In this post, I discuss the similarities and differences between historiography and futures studies on the basis of David J. Staley’s book History and Future. I also sketch a structural-taxonomical approach to the possible futures.

It is one thing to say that our knowledge of the past is necessary for our knowledge of future, but another to say that the way we think about the past is useful in thinking about the future. In order to establish the latter claim, we need to tell how the past is made understandable and how this relates to future-oriented thinking. I will not hide my answer: In my view, we understand history by tracking down patterns of counterfactual dependencies. There is no in-principle difference between studying counterfactual histories and possible futures. In both cases, we need to go beyond direct evidence and the actual historical trajectory. However, this is only the backbone of the similarities between historiography and scenario-work. Many details must be filled in.

A useful book to approach the issue of historiographical thinking in scenario work is David J. Staley’s History and Future. In the book, Staley argues that historiographical (or “historical” as he calls it) thinking is useful in thinking about the future. In my view, the general outline of Staley’s argument is correct, but many important topics are not discussed in enough detail. In this post, I discuss those shortcomings and argue that the details are essential in order to understand the similarities and differences between historiography and scenario-work.

Evidence

Staley argues that historiography begins from the need to answer some question (p. 48). In order to answer a question, a historian uses evidence, i.e. “something that make something else evident” (p. 49). In a similar manner, scenarists (i.e. people who produce scenarios for the future) ask questions and seek for evidence. “Evidence of the future lies all around” (p. 58).

Surely both historiography and scenario-work must be based on evidence. The problem is that Staley does not tell how, exactly, we can know that a piece of evidence can answer our question. Staley cites Michael Stanford (p. 49): “Virtually anything in the world may be evidence for something else if a rational mind judges it so”. This is not helpful and adds a layer of mysticism on historiography (and scenario-work). Moreover, the answer hides important differences between historiography and scenario-work.

In general, we can say that some present object is evidence for some past event if there exists a causal connection between the two. A diary telling that soldiers came under heavy bombardment is evidence of the heavy bombardment if and only if the heavy bombardment caused a person to write the entry. Our ability to judge some object as a piece of evidence depends on our ability to track down a causal process from the object to the event.

This causal scheme cannot be applied straightforwardly in scenario work. If we were able to know that some object is evidence for some future state of the world, we would already know the causal processes of the future. In order to know those processes, we need evidence. There is a circle here. Is it vicious?

Not necessarily. In the case of historiography, we need to establish the relationship between many pieces of evidence in order to establish the nature of each individual piece. Staley points out (p. 61-62) that evidence needs to be understood in the context of other pieces of evidence. In order to understand what some piece of evidence tells us about the past/future, we need to consider other evidence of the past/future. If historiography is to be trusted, the circle cannot be vicious.

However, there are still important differences between historiographical evidence and evidence in scenario-work.

First, in historiography, some sources describe what happened and provide us with fixed points around which we can build our picture of the past. Unless we fall into universal skepticism, there is no reason to doubt that at least some of these are trustworthy. There are no similar descriptions of future events. This makes it much harder to place evidence in the context of other evidence.

Secondly, a historical event is a common cause of many pieces of evidence while our evidence of the future stands in a much more complicated relationship with the future.

Thirdly, isolated historical events or processes (i.e. events that are surprising findings of historiography that are not connected to known events and processes) are an exception and most of the history and historical knowledge is continuous. What I mean by this is that we are in connection with the past due to the flow of information about the past to present. For example, ever since the WW2 there has been knowledge and discussion about the event. The present-day historians do not have “make up” the event from scratch but can rely on previous knowledge. (This knowledge might be misleading but still exists as a point of departure.) We are not in a similar connection with the future. Of course, we can base our future estimations on previous future estimations by improving them on the basis of new insights, but those previous estimations are no closer, causally speaking, to the future than the later ones. In fact, they are farther away.

Finally, the fact that historiography and scenario-work both use evidence does not imply that there is a special connection between the two, as an inquiry on any subject is based on evidence. We would like to hear why historiographical thinking about evidence is especially useful in scenario-work. This leads us to the next topic, contextual thinking.

