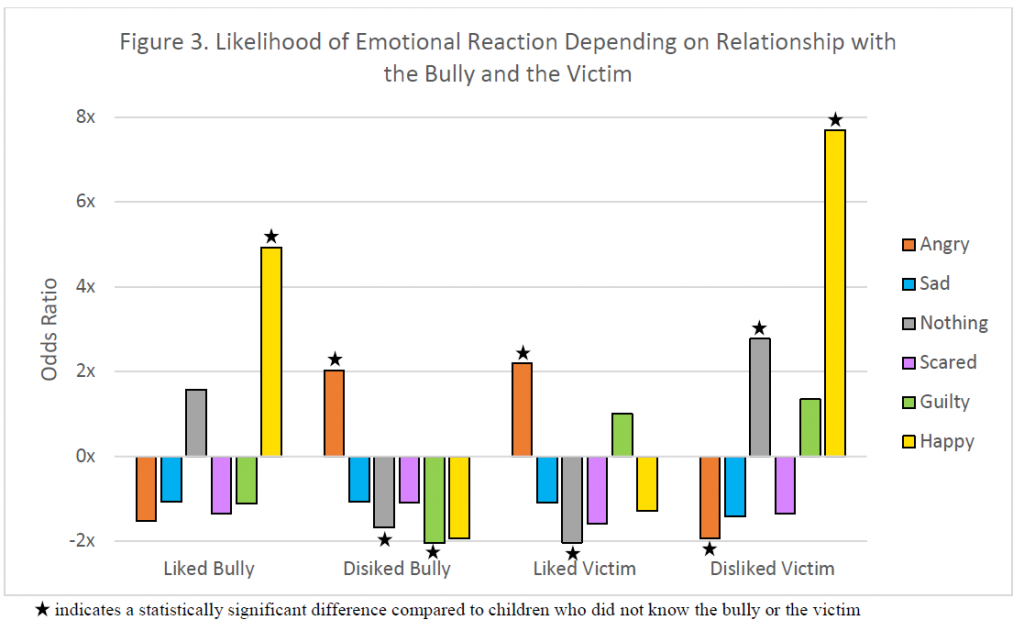

After controlling for grade and gender differences, statistically significant patterns emerged regarding children’s relationships with the bully and the victim and the emotions they felt while witnessing a bullying incident (Figure 3). Children who liked the bully were almost 5 times more likely to feel happy about the situation compared to students who didn’t know the bully. In contrast, children who disliked the bully or liked the victim were 2 times more likely to feel angry about what they witnessed. Finally, children who disliked the victim were nearly 8 times more likely to feel happy about the bullying and 2 times less likely to feel angry compared to children who didn’t know the victim.

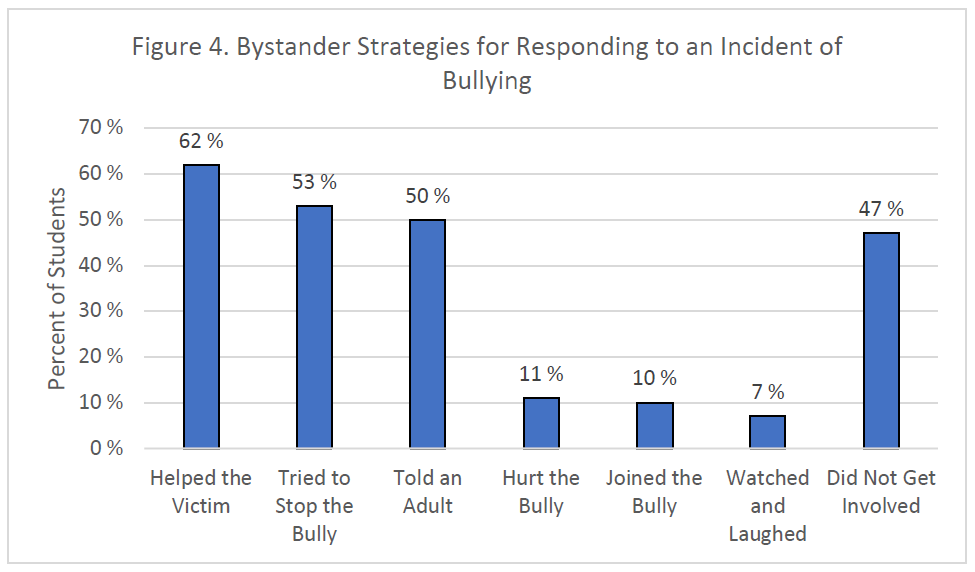

Lastly, we wanted to explore how children’s emotional reactions and social relationships impacted their behaviour as bystanders. Figure 4 shows the frequency of each type of bystander strategy that children said they used to respond to the bullying incident. On average, children reported using 3 different types of bystander strategies to respond to one incident of bullying. Over half of the students reported that they tried to defend the victim by helping them or telling the bully to stop. A small minority of bystanders (11%) reported retaliating against the bully using aggressive behavior to try to hurt them. It was less common for children to recall a situation where they joined in the bullying or supported the bully by watching and laughing. Almost half of the students in this sample reported that they chose not to get involved when they saw another student being bullied. These results are consistent with previous research on this topic (e.g., Trach, Hymel, Waterhouse, & Neale, 2010).

