Sanni Kotimäki, Simon Chapman & Satu Helske

INVEST Blog 14/2021

The upcoming Finnish parental leave reform – to be launched in 2022 – aims at providing families more opportunity, flexibility, and freedom of choice than the current system in their family leave decisions. Family leaves are political, as their short- and long-run influences can extend both to the socioeconomic position of men and women, and to children, families, and the whole society. The forthcoming family model also seeks to allocate family leaves and care responsibilities more equally between the parents and thus strengthen equality in working life and reduce the gender wage gap. The reform will entitle both mothers and fathers to an equal quota of family leave.

It is crucial to understand the effects of family leave reforms and take-up of parental leave on families, and the factors that explain these effects. However, policy impact evaluations are still rare, even though policy evaluation is societally important in many ways. In welfare states, policy reforms are often expensive, and due to restricted resources, inefficient systems should not be maintained, which is also one of the main starting points in INVEST research.

Exploring complex social phenomena and effects is, unsurprisingly, complex and difficult. Due to the background selection in the use of paternal leave, effects are harder to locate using observational, non-experimental research designs, such as surveys. Surveys typically use limited and at least slightly skewed samples (for example, mainly highly educated men who have taken longer parental leave).

In the PREDLIFE project, which is part of INVEST and started at the beginning of the year, we use full population registers to analyse how interventions and reforms (especially parental leave reforms) shape individual and family life-courses. Life-courses consist of separate but parallel and interrelated trajectories (pathways), such as changes in family structure and employment, career, and income developments for women and men. Information on the impact of legal reforms on people’s lives can be used to assess the effectiveness of social reforms. In addition, it is scientifically important to better understand the dynamics of family and career transitions, which in turn helps to better predict the effects of future legal reforms.

Fathers’ use of family leave

The effects of parental leaves have previously been studied (to some extent) using so-called quasi-experimental research setups, comparing the families of children born right before the reform with those born just after the reform. Based on this research, most family leave reforms have had an impact on the use of paternity leave, but not all (Lassen 2020). This has been most studied in Sweden, where the increase in the father’s quota, referring to leave only for the father, has been found to clearly increase the use of leave, but the so-called equality bonus aimed at even distribution of leave between the parents had no effect on the leave use (e.g., Duvander & Johansson 2012).

In Finland, the reforms have also increased the utilization of the father’s quota, although in the most recent 2013 reform this seems to have been mainly due to the extension of leave periods and not so much to the fact that more fathers have started utilizing the quota (Saarikallio-Torp & Miettinen 2021).

The majority of fathers make at least some use of family leave, but the proportion of fathers who do not take it at all has remained at around 25 % despite the reforms. Fathers mainly use earmarked leave: about 70 % of all fathers have taken the three weeks’ birth-related paternity leave and about 50 % ‘independent’ paternity leave, while the sharing of parental leave is relatively rare.

In all families, the use of paternity leave does not mean that the father is primarily independently responsible for caring for the child: in 64 % of families who took advantage of the father’s month available in 2011, the mother had also been at home at least part of the father’s month (for example, on annual leave or as unemployed), and only one-third of fathers reported in the survey that they were largely independently responsible for caring for the child during their leave; it was more common to share care responsibilities with the mother (Salmi & Närvi 2017). Unfortunately, there is no research of this type regarding the longer paternity leaves available since 2013.

In Finland, paternity leave is more often used by fathers with higher education and higher income, while in lower socioeconomic groups it is more likely not to take paternity leave at all or to use only the period with the mother immediately after birth (Miettinen & Saarikallio-Torp 2020; Saarikallio-Torp & Miettinen 2021). According to survey studies, the main motivating factors for taking or not taking paternity leave have been related to the father’s work or the mother’s education or return to work, the family’s income level, and the father’s desire to care for the child (Eerola et al. 2019).

Fathers primarily use the ear-marked leaves for fathers, while the non-allocated part is mainly used by the mothers. A study comparing Finnish- and Swedish-born fathers living in Finland and Sweden concluded that differences in fathers’ family leave use between Finland and Sweden were more significantly related to the differences in legislation than in culture, but cultural factors also explained the differences to some extent (Mussino et al. 2019).