Contextual thinking

Staley discusses “contextual thinking” in many different parts of the book without distinguishing two different meanings of “contextual thinking” seems to have in his thinking: 1. An inferential meaning, and 2. An ontological meaning. In the first sense, contextual thinking is a way to bridge the gap between evidence and reality. In the second sense, contextual thinking is a way to understand causal relationships.

1. Staley argues that “Thinking about the future, like thinking about the past, requires contextual thinking. [–] the historian of the future draws high-context, ampliative, nondemonstrative inferences from the evidence” (p. 62). A historical statement, i.e. “a formal sentence that contains the inference from the evidence” (p. 54), is produced by studying many pieces of evidence in connection with each other and by making inferences from the set of evidence as a whole. What are the properties of adequate contextual thinking? Unfortunately, Staley does not answer this question. He merely states that “The judgement, skill, and wisdom of the historian play an important role in the creation of statements about the past” (p. 55). We wanted to know how historiographical thinking can be used in scenario-work. That skill and wisdom are useful does not clarify the philosophical underpinnings of scenario-work. Moreover, Staley argues that we can tell which historical statement is a truthful one. How? By consulting which of the statements is determined by experts to be closer to the truth (p. 55). This does not tell us anything about the use of historiographical thinking in scenario-work. Surely, we need to have debate and expert judgement, but the important question is how these debates work and do their logic make the outcome adequate. In order to answer the question, we need to take a look at the philosophical theories of historiographical inferences, something that cannot be done in the limits of this post.

I do not want to sound too critical. I do think that placing evidence in the context of other evidence is useful. Given that the goal of scenario-work is not prediction but formulation of possible futures, it is probably useful to analyze any given piece of possible evidence in connection with other sets of evidence. In this way, it is possible to understand that the same piece of information might indicate many different futures. The lack of detailed analysis of contextual thinking in Staley’s book is disappointing for the very reason that contextual thinking (of evidence) could be highly reasonable.

It is also possible that contextual thinking is itself contextual, i.e. there might not be any general guidelines how to proceed in such thinking, but the adequacy of a thought process must be decided case-by-case. I am somewhat inclined to this opinion, given that I view historiography as a heterogenous field where many different types of considerations can play a role. However, if it is the case that nothing general can be said about the general structure of historiographical thinking (contextual thinking probably being a part of the structure) then nothing general can be said about the use of historiographical thinking in scenario-work. The usefulness has to be decided case-by-case (and the question, of course, is “How?”). I do not believe in this. I think there are patterns in historiographical thinking that make it useful with respect to scenario-work. I clarify the issue below.

2. Staley argues that “Human behavior and actions do not conform to law-like patterns and rhythms because they are also influenced by the unique situations within which these behaviors and actions are embedded” (p. 82, emphasis added).

The claim that historiography studies unique situations and their effect on the development of history has often been made. This claim can be understood in three ways (at least).

1. Historiography studies conceptually unique situations. We cannot use the same concepts or categories to describe different historical situations. For example, the concept “doing science” cannot be applied to both Aristoteles and Newton without distorting their activities. Staley rejects this view (95-96) and so do I (see Virmajoki 2019, ch. 7).

2. Historiography studies unique causal configurations. A historical development is a consequence of a causal configuration that is unlikely to occur again. The same types of causes may occur in many contexts, but their combination is unique.

3. In a historiographical explanation, details are a virtue. Historiography is characterized by its attempts to provide details while other disciplines attempt to avoid complexity in the form of details (Staley accepts this; p. 82-83).

The most natural way to interpret the ontological sense of “contextual thinking” is a combination of 2 and 3. Historiography indeed often seems to be able to give more detailed pictures of the development of human activities than more theoretical disciplines. For example, historiographical analyses of science differ from philosophical analyses. While philosophers of science are interested in general patterns and activity-types in science, historians focus more often on more specific questions. However, it is not obvious which one of these approaches is more fruitful. Usually, scholars (at least in philosophy) think that general considerations and details should be balanced. The difficult question is how that balance can be achieved.