Compared to younger students, older children were less likely to say that they joined the bully or told an adult about the bullying incident. Boys were more likely to report that they tried to stop the bully or hurt the bully, but also that they watched and laughed more compared to girls.

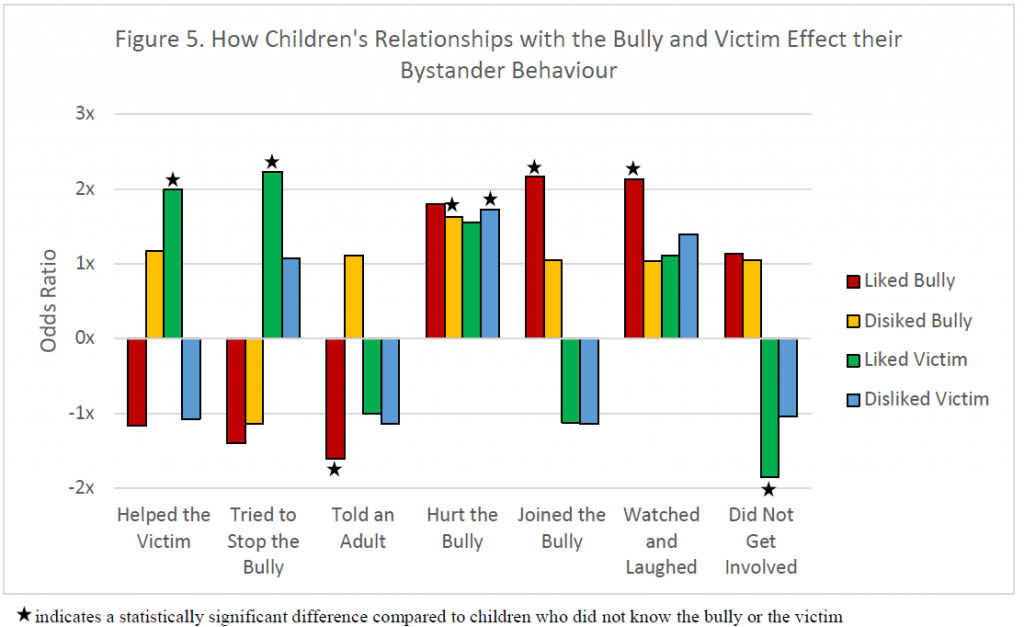

After controlling for grade and gender differences, we found that whether or not children acted as a defender did depend, in part, on their relationship with the other children involved. Specifically, their bystander strategies differed depending on whether they liked the victim or the bully. As shown in Figure 5, children who liked the victim were 2x more likely to say that they tried to help the victim, or stop the bully, and were significantly less likely to avoid getting involved (also known as being a passive bystander). On the other hand, children who liked the bully were 2x more likely to join in the bullying or watch and laugh, and were also significantly less likely to tell an adult about the bullying they witnessed.

