When I was around 14, my math teacher T. M. always accused me of excessive speculation. I decided that I would learn everything there is to be learned about the art of speculation. I went to the library and starter to read Tetlock and Belkin’s Counterfactual Thought Experiments in World Politics in order to counter my teacher’s accusation… Well I did not. But I would have read the book, had I known it exists!

Counterfactuals, counterfactuals, counterfactuals. In this post, I discuss further historical counterfactuals by writing a kind of commentary on Tetlock and Belkin’s Six Criteria for Judging Counterfactual Arguments (a section in Tetlock and Belkin 1996). Tetlock and Belkin often use the notion of counterfactual thought experiment and I will follow this usage even though I do not think that “thought experiment” captures the nature of counterfactual reasoning.

1. Clarity: Specify and circumscribe the independent and dependent variables (the hypothesized antecedent and consequent).

By this criterion, Tetlock and Belkin mean that thought experiments should manipulate one cause at a time. The problem is that it is difficult to hold “all things equal” when we perform thought experiments. Even though Tetlock and Belkin are not explicit on the issue, there seems to be two versions of the problem.

(I) Changing the value of a variable X in a way W; then W has some consequences to the system that are independent of X. For example, I ate oatmeal. What would have happened if there was not oatmeal in my kitchen? Had I eaten bread or nothing? It depends on how the oatmeal is removed in the scenario. Had there not been oatmeal because I did not go to a grocery store, there probably would not have been bread either. On the other hand, had the lack of oatmeal been caused by my kids eating all of it, then I would have eaten bread.

I do not find this worry too serious. If we are interested in how a change in X would have affected Y, then we focus on a scenario where X is changed in a way W that has no effect on Y. For example, we simply remove the oatmeal from my kitchen. I think there are two issues that lead to confusions and make (I) look like a serious worry.

(a) The question “Had X been differently, what would have happened to Y” is confused with the question “In the most likely circumstances where X was differently, what would have happened to Y”. We do not think it is likely that someone just hides my oatmeal. It is more likely that I did not buy groceries. However, the confusion is still acute because the antecedent of the second question is not about a counterfactual situation where X is differently. Instead, it is literally about the most likely circumstances (c) where X is differently (“Had c been the case, what would have happened to Y?). To see the problem, in addition to the confusion, we can note that this leads to a regress. If we wanted to know what would have happened had c been the case, we would need to know the most likely circumstances c* where c was the case and ask what would have happened, had c* been the case, ad infinitum.

(b) We worry that it is impossible to change X in a way that does not in itself have effect on Y. For example, suddenly removing oatmeal from my kitchen could make me paranoid and I could end up in a hospital. However, these scenarios assume that the connection between X and Y is a complex one. The problem is not that W has an independent effect on the system, but that X is in a complex relationship between Y. For example, the lack of oatmeal causes the belief “I need to eat something else” and the belief “something strange is happening because the oatmeal disappeared”. They both have an effect what happens next. Let’s discuss this topic next, as the second version of our initial problem is that

(II) The change in X has so many consequences that we are unable to track every causal path and therefore it is impossible to say what would happen to Y.

This is mainly an epistemological problem and does not concern the possibility of formulating counterfactual scenarios where only one variable is change at a time. However, there are still some complications.

First, consider the following schema:

In these cases, X has a direct and indirect effect on Y. In general, such cases can be broken into its compound parts and we can evaluate the relationship between X and Y by fixing Z; the relationship between Z and Y; and relationship between X and Z. The total effect of X on Y can be decided on the basis of the more basic relationships.

In some cases where we ask “What would happen to Y, had X been differently?”, we want to hold Z fixed and in other cases not. For example, we can understand the dynamics of the western front of WW1 by noting that there was not much to do for either side: Every offensive (X) was countered by the other side (Z) and the positions remained the same. However, we sometimes want to know what would have happened, had Z been fixed. For example, we could wonder what would have happened to Finland had there been no Winter War but had Finland still allied with Germany. There is no general rule for which of these of counterfactuals – fixed or unfixed – are better. As long as we specify in which category a case at hand belongs, both can be interesting.