I think the same is true in historiography in general. It is not obvious why details and unique contexts should be so important. One could argue that history just happens to be complex and non-repeating. However, if this is the answer, the value of contextual thinking in scenario-work becomes unclear. Let me explain.

Contextual thinking could be useful in deciding the current causal configuration (of the state of the world under interest) and analyzing the possible effect of that configuration, i.e. the most probable future state. Staley seems to suggest this “[T]he flow of events depends on the particular context of the situation, which may be unique to a certain time and place. Evidence must be understood within the context of other pieces of evidence” (p. 61). It seems that inferential and ontological contextual thinking come together. By analyzing a set of evidence as a whole, we come to understand the current causal configuration. Once we understand the causal configuration, we are able to infer its effect, i.e. the future state of the world. So far so good, contextual thinking seems like a promising way to approach the future.

However, the issue becomes more complicated once we notice that the point of scenario-work is not to tell what probably will happen but to describe many possible futures. “Rather than imagining a sequence of event, the scenarists attempts to manage the uncertainties of the future by discerning three or four possible contexts” (p. 84). Notice that here the inference is not

evidence -> current causal configuration -> future effect,

rather it is:

(subset of) evidence -> possible future causal configuration -> possible events in the configuration

In the latter inference, ontological and inferential contextual thinking do not coincide when we take the first and crucial step (first arrow).

Given that evidence of the future is much more difficult to gain than evidence of the past and given the effort required to describe even past contexts in detail, it is difficult to understand how it could be possible to formulate plausible future contexts. Surely, it seems that if we are able to understand past contexts, it becomes possible to formulate future contexts. However, the problem is not in the machinery but in the epistemology. Given that there can be countless configurations, how can we separate plausible future configurations from far-fetched ones? The problem of evidence of the future (see above) is not resolved by contextual thinking. Rather, the problem makes the epistemic underpinnings of contextual thinking in scenario-work a mystery.

Staley argues that scenario-work should focus on the structures of the future, not events (ch. 3). This might seem to solve the problem above. If we are not interested in particular events, then it might be possible to limit the amount of information we need to provide about the details of a causal configuration. However, in this case contextual historiographical thinking would become redundant. What was supposed to be a strength of historiography, contextual thinking and focus on details, would only harm our attempts to get rid of details.

While I think that the focus on the structures of the future is the best insight of the book, it also seems that contextual and detail-oriented thinking cannot help in this respect due to the problems introduced above. How should we think of the structures?

Structures of the Future

I suggest that theoretical knowledge is in the essence of understanding the possible structures of future within which more specific events take place. It is a nice coincidence that Kuhn named his famous book “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions” as this sense of structure is what I have mind in here. Let’s use Kuhn as an example as he is well known (I am not suggesting that he was right).

In the philosophy of science, there are many theoretical accounts of how science develops (focusing either on the whole or to some more specific question like theoretical continuity in science). One of them is Kuhn’s theory of paradigms, where science is dominated by a paradigm which defines the theoretical, methodological, conceptual, axiological and conceptual resources that the science has as well as the kinds of problems it attempts to solve. No paradigm lasts forever. Rather, each paradigm faces problems, anomalies, that it cannot solve, and once these become severe enough, a change in paradigm becomes possible. This change is a scientific revolution, and how that revolution will end is not determined by straightforward dynamics.

We could think that Kuhn’s theory defines a possible structure of future of science. If Kuhn is right, whatever the details, science will be dominated by a paradigm or there will be a revolution. In some cases, we might be able to determine the contest of a structure, i.e. to tell what that paradigm will be (in the case of revolution this is much more difficult if not impossible). For example, if a new particle accelerator is built, we might guess that it will shape the paradigm. Finally, some there will be some events within the structure and its contents, but we are not interested in these per se. Individual events are too difficult to predict but we could – like Staley suggests – tell what kind of events are possible within a structure and its contents. For example, we can estimate that if the new accelerator is built, certain types of experiments will happen.