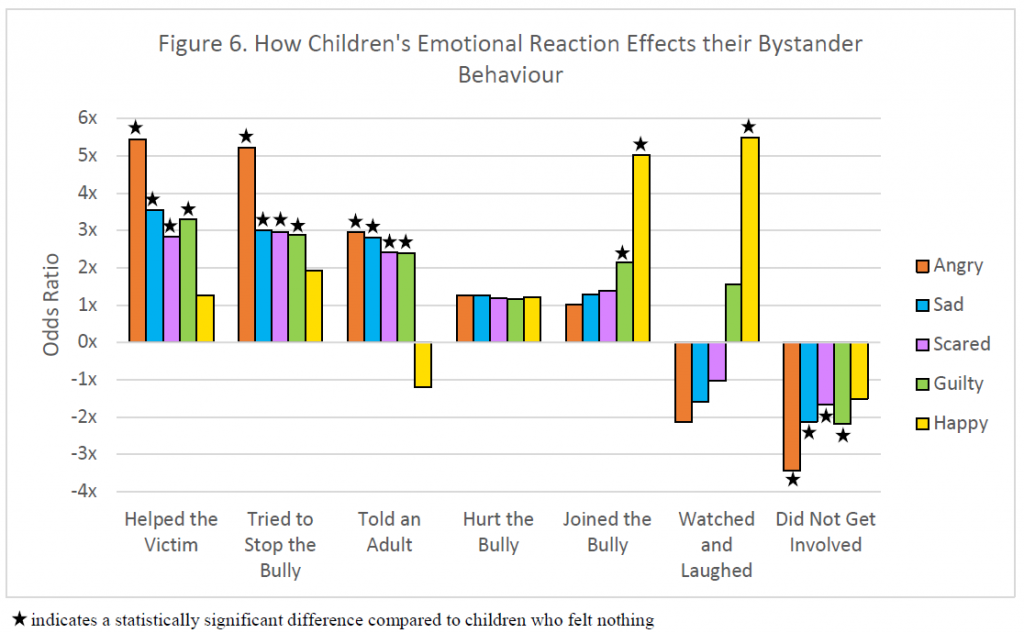

Figure 6 illustrates the relationship between children’s emotions and bystander strategies. The main finding here was that children who reported feeling angry about the bullying incident were over 5x more likely to try to help the victim compared to children who felt nothing about the situation. Feeling sad, scared or guilty were also positively related to defending the victim, although children who joined the bully were also more likely to say they felt guilty compared to those who felt nothing. Finally, children who felt happy about the bullying were 5x more likely to say that they supported the bully by joining in or watching and laughing.

Key take-aways from this research study:

- Most children felt upset when they witnessed bullying at school, and feeling any negative emotion significantly decreased the odds that children remained passive when they saw another child being bullied

- Anger was the most common emotion

reported by children when they witnessed bullying at school, especially if they

liked the victim or disliked the bully.

- Bystanders were significantly more likely to defend the victim if they liked the victim (2x more likely) or felt angry about the situation (5x more likely)

- Very few children felt happy when they saw another student being bullied, but it was more common among children who said that they liked the bully or disliked the victim

- Bystanders were significantly more likely to support the bully if they liked the bully (2x more likely) or felt happy about the incident (5x more likely)

- Children who joined in the bullying were also more likely to report feeling guilty about the situation – possibly because they felt bad after they joined in

These results have several important implications for anti-bullying intervention programs.

First, this study confirmed that children’s responses as witnesses to school bullying are influenced by their relationship with the bully and the victim. Specifically, bystanders are inclined to protect the person they like, even if that person is behaving badly (e.g., the bully). Therefore, it is important that anti-bullying efforts include a component that promotes group norms against bullying to reduce the chances of peer victimization. It is also important to help children understand the negative consequences of bullying for everyone involved, including bullies and witnesses.

At the same time, youth need opportunities to learn from their actions to develop healthier ways of relating to others. It is very important that schools adopt clear consequences for bullying, and that these consequences are communicated to all students before an incident occurs. Given the complexities of the group dynamics involved in bullying, it is also important that disciplinary consequences for bullying take a restorative approach that provides opportunities for youth to repair the harm caused by their actions and restore their position in the group. For this approach to be effective, adults also need training and support to be able to identify incidents of bullying early and respond swiftly to minimize any further chance of harm to those involved.

Finally, anger appears to be an important motivator for defending victims of bullying. Anti-bullying programs that specifically teach strategies for constructively managing feelings of anger may help to increase rates of defending among youth. Similarly, emotional literacy and emotion regulation skills may be especially important for children who are inclined to morally disengage when they witness bullying. Being able to label their emotions and understand their feelings in reaction to different situations may be helpful for transforming passive bystanders into active defenders.

Original publication

Trach, Jessica & Hymel, Shelley (2020) Bystanders’ affect toward bully and victim as predictors of helping and non‐helping behaviour. Scandinavian journal of psychology, 61(1), 30-37.

Author biographies:

Jessica Trach is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Psychology at the University of Turku with the ‘Inequalities, Interventions, and New Welfare State’ (INVEST) Research Flagship.

References

McDougall, P. & Vaillancourt, T. (2015). Long-term adult outcomes of peer victimization in childhood and adolescence: Pathways to adjustment and maladjustment. American Psychologist, 70, 300-310.

O’Connell, P., Pepler, D., & Craig, W. (1999). Peer involvement in bullying: Insights and challenges for intervention. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 437–452.

Pozzoli, T., Gini, G. & Thornberg, R. (2017). Getting angry matters: Going beyond perspective taking and empathic concern to understand bystanders’ behavior in bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 61, 87–95.

Rivers, I., Poteat, V., Noret, N., & Ashurst, N. (2009). Observing bullying at school: The mental health implications of witness status. School Psychology Quarterly, 24, 211-223.

Salmivalli, C., Kärnä, A. & Poskiparta, E. (2011). Counteracting bullying in Finland: The KiVa program and its effects on different forms of being bullied. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35, 405–411.

Trach, J., Hymel, S., Waterhouse, T. & Neale, K. (2010). Bystander responses to school bullying: A cross-sectional investigation of grade and sex differences. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 25, 114–130.