However, cultural norms change over time: nowadays, fathers’ use of parental leaves keeps increasing and fathers also spend more time with their children. The time working fathers spend caring for children has also increased significantly in recent decades. For fathers of young children, the increase from 1988 to 2010 was as high as 60 per cent, so that fathers already accounted for 41 % of the total time parents spent on childcare (Miettinen & Rotkirch 2012). It is assumed that the share has further increased in the 2010s, of which the 2020 time-use survey will provide more information.

The various effects and mechanisms of fathers’ family leaves

Because fathers who take leave and fathers who do not use it differ in terms of background factors, such as education and the labor market status, it is not possible to view the consequences of using paternity leave directly by comparing the fathers who have taken different amounts of paternity leave. Examining the legal reforms that have increased the use of paternity leave provides more reliable information not only on the use of leave, but also on the consequences of using leaves.

In other countries, the past reforms that have increased the use of fathers’ leaves have had various effects on the lives of family members. In the Nordic countries, the reforms have e.g. improved the mothers’ employment, increased the probability of having the next child, reduced the risk of parental divorce, and improved children’s school performance (Cools et al. 2015, Dunatchik & Özcan 2021, Duvander et al. 2019, Lappegård et al. 2020). On average, fathers who took paternity leave have had closer contact with their children even after a possible divorce (Duvander & Jans 2009).

The long-term effects of paternity leaves are likely to be mainly indirect and are explained, for example, by a more even division of labour between parents, as observed in Sweden (Evertsson et al. 2018). On the other hand, the research evidence in this respect is still somewhat contradictory (Ekberg et al. 2013; Hosking et al. 2010).

Does the workplace play a role in fathers’ use of leave?

Most research on taking family leave has so far focused on either the background factors of the father or family or, on the other hand, on country comparisons and the examination of differences in legislation. However, country-level cultural factors constitute just one social environment that may affect the use of paternity leave, although in practice fathers can live and work in very different types of environments within countries. In our current work, we approach the issue from the perspective of different social contexts, of which we wanted to study particularly the importance of workplaces.

Based on previous research, paternity leave in Finland is more often held in the public sector, large employers, female-dominated professions, in education, social work, and health care positions, and in workplaces where colleagues are higher educated (Saarikallio-Torp & Haataja 2016). Similarly, in a Swedish study, first-time fathers who worked in larger jobs and in the public sector were more likely to use paternal leave (Bygren & Duvander 2006). The share of leave-takers was also higher in female-dominated fields, but this seemed to be rather related to the role of the public sector. Fathers took parental leave slightly more often in jobs where a larger proportion of other fathers had taken a leave. In another Swedish study, uncertainty or flexibility in working life explained little of the variation between fathers, and the use of paternity leave was best predicted by occupational status, with those in a higher position taking more leave (Eriksson 2018).

In our research article, we examine the role of the industry and workplaces in using paternity leave, especially from the perspective of the role of sex ratio in the industry and the workplace. We will further study how spousal income differences and the childcare arrangements made earlier by other family members and close relatives are related to taking paternity leave. We focus on fathers of children born between 2007 and 2018, to whom we have linked information about their social environments (family, relatives, and workplace).

Our article is still unfinished, but in honor of Father’s Day, here are some statistics on the use of family leave by working fathers. Unfortunately, the Finnish register data we have in use do not currently contain direct information on the duration of paternity leave, so we infer this from income and the daily parental allowance paid to the father.

Legislation on paternity leave has changed numerous times in the 21st century (Eriksson 2018, Kellokumpu 2007, Miettinen and Saarikallio-Torp 2020). Fathers of children born in 2007 had to take paternity leave within six months after the end of parental leave, while in the case of children born in 2016, paternity leave was available until the child’s two-year birthday.