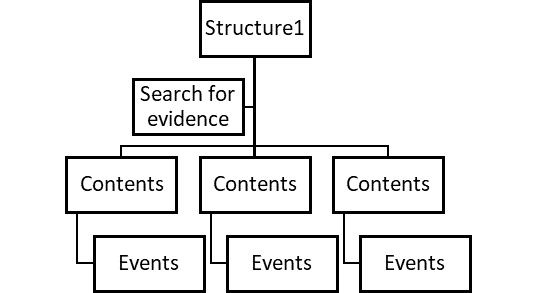

Moreover, we can understand the search for evidence within this structural scheme. A structure, not evidence, is the starting point. Once we have decided what kind of structure our theoretical understanding allows, we can look for evidence for the contents of that structure. So we have the following scheme:

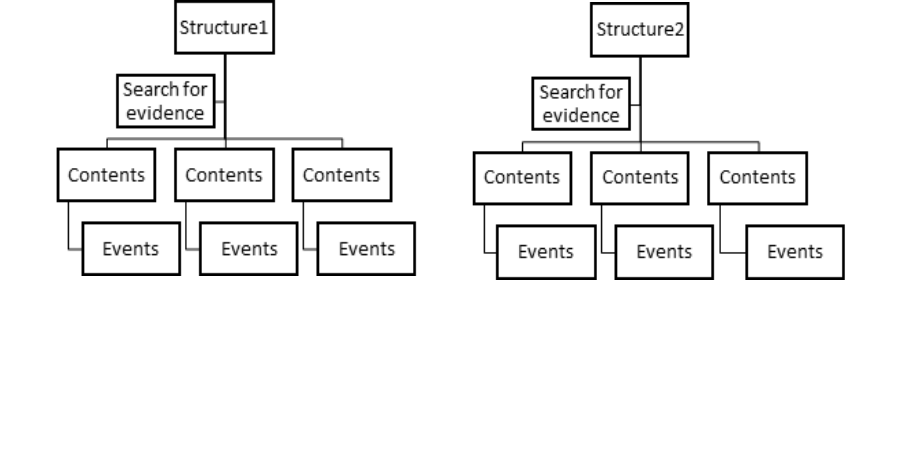

Moreover, there does not exist a single possible structure. Rather, we have many theories of science that define their own structures. For example, structural realism often commits to the view that the mathematical structures of successful theories are preserved during scientific change. This view implies that no dramatical changes á la Kuhn will happen. Given the different structures, we can formulate taxonomies of possible futures:

Such taxonomies are useful because (I) their theoretical bases are transparent, (II) they allow us to see at a glance what kind of futures are possible, and (III) they show whether some scenario is possible within many structures.

I cannot go to details of the epistemology of such taxonomies in this post. However, we can note that the credibility of an individual structure depends on the credibility of its theoretical basis. While these bases are difficult evaluate (in the philosophy of science, this is known as the problems of testing philosophical theories), considerations of historical relevance, coherence, simplicity, and explanatory power are relevant. It is also better to rely on transparent theoretical basis than to some mystical “contextual insights” or what have you.

We could also add some normative considerations. We might ask which of the potential theoretical basis shows science in a favorable light. We could then formulate a future structure by using that basis. These structures would describe desirable futures.

Moreover, we can evaluate the usefulness of individual structures in scenario-work on the basis of (i) how easy it is to collect evidence for individual contents within the structure, (ii) the number of possible contents (too many are difficult to manage), and (iii) the consequences of different contents on our ability to act (too pessimistic or optimistic are to be avoided). While these practical criteria may leave outside real future possibilities, they still enable us to direct our limited resources to understanding futures that we might achieve (or avoid).

