Mothers miss out – Limited adult education opportunities in the context of scarce public support

Heta Pöyliö & Patricia McMullin

Formal adult education can advance gender equality by boosting female employment and addressing women’s labor market disadvantages. Policies supporting adult education and work-family balance can help mothers overcome barriers to pursuing their learning goals. In order for the Finnish economy to maintain a sustainable labour force, the opportunities to adapt to the changing work and family situations should be guaranteed to everyone.

Bridging the gap: Adult education’s role in solving current and future labour market challenges

Adult education has long been seen as a key strategy in European welfare states to support the workforce in adapting to the changing skill requirements of the digital transition as well as tackling unemployment and investing in the human capital of a society. More recently, as the working age population declines in many countries, it has become even more important to invest in the resilience of the labor force by promoting the inclusion of groups that may otherwise lack the resources or skills to participate fully in the workforce.

Particularly in the form of formal adult education, that provides new or higher educational qualifications, individuals are able to aim for better employment prospects. Prior research has highlighted formal adult education’s positive impact on earnings (Stenberg, 2010; Triventi and Barone, 2014), job prestige (McMullin & Kilpi-Jakonen, 2014), and stable employment (Vono de Vilhena et al., 2016).

Participation in formal adult education is among the highest in the Nordic countries (Eurostat, 2020), where the welfare state overall aims at supporting families and disadvantaged groups. In these contexts, adult education is often aimed at promoting labour market attainment and employment of low-skilled or otherwise marginalized populations (Stenberg 2010; Vono de Vilhena et al., 2016). In liberal welfare states, such as Great Britain, on the other hand, households receive much more limited public support for adult education, yet participation rates match or exceed those in Northern Europe.

A study on unequal adult education opportunities: How family constraints shape learning opportunities in two different systems

A new study by Pöyliö and McMullin asks whether the opportunities to participate in formal adult education are equally distributed among the population and in particular for families with lower financial resources? By studying two almost opposite systems of adult education, Finland and Great Britain, one of the core findings of the paper is that strong support for families relieves resource constraints to participation in formal adult education. The gap in the chances of enrolling between different family types and gender is smaller in Finland than in Great Britain.

Lack of time and resources due to work and family responsibilities are often reported as the main reasons for not participating in adult education (Stoilova et al., 2023). Although women would gain higher returns to the new educational qualifications obtained, Pöyliö and McMullin found that family responsibilities are more likely to restrict the participation of women than men. This is particularly evident in Great Britain, where family situation does not impact men’s chances to participate in formal adult education.