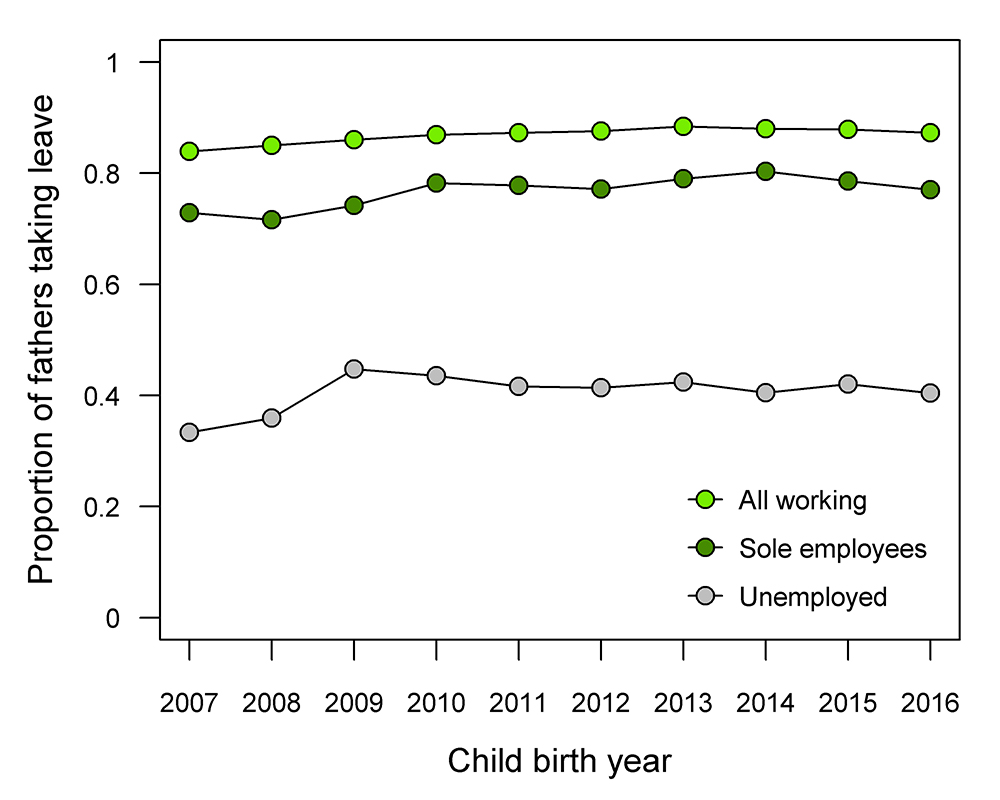

Figure 1 shows the share of fathers who took paternity and / or parental leave (hereafter referred to as family leave) of all fathers entitled to these leaves in the different labor market situation groups (in the year the child was born). Overall, about 84 % of the employed fathers who had a child in 2007 and 87 % of fathers of children born in 2016 were on family leave. The share of fathers who took family leave was clearly higher in the employed than in all fathers (about 75 %).

The proportion of leave-takers was clearly smaller in self-employed than employed fathers: 73 % of fathers of children born in 2007 and 77 % of fathers of children born in 2016. However, the clear majority of the self-employed took advantage of family leave. Among unemployed fathers, on the other hand, taking (official) family leave was clearly less common: 33 % of the unemployed fathers who had a child in 2007 and 40 % of the unemployed fathers who had a child in 2016. The proportion of unemployed fathers taking parental leave was the highest in 2009 during the financial crisis.

