The Electoral Consequences of Economic Inequality in Finland: The Case of the Finns Party

Hector Bahamonde and Aki Koivula

INVEST Blog 7/2023

It is not new to social scientists that economic downturns affect voting decisions. Thus, since politics is the realm where decisions are made about “who gets what, when, and how,” the unemployment rate, economic growth and income distribution will inevitably influence people’s minds when it comes to voting.

In Finland, income inequality has become “the new norm”. Over the past 20 years, income inequality has remained relatively stable. However, in this case, the lack of change is cause for concern: the political system has been unable to address economic increase by reducing inequality levels to those of 25 years ago.

Why does it matter?

Economic inequality has emerged as a wicked problem with far-reaching political consequences. Political scientists have long understood that political parties capitalize these economic grievances to obtain electoral advantages. This is by no means negative phenonmen. More on the contrary, parties represent social interests – hopefully – and aim to address these grievances through policies.

However, it has been suggested that inequality is the driving force behind the rise of populist parties, as seen developments in countries such as Brazil, the United States, France, and Italy, among others. In Finland, however, research on this topic has been limited. Therefore, we are introducing a new research project that explores the relationship between the evolution of economic inequality in Finland and the electoral support of the Finns Party (FP), the Finnish populist party.

The relationship between inequality and support for the FP is intriguing

Previous studies have shown that the party does not align itself directly with any of the traditional social divisions. Originating from the Finnish Rural Party, the FP has traditionally supported farmers and opposed the elite classes, combining conservative social values with centrist economic policies. The party has expressed distrust towards established political parties and the European Union. In recent years, more radical right-wing views on issues such as feminism and immigration have also gained popularity among the party’s supporters and candidates.

Although a significant proportion of the working class has supported the FP since the 2010s, the attitudes of FP voters towards income distribution do not align with traditional leftist views. Instead, the party fits better into a new socio-cultural cleavage as it has gained support from a cultural backlash that promotes traditional values and stricter immigration policies.

Furthermore, previous research indicates that there is no direct relationship between support for the Finns and low individual-level income. In fact, post-parliamentary election surveys reveal a highly diverse support base for the FP, with varying demographic factors such as education, occupation, and region (Westinen et al., 2020).

However, previous studies do suggest that growing economic insecurity at the regional level is a crucial factor in explaining support for the FP (Wass & Kauppinen, 2020). This pattern is observed in regions where a decline in earned income predicts an increase in the party’s support. Similarly, Patana’s (2020) research indicates that regional unemployment and social assistance are positively associated with support for the FP.