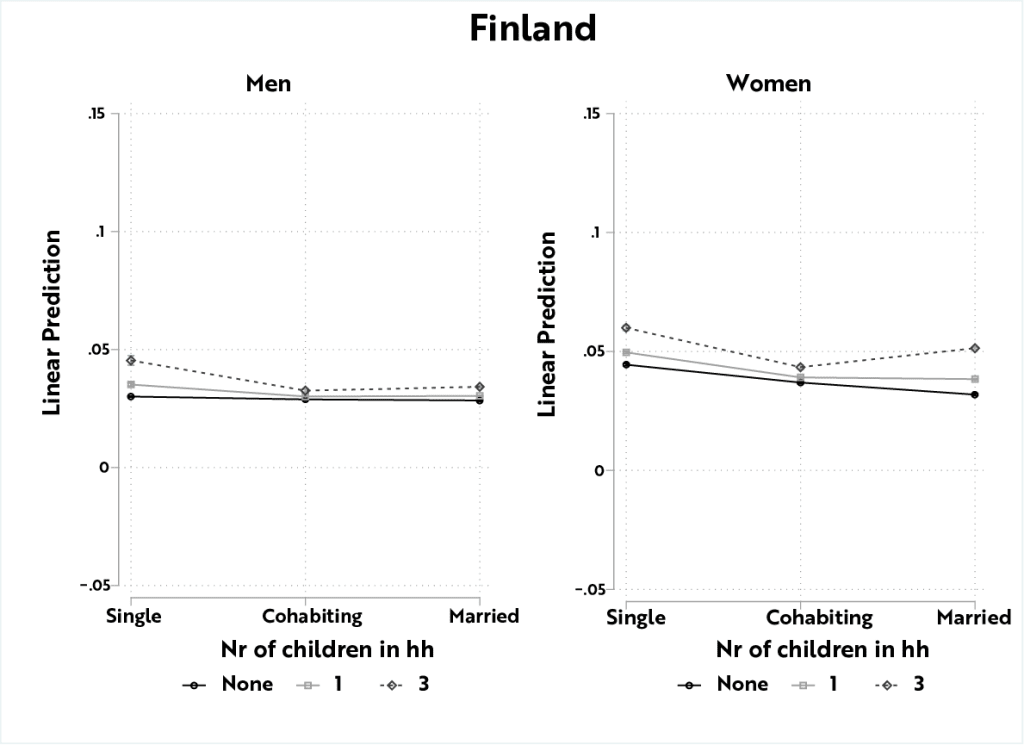

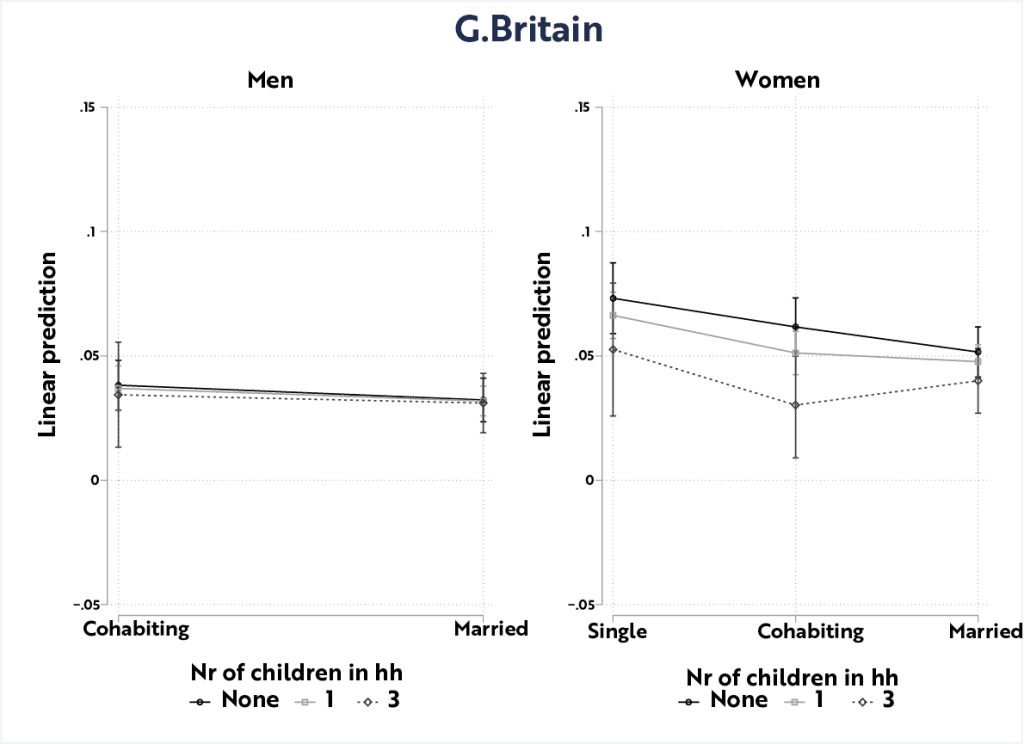

Family situations with increased time and resource demands on parents, such as being a single parent, when children are young or there are many children in the household, all lowered the likelihood to participate in formal adult education among women in the United Kingdom, but less evidently in Finland (Figure 1). On the contrary, Finnish single mothers had a similar likelihood to enrol than other family groups, and women with multiple children had somewhat higher likelihood to participate in adult education.

Participation in formal adult education across family status and number of children in Finland and Great Britain

Public support is key in providing equal chances for labour market adaptation

One reason for the different results could be the available public support in these two countries. The United Kingdom follows many other countries in Europe in providing none or very scarce financial support to participate in adult education, despite international initiatives to increase LLL programmes and the equal access to them (European Commission, 2023). The Finnish system of adult education which provided an allowance and guaranteed study leaves from employment in this period was comparatively unique in its comprehensiveness. The adult education allowance was mostly taken up by women and over third of the allowances were used to obtain qualifications in social and health services, a sector that is struggling with adequate amount of workforce (Työllisyysrahasto, 2024). This year the government has, however, decided to abolish the adult education allowance. Inevitably, this will alter the chances to participate in adult education, particularly in formal education where the allowance was targeted.

Following the recent cut in adult education allowance, the Finnish ideal of promoting the livelihoods of the most vulnerable is changing. While adult education is a key institution to provide equal chances to all social groups at the labour market, the access to these opportunities may become limited to insider groups. The finding that mothers, particularly non-married or with small children, are most disadvantaged in the UK adult education system, presents an alarming example to be avoid in the Finnish context. Therefore, in order for the Finnish economy to maintain a sustainable labour force, the opportunities to adapt to the changing work and family situations should be guaranteed to everyone despite their available resources.

This blog post is based on the research article: Pöyliö, H. & McMullin, P. (2024), Participation in formal adult education and family life—a gendered story, European Sociological Review, jcae032,

Interested to read more? A policy insight about the findings.

More information by email: Heta Pöyliö heta.poylio@utu.fi

The authors are Researcher Heta Pöyliö and Academy Research Fellow Patricia McMullin at INVEST Research Flagship Centre.

References

European Commission (2023) European Skills Agenda – Factsheet. [retrieved 19 November 2024]

Eurostat (2020). Participation rate in education and training by sex (trng_aes_101). [retrieved 5 August 2024]

McMullin, P., & Kilpi-Jakonen, E. (2014). Cumulative (Dis)advantage? Patterns of participation and outcomes of adult learning in Great Britain. In Blossfeld, H-P., Kilpi-Jakonen, E., Vono de Vilhena, D. & Buchholz, S. (Eds.), Adult Learning in Modern Societies: An International Comparison from a Life-Course Perspective. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp 119–139.

Stenberg, A. (2010) The impact on annual earnings of adult upper secondary education in Sweden. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 29(3), 303-321.

Stoilova, R., Boeren, E. and Ilieva-Trichkova, P. (2023). Gender Gaps in Participation in Adult Education in Europe: Examining Factors and Barriers. In Holford, J., Boyadjieva, P., Clancy, S., Hefler, G. and Studená, I. (Eds.), Lifelong Learning, Young Adults and the Challenges of Disadvantage in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 143-167.

Triventi M. & Barone C. (2014). Returns to Adult Learning in Comparative Perspective. In H.-P. Blossfeld, H.-P., Kilpi-Jakonen, E., Vono de Vilhena, E. & Buchholz, S. (Eds.), Adult Learning in Modern Societies. An International Comparison from a Life- Course Perspective. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, pp. 57-75.

Työllisyysrahasto (2024) Perustietoa aikuiskoulutustuesta. [retrieved 19 November 2024]

Vono de Vilhena, D., Kosyakova, Y., Kilpi-Jakonen, E., & McMullin, P. (2016). Does adult education contribute to securing non-precarious employment? A cross-national comparison. Work, Employment and Society, 30(1), 97–117.

Leave a Reply