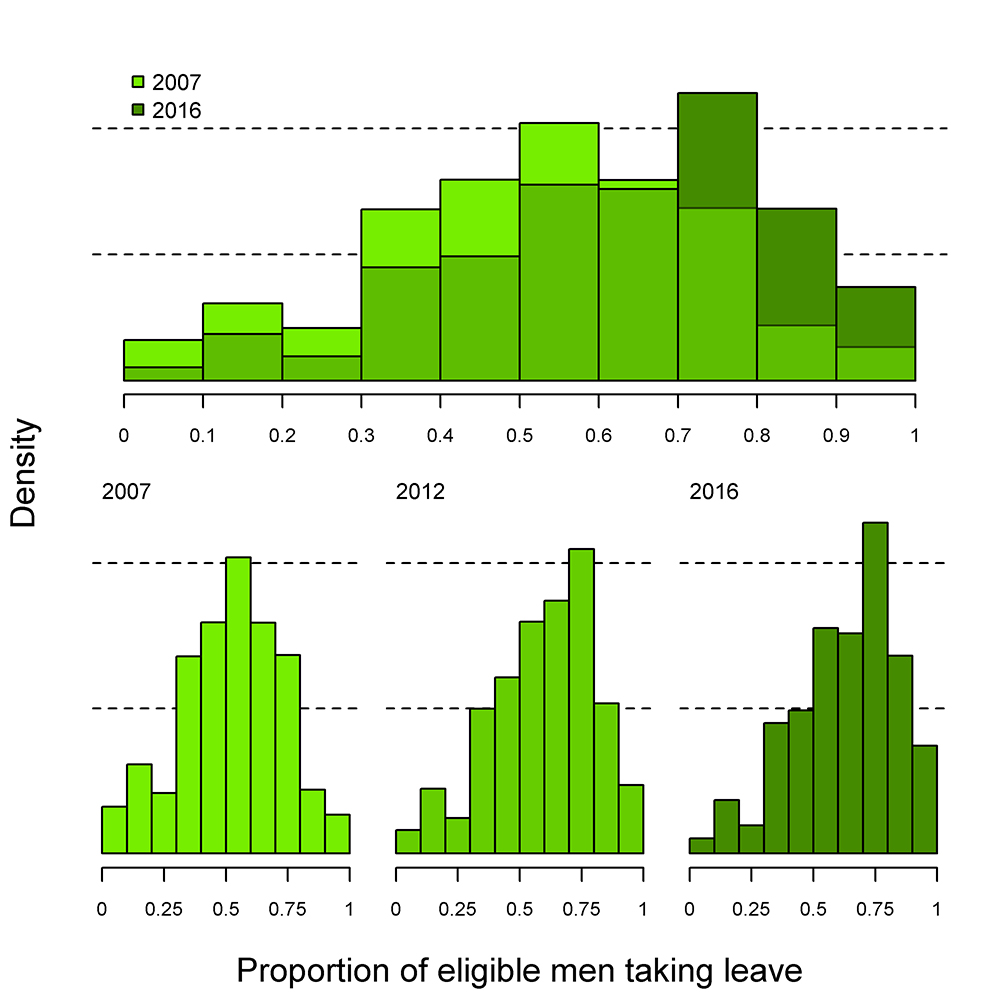

Figure 2 shows the proportion of men who took family leave, i.e., paternity or parental leave, of men who were entitled to leave during each year. Only workplaces with at least five fathers entitled to leave were included. Most workplaces in Finland are small and do not include any fathers entitled to family leave (79 % of workplaces in 2007 and 85 % in 2016). 92 % of workplaces even having fathers entitled to leave had less than five such fathers, and it is not sensible to compare the proportions for such small numbers. The figure thus tells mainly about the situation at medium-sized and large workplaces: the median number of employees, i.e. the middle number of employees in the workplaces organised by size, was 120 in 2007 and 102 in 2016, while the average of all workplaces was only about three employees. Although the share of companies included in the analyses is small, about half of all fathers entitled to paternity leave work in these places.

The upper part of Figure 2 compares the proportions of fathers who took leave in 2007 (light green distribution) and 2016 (dark green distribution) in workplaces with at least five fathers entitled to leave. The lower part of the figure shows the proportion of men who took leave separately for 2007, 2012, and 2016. In the figure, number 1 means that all men entitled to leave also took some leave, and number 0 means that no one took it. Already in 2007, in only a small proportion of workplaces fathers did not take any leave at all. However, the proportion of men taking leave clearly increased by 2016, when the vast majority of fathers took family leave in most workplaces. In 2007, the median of leave-takers in these workplaces was 57 per cent, and 67 per cent in 2016. In all workplaces, the corresponding proportions were somewhat lower, at 51 % and 60 %, but the growth was similar.

Two percent of those entitled to paternity leave were self-employed in 2007 and five percent in 2016. Among them, the annual proportions of those who took paternity leave were clearly lower: 38 % in 2007 and 45 % in 2016. When interpreting the figures, it is worth noting that the annual proportions are thus lower than the proportions of fathers who took paternity leave at all.