However, the fixing of Z is especially important and should be in place to counter the “surrealism-whining” where every counterfactual claim is doubted because the change in the antecedent requires something out of ordinary (a miracle, an intervention or whatever). The idea that I would become paranoid had the oatmeal been missing is one example (see above). It is clearly true that “had there not been oatmeal, I would have eaten bread”, given how my kitchen was and given my preferences for breakfast. Every non-surrealist accepts this. In order to get the right verdict, we need to say “had there not been oatmeal and had my belief-system been balanced [I forgot that there was oatmeal before] then I would have eaten bread”. In other words, we need to fix everything that is merely a consequence of the possible world at hand being surreal i.e. one where counterfactuals are true (a world with small miracles, interventions etc.). When we discuss what a morning without oatmeal would look like, we are not discussing how crazy the world would be had the oatmeal been missing.

If we iterate the schema above, we get the following schema.

It becomes easy to notice that at some point “bottom-up” approach to counterfactual scenarios becomes practically impossible, i.e. we cannot decide what would have happened to Y, had X been differently, by tracking the direct relationships between the variables. This is, again, mainly an epistemological problem and we return to it later. Yet, two things should be noted.

(i) Sometimes we might end up formulating counterfactual scenarios with a vague structure. In complex systems, we might not be able to specify which effects of X we want to fix when we ask “What would have happened to Y, had X been differently” simply because we do not know all the effects of X. For example, we might wonder what would have happened had there been no Winter War, what would have happened to Finland in 1940’s. Do we assume that Finland allied with Germany anyway? Do we assume that Finland ceded territories to the Soviet Union? If such factors are not specified, then we might end up in confusion with respect to the kind of counterfactual question we are asking.

(ii) In the case of complex systems, it becomes difficult to connect the evidence from the actual world to counterfactual scenarios. If we create a scenario where many effects of X remain fixed while X changes, and if the actual historical systems where a factor of the same type as X is present always have those effect, then the more we fix, the more difficult it becomes to find evidence for the counterfactual scenario.

2. Logical consistency or cotenability. Specify connecting principles that link the antecedent with the consequent and that are cotenable with each other and with the antecedent.

There are some problems with this criterion. First of all, it does not seem correct to require that the antecedent must be consistent with the connecting principles. “Had Einstein not explained Brownian motion, scientist would not have believed in atoms” is a good explanatory counterfactual. The connecting principle is that scientists give ontological weight to entities that have explanatory power. Given this principle, it might seem unlikely that there was no explanation for Brownian motion. Surely, the importance (personal or institutional) of explanatory work was an incentive for Einstein’s work. Yet, it is perfectly meaningful – and even necessary – to ask what would have happened without there being an explanation.

Take an even simpler example. The number of cells in a bacteria culture doubles every hour. First there were 1000 bacteria, then 2000, then 4000 etc. Then we ask what would have happened had there been 8000 bacteria instead of 4000; and we can easily tell that next there would have been 16000 bacteria. It is of course impossible for there to be 8000 bacteria, given the rate of growth, but the counterfactual statement is still clear and tractable.

An example that Tetlock and Belkin refer to is the following.

“The best known example is John Elster’s critique of Robert Fogel’s counterfactual assertion that “if the railroads had not existed, the American economy in the 19th century would have grown only slightly more slowly than it actually did. Elster did not show that Fogel was wrong but he did show that it is nonsensical to postulate as a supportive connecting principle that the internal combustion engine would have been invented earlier in America without railroads because the postulate presupposes a theory of technical innovation that undercuts the original antecedent. If we have a theory of innovation that requires the invention of cars 50 years earlier, why does it not also require the invention of railroads?“

I think it is a mistake to think that a good counterfactual scenario is one where the antecedent is false because the possible world is one where our theories do not hold. We are not interested in such surreal worlds. Rather, we are interested in scenarios where the antecedent is changed with surgical intervention and where the theories of ours are still true. Only by assuming the theories that describe the actual world we can have any use for counterfactuals. A car hit a wall 100km/h. Had it hit the wall 40km/h, nobody would have been hurt. The later counterfactual scenario is assuming that the laws of physics are the same and the lower speed was due to the decision of the driver (for example). In this way, it can give an insight how to drive in the future. Of course, we are not assuming that the speed was 40km/h because the laws of physics were different.