Finally, it must be pointed out that these taxonomies tie together historiography and future. First, the philosophical theories of science are often based on historical considerations. Understanding history is necessary to create and evaluate possible structures. Secondly, both (i) historical understanding and (ii) scenario-work are based on understanding what could have been the case and structural considerations are necessary in achieving this understanding.

Counterfactuals

After pointing out that our evidence of the future is more difficult to find than evidence of the past, Staley takes a step to the right direction. “If we are to think seriously about the future, we must ‘fill in’ the missing information to the best of our ability. [–] To resolve this issue, it might be instructive to consider the parallels between histories of the future and counterfactual histories. [–] In both cases, the historian must make an inference about events and situations that have not occurred.” (p. 63). Now the idea is that if we are able to think rigorously about historical counterfactuals, we are also able to think rigorously about the future. I agree. However, the short answer for what makes a counterfactual scenario plausible that Staley gives, i.e. “We should consider as plausible or probable only those alternatives which we can show on the basis of contemporary evidence that contemporaries actually considered” does not work, as I have explained in detail elsewhere (see this post). We have to do better, and the structural approach above helps us.

Historical counterfactual provides us with information of the form “Alternative Y rather than actual X would have happened, had W rather than (actual) Z happened”. For example, we can say that “Scientists would not have believed in atoms, had Einstein not explained the Brownian motion”. In order to establish such claim, we need to

1. Consider evidence of the actual world. We need to find “causal clues” of the possible process from Z to X. For example, we could find a diary or letter where a scientist describes how Einstein’s work impacted her believes. Such evidence is not always found and is never conclusive. For example, I could write in a diary that I voted in an election because one of the candidates was so impressive. However, I might have voted in any case, even in the absence of the impressive candidate, because I like the voting booth. We need to establish the dependence of X on Z. However, actual evidence can provide us with candidates for Z.

2. Consider principles and regularities that describe the phenomena under interest. These might come from social or natural sciences or from other considerations (here we might rely on expert judgement is nothing else is left). For example, we might reason that Einstein’s work does explain the change in beliefs because we know that, in general, scientists are good in reflecting their own system of beliefs (assume this for the sake of the illustration) and a diary describing the cause of the change of belief is therefore sufficient to establish the impact. In some cases, we might question the dependency. For example, we might know that I watched many political debates and that people who follow these debates are very likely to vote. Therefore, the reasoning continues, the impressive candidate did not (probably) affect my voting; had the candidate been absent, I would still have voted. In these cases, the plausibility of the counterfactual depends on the plausibility of the underlying principles.

3. Consider theoretical structures that are purported to explain the phenomena. For example, we could rely on philosophical investigations on the importance of explanatory relevance in science to reason that it was Einstein’s explanation of the Brownian motion that was relevant in the change of beliefs. Someone else (sociologically oriented) could argue that it was the fact that Einstein explained (and not the explanation itself) that made a difference to the beliefs.

Such “philosophical” theories are difficult to compare with respect to their adequacy. Of course, there are considerations that are relevant in establishing the merits of different theories (theoretical progress is possible) but conclusive results are difficult to achieve. Therefore, historical counterfactual cannot be established with certainty. However, it does not follow that they are futile. Our knowledge is always fallible, but it does not follow that it is therefore futile. Moreover, the steps 1 and 2 above are able to limit the number of philosophical considerations that are relevant in counterfactual reasoning. Actual evidence matters. We do not drown in an endless see of philosophical pondering. Rather, we can debate the philosophical questions that remain once we have narrowed down the relevant consideration in each case. (See my 2018 paper.)

We see that historical counterfactuals can be assessed only in the light of theoretical structures. If we approach possible futures with the help of structural taxonomies, the possible futures can be analyzed in the same way as historical counterfactuals. While evidence of possible futures is more difficult to come by than evidence of the past and therefore the narrowing down of relevant considerations in deciding the most plausible futures is more difficult that in the case of history, the taxonomies enable us to see what kind of evidence could be helpful and what the space of possibilities looks like.

6 thoughts on “Theoretical-Structural Taxonomies in History and Future”