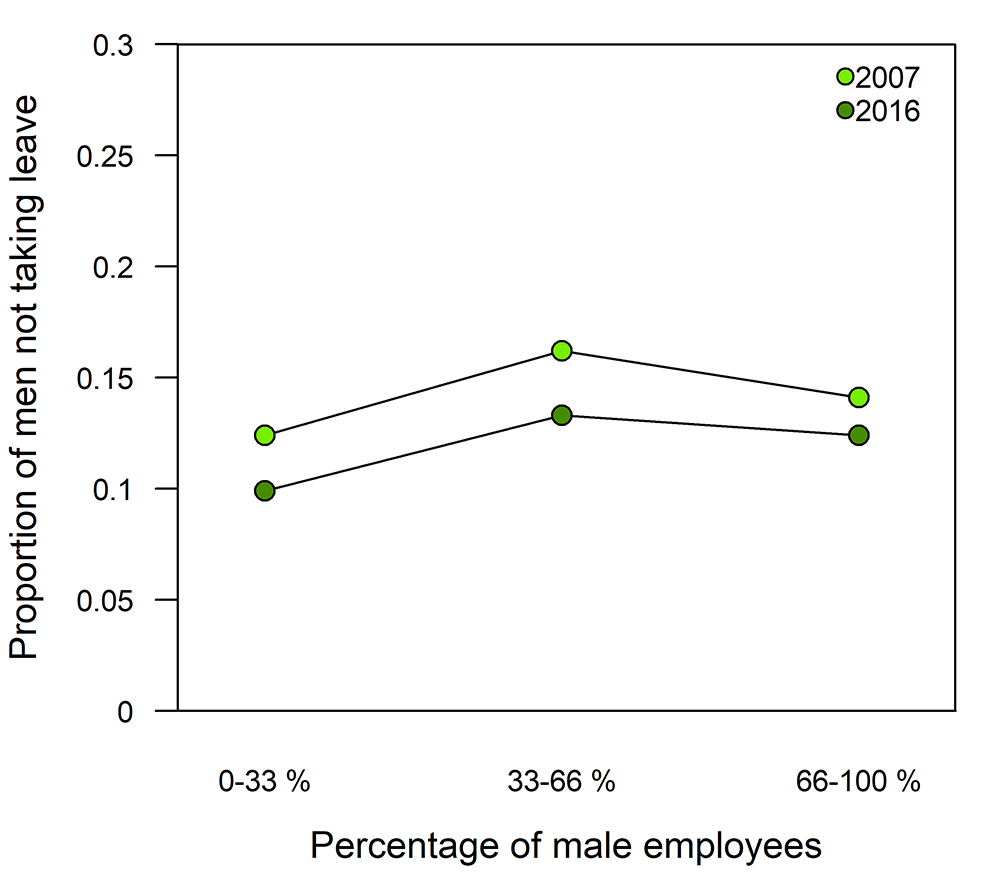

There are some differences in the fathers’ use of leave by how male or female-dominated their workplaces are. Figure 3 shows the proportion of fathers who did not take any leave in relation to the proportion of men in the workplace. Men working in female-dominated workplaces (less than 33 % of male employees) took slightly more leave than other fathers; only 12 % had not taken family leave in 2007 and 10 % in 2016. In the male-dominated and more (sex ratio) balanced workplaces these shares were 2 to 4 percentage points higher.