Secondly, while I think it is clear that the connecting principles must be consistent with each other and that they should link the antecedent with the consequent, there are still issues that require attention. We can distinguish two different approaches to counterfactual scenarios.

(I) We can take some X and some Y and assume that X would have led to Y. Then we attempt to explicate what principles are required for the connection to exist. This is a bottom-up strategy in counterfactual tracking.

(II) We can take the principles P that some theory uses to describe the domain of X and Y. Then we ask “given that X happened and given P, would Y happen”. This is a top-down strategy in counterfactual tracking.

Strategy (I) is useful when we attempt to establish the connection between X and Y (for an explanation, for example) or if we have some reason to believe that the connection exists even though we are unable to formulate the connecting principles. For example, we might suspect that Einstein’s work on Brownian motion explains the belief in atoms and attempt to make sense on the principle that grounds the explanatory relation; or we might know that scientists mentioned Einstein’s work as a reason for their beliefs.

Strategy (II) is useful when we create taxonomies of possible pasts and futures. We are not interested in the connection between X and Y per se but in mapping the past and futures that X could (have) create(d) according to our theories. Y could be some interesting endpoint and therefore we ask the question about X and P with respect to Y. For example, we could assume that structural realists’ picture of science is correct. Then we could ask “Given the realists’ picture and given a new accelerator, could there be a fundamental change in science”. This would give us a map of a possible (from the realists’ point of view) futures once we investigate the relationship between structural realism and the current situation in experimental physics.

As a final note, the principles and theoretical frameworks and how to establish them are the core question in counterfactual reasoning, as I have argued in previous posts. It is not enough that the principles in each case are mutually compatible. They should also be credible. The criterion of cotenability is a rather minimal one. We come back to this soon.

3. Historical consistency (minimal-rewrite rule). Specify antecedents that require altering as few “well-established” historical facts as possible.

The idea in this criterion is to exclude counterfactual scenarios like one where Napoleon has missiles. It is too far-fetched, to argument goes, to assume such thing from the point of view of historical relevance.

In Virmajoki (2020), I have argued that this rule is not universal. If it is true that “Had X been differently, Y would have been differently” then X explains Y and the counterfactual is important even if the change in X is far-fetched.

However, as I noted in a previous post, the rule serves two different functions in the counterfactual account of historiographical explanation. First, the minimal-rewrite rule is a useful methodological rule. It might be too difficult to evaluate a counterfactual citing a far-fetched change in history because we have no cases to which we could compare the counterfactual. Secondly, the minimal-rewrite rule is directly connected to the issue of historical contingency. If a historiographical explanation is requested to show the contingency of events, as is sometimes argued, then the minimal-rewrite rule guarantees that we are able to show exactly that.

4. Theoretical consistency. Articulate connecting principles that are consistent with “well-established” theoretical generalizations relevant to the antecedent-consequent link.

It is obvious that we need theoretical knowledge or at least generalizations to “get the counterfactual scenarios going”. How such knowledge can be produced and used is too difficult question to tackled here. However, (at least) the following issues are interesting:

(i) How can we extract theoretical knowledge from the history and test that knowledge against history? One could argue that generalizations in social and human sciences have a complex relationship between the actual history (involving idealization, simplification, the difficulties of testing etc.) and therefore the relationship between those theories and counterfactual histories is not one of “copy and apply”.

(ii) What is the role of normativity in the theoretical understanding? When and why would we like to describe desirable/undesirable pasts? Do we want to build a continuum from best-case-counterfactuals to worst-case counterfactuals?

(iii) How universal are historical explanations? Do we sometimes need to refer to local principles that governed a historical situation? If so, how are those local principles known?