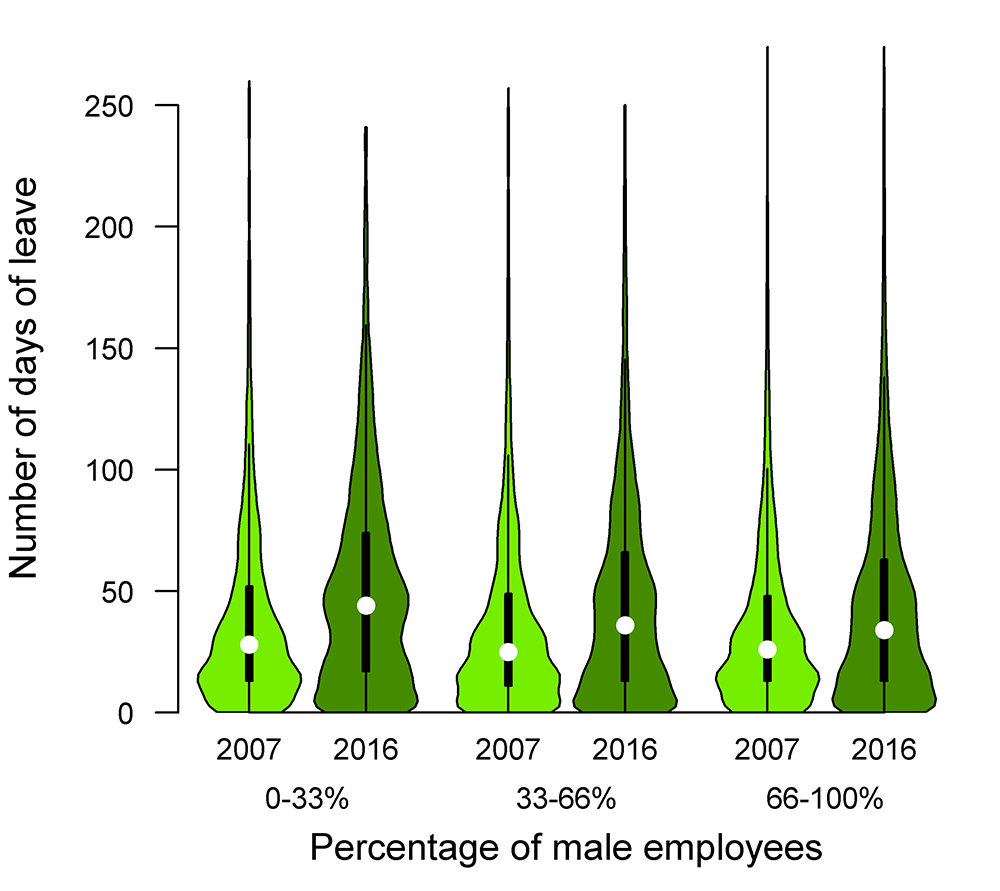

Figure 4 shows the median duration of family leave (white), the average 50 % (black) and the smoothed distribution of durations in 2007 and 2016 in relation to the share of men in the workplace. The width of the coloured pattern roughly refers to the proportion of those who took a leave of a certain length: the wider, the more leave of that length. The distributions are broad at the base, so most men considered relatively short vacations. The figures show the elevations at the 18-day (three-week) paternity leave with the mother and at the ear-marked paternity leave, i.e., the so-called independent leave (24 working days in 2007 and 54 working days in 2016).

On average, the longest leaves in both years were taken by fathers who worked in clearly female-dominated workplaces, most typically in health and social services, education, and commerce. In this group, the increase over time was also the largest, averaging about 28 days to 44 days. At clearly male-dominated workplaces (typically in manufacturing, construction, and trade), the growth ranged from around 26 days to 34 days and at workplaces with roughly even sex ratio (typically in manufacturing, commerce, and science and technology) from around 25 days to 36 days.

It is clear that female-dominated industries have a long history of arranging family leave, which may also lower the threshold for taking paternity leave. On the other hand, based on these simple statistics, we are not able to say to what extent a workplace or industry may influence the use of paternity leave or whether it is a result of different types of fathers ending up to (“self-selecting” into) certain types of industries and workplaces.

Next steps

The main objective of PREDLIFE project is to better understand the life-course effects of (men’s) parental leave take-up as well as develop an analytical model for statistical modelling, predicting, and visualising the effects of political reforms and interventions. This objective is approached with a multidisciplinary team, as the project consists of the sociological substudy conducted at the university of Turku and the statistics substudy conducted at the University of Jyväskylä. The methodology to be developed will become open access and thus it will also be available for the broader research community.

Authors

Sanni Kotimäki works as a senior researcher in INVEST sociology and PREDLIFE. Her previous research covers intergenerational processes, life-courses, and health disparities, focusing on the role of early-life exposures and socioeconomic resources. Her thesis will be publicly examined soon.

Simon Chapman works as a senior researcher in INVEST sociology and PREDLIFE and holds a PhD in evolutionary biology. His previous research focused on the role of grandmothers in the evolution of post-reproductive lifespan, and on life-histories in both humans and Asian elephants.

Satu Helske is a senior researcher in INVEST sociology and FLUX consortium, the leader of the PREDLIFE consortium, and holds a PhD in statistics. Her research focuses on inequalities and intergenerational effects, dynamics of work and family across the life-course, and the parental leave use and its consequences in parents’ life-course.

Literature

Bygren, M., & Duvander, A.-Z. (2006). Parents’ workplace situation and fathers’ parental leave use. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(2), 363–372.

Cools, S., Fiva, J. H., & Kirkebøen, L. J. (2015). Causal effects of paternity leave on children and parents. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 117(3), 801–828. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12113.

Dunatchik, A., & Özcan, B. (2021). Reducing mommy penalties with daddy quotas. Journal of European Social Policy, 31(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928720963324

Duvander, A.-Z., & Jans, A.-C. (2009). Consequences of Father’s Parental Leave Use: Evidence from Sweden. Finnish Yearbook of Population Research, 44, 49–62. https://doi.org/10.23979/fypr.45044

Duvander, A.-Z., & Johansson, M. (2012). What are the effects of reforms promoting fathers’ parental leave use? Journal of European Social Policy, 22(3), 319–330.

Duvander, A.-Z., Lappegård, T., Andersen, S. N., Garðarsdóttir, Ó., Neyer, G., & Viklund, I. (2019). Parental leave policies and continued childbearing in Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. Demographic Research, 40, 1501–1528.

Eerola, P., Lammi-Taskula, J., O’Brien, M., Hietamäki, J., & Räikkönen, E. (2019). Fathers’ leave take-up in Finland: Motivations and barriers in a complex Nordic leave scheme. SAGE Open, 9(4), 2158244019885389.

Ekberg, J., Eriksson, R., & Friebel, G. (2013). Parental Leave – A Policy Evaluation of the Swedish “Daddy-Month” Reform. Journal of Public Economics, 97(1), 131–143.

Eriksson, H. (2018). Fathers and Mothers Taking Leave from Paid Work to Care for a Child: Economic Considerations and Occupational Conditions of Work. In Stockholm Research Reports in Demography: Vol. 2018:12.

Evertsson, M., Boye, K., & Erman, J. (2018). Fathers on Call? A Study on the Sharing of Care Work between Parents in Sweden. Demographic Research, 39(1), 33–60.

Hosking, A., Whitehouse, G., & Baxter, J. (2010). Duration of leave and resident fathers’ involvement in infant care in Australia. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1301–1316.

Kellokumpu, J. (2007). Perhevapaiden kehitys 1990–2005: Isillä päärooli uudistuksissa, sivurooli käyttäjinä. Helsinki: Palkansaajien tutkimuslaitoksen raportteja, 10.

Lappegård, T., Duvander, A.-Z., Neyer, G., Viklund, I., Andersen, S. N., & Garðarsdóttir, Ó. (2020). Fathers’ use of parental leave and union dissolution. European Journal of Population, 36(1), 1–25.

Lassen, A. S., & others. (2020). Gender Norms and Specialization in Household Production: Evidence from a Danish Parental Leave Reform. Copenhagen Business School [wp]. Working Paper / Department of Economics. Copenhagen Business School No. 04-2021.

Miettinen, A. & Rotkirch, A. (2012). Yhteistä aikaa etsimässä. Lapsiperheiden ajankäyttö 2000-luvulla. Perhebarometri 2011. Väestöntutkimuslaitos – Katsauksia E 42/2012. https://www.vaestoliitto.fi/uploads/2020/12/34c6d1e0-perhebarometri-2011.pdf

Miettinen, A., & Saarikallio-Torp, M. (2020). Trends and socioeconomic differences in the use of father’s parental leave quota [Isälle kiintiöidyn vanhempainvapaan käyttö ja sen taustatekijät]. English summary in the end. Yhteiskuntapolitiikka, 85(4), 345–357. https://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/140463/YP2004_Miettinen&Saarikallio-Torp.pdf?sequenc8e=2

Mussino, E., Tervola, J., & Duvander, A.-Z. (2019). Decomposing the determinants of fathers’ parental leave use: Evidence from migration between Finland and Sweden. Journal of European Social Policy, 29(2), 197–212.

Saarikallio-Torp, M., & Miettinen, A. (2021). Family leaves for fathers: Non-users as a test for parental leave reforms. Journal of European Social Policy, 31(2), 161–174.

Salmi, M., & Närvi, J. (2017). Perhevapaat, talouskriisi ja sukupuolten tasa-arvo. Helsinki: Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitoksen raportti 4/2017. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-302-884-5

Information on parental leave reform: https://www.kela.fi/web/en/family-leave-reform-2022