In a previous post, I have touched these issue. There I suggested that we need to create taxonomies of counterfactual histories with the help of different theories. Here is a rather funny coincidence. After listing different theories that scholars have used in their counterfactual scenarios, Tetlock and Belkin remark that “This overview is, however, disturbing. It suggests that each school of thought can foster its own favorite set of supporting counterfactuals” (1996, 27). I do not find the situation disturbing. Taxonomies of possible histories and futures provide us with resilience because of their built-in pluralism. Furthermore, I think that we can, to some extent, evaluate the relative merits and credibility of different theories. However, I think it is somewhat naïve to expect that we could test counterfactuals directly by stimulating predictions or comparing them with (old or new data), as Tetlock and Belkin suggest (1996, 27). I now turn to these issues.

5. Statistical consistency. Articulate connecting principles that are consistent with “well-established” statistical generalizations relevant to the antecedent-consequent link.

I think it is obvious that the theoretical knowledge that supports counterfactual scenarios can be statistical in nature. Given that counterfactual scenarios are difficult to track and almost always end up in a judgement “Had… Y would probably been the case”, the statistical nature of some links does not bring any new problems to the basic dynamics of counterfactual reasoning.

There also seems to be a deeper strategy here. It seems that a hidden assumption here is that some “schools of thought” (see above) would fail statistical tests and therefore be excluded from counterfactual reasoning. However, it is somewhat unclear how to test social and human sciences statistically. Surely, we can test them in the sense that we say that there is too little data or that the data is too difficult interpret. For example, Tetlock and Belkin point out that the democratic-peace hypothesis, which has been used in a counterfactual scenario, has been criticized on various grounds ranging from statistical samples to definitions and problems created by confounding variables (1996, 29). However, if we need to exclude all theories because they are not adequately supported, then we need to abandon all counterfactual reasoning. The problem was supposed to be how to identify the adequate theories and not how to get rid of all theories.

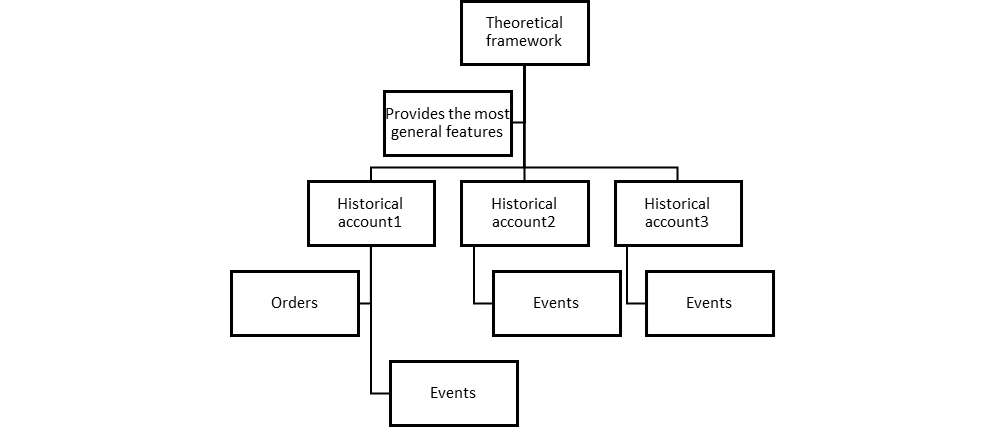

In general, it is unclear whether theoretical frameworks in human and social sciences should be understood as straightforward descriptions of how the details of history went. A more fruitful suggestion could be that they are higher-order interpretative frameworks that give historical accounts their general features, as suggested here.

6. Projectability. Tease out testable implications of the connecting principles and determine whether those hypotheses are consistent with additional real-world observations.

Tetlock and Belkin suggest that we exclude accidental generalization from principles that are used in counterfactual scenarios. As a first approximation, accidental generalizations are generalizations that hold only in specific actual conditions. That I have only Adidas shirts is an accidental generalization. Had someone gave me one bought from a Nike store, it would no longer be true. The problem is how to characterize accidentality. One suggestion is that an accidental generalization would not have held, had there been a change in background conditions. In addition to the unclarity of this definition, the problem is that it has a counterfactual form. If we are wondering which generalizations can be used in counterfactual scenarios, it might not be a good idea to refer to counterfactual scenarios in the criteria.

The obvious way out is to require that generalizations need to survive testing of some sort in order to be used in counterfactual reasoning. But what would those tests look like?

The first option is to draw predictions from the principles and see whether the predictions are true. There are problems with this suggestion.

(a) It is a well-known fact that few generalizations alone cannot provide us with predictions – even in natural sciences[1]. In addition, we need auxiliary hypothesis. When a prediction fails, the problem can be either in the generalization or in auxiliary hypothesis. Given the difficulty of performing experiments in social and human science and given the long duration of historical processes, the prediction-based exclusion of generalizations will be a painful process.

(b) Given that we need to estimate the possible futures now, we do not have the time to wait that the prediction-based testing is completed. The intellectual problem of achieving knowledge in social and human sciences is also an existential problem of how to prepare for the future. The generalizations that are used in counterfactual scenarios are generalizations that can be used to estimate the futures (if they were not, the ability to make true predictions would be irrelevant to their truth). Surely, we need to improve our knowledge once we see how the future develops, but the problem of how to estimate the future cannot be postponed for the unforeseeable future.

(c) In future, there will be new “schools of thought” that provide their own counterfactual scenarios. Even is we are able to exclude some schools and their principles and even if our knowledge improves in this process, we will still need to figure out what to do with the plurality of schools of thought and their counterfactual scenarios.

The second option is to develop further and systematize our knowledge of the past. However, gaining insights from historical cases is an extremely difficult task, as I have discussed in a previous post. To simplify, historiographical accounts (i.e. the “results of historians”) and the interpretations of their consequences for a some general topic are theory-laden[2] and the history itself might change too much from period to period for there to be any neat set of generalizations that capture it. And given the complexity of history and its changes, the use of historical knowledge in counterfactual scenarios becomes difficult and allows different interpretations.

As a response to these problems, I suggest again that we need to learn to live with theoretical pluralism rather than get rid of it. We need to provide taxonomies of counterfactual pasts and possible futures as suggested in previous posts. To sum up, these taxonomies are based on theoretical frameworks (“schools of thought”) which provides the most general features of counterfactual scenarios. Within these frameworks, there can be different counterfactual reconsturction of the past (different orderings of events and their causal relationships) which all accord to the basic tenets of the theoretical framework. Given such taxonomies, we can see at a glance the space of possible histories (and futures) that our current theoretical knowledge allows and enables us to identify points that require further development.

Conclusion

In 1996, Tetlock and Belkin formulated six important criteria for judging counterfactual arguments. Although we had to make some adjustments to the criteria, the criteria capture the core of sound and interesting counterfactual reasoning.

There is, however, one important difference between 1996 and 2020. Tetlock and Belkin suggested a bipartite system of counterfactual reasoning (consisting of a counterfactual antecedent and a set of principles) where the goal is to tell what would have happened, had X not been the case, on the basis of the best available principles connecting X and its consequent. On the other hand, I suggest that we adopt a tripartite system (consisting of a counterfactual antecedent, theoretical frameworks and principles derived from the frameworks) where the goal is to map a set of possible histories where X is not the case on the basis of principles that stem from theoretical frameworks.

References

Tetlock P & Belkin, A. (1996). “Counterfactual Thought Experiments in World Politics: Logical, Methodological and Psychological Perspectives”. (In the book with the same name).

Virmajoki, Veli (2020) “What Should We Require from an Account of Explanation in Historiography?”. Journal of the Philosophy of History.

[1] Newton’s theory predicted wrong orbit for Uranus because Neptune was not known to exist and affect the orbit of Uranus.

[2] The point is not that the historians add some extra-layer of theories to otherwise objective historiography. Rather, the point is that historiography does not get off the without theoretical assumptions.

2 thoughts on “Squeezing Water out of Stones. On Historical Counterfactuals”