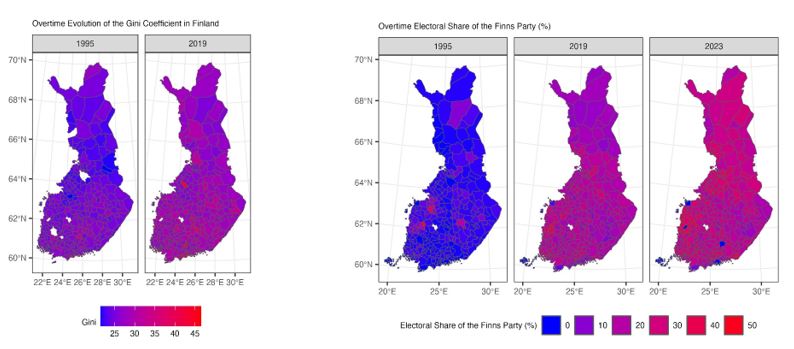

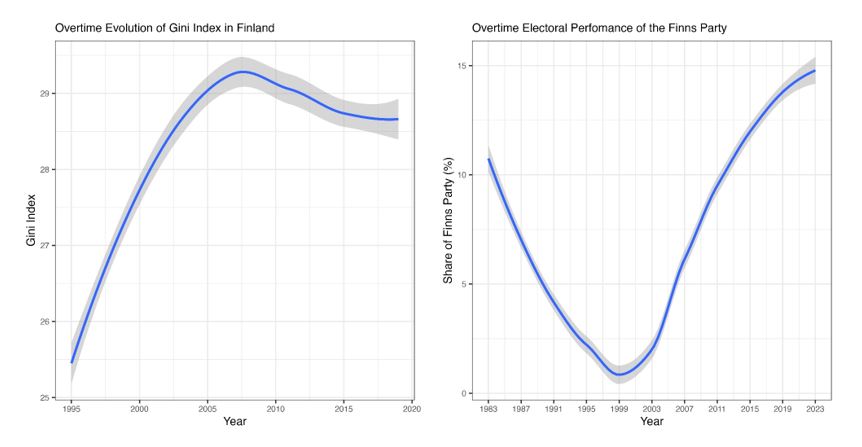

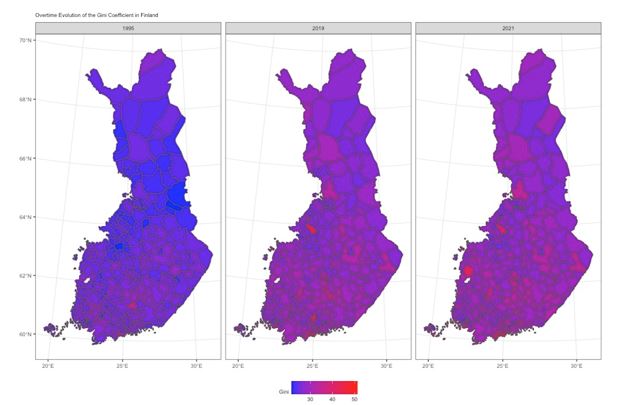

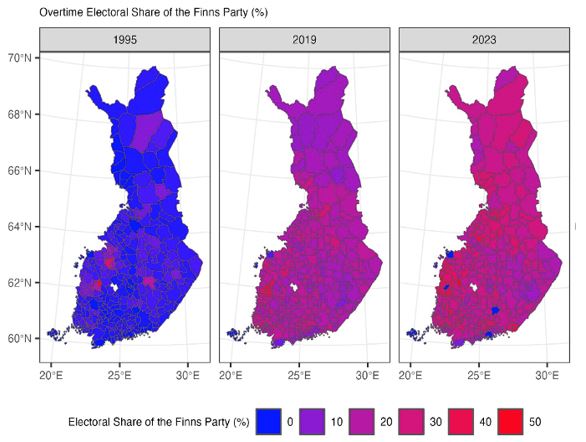

As Figure 1 conveys, there seems to be a strong association between income inequality and the ever-increasing electoral support of the FP. In fact, if we map the evolution of these two social processes, we clearly see the way in which both phenomena are spatially distributed (see Figure 2a and Figure 2b) look closely related to each other.

One way to understand these maps is as if they represented temperature. The heatmaps in Figure 2a represent how much inequality there is in Finland, and how it has evolved over time. The heatmaps in Figure 2b show how dense the electoral victories of the FP have been. We can clearly see that things have become much “hotter,” meaning that since 1995 Finland has become a more unequal country. In parallel, it has become a society that shows increasingly higher levels of adherence to populist ideas.

There has been a growing discussion in Finland regarding the “revenge of the places that don’t matter” (e.g., Harjanne, 2023). As can be seen in Figure 2, in the 2023 elections, the FP won several new areas, especially in Northern Finland. It seems that the FP has won support from the traditionally strong “region party,” namely, The Centre Party of Finland, in rural and village areas, signaling significant changes at the regional level and dissatisfaction with the previous political incumbents.

The experience of inequality at the regional level goes beyond an individual’s own economic situation; it represents a comprehensive experience of the direction in which one’s living environment is evolving, impacting future prospects and opportunities (Rodriguez-Pose, 2018). When inequality increases in a region, the middle class shrinks, services decline and fewer individuals have a chance to succeed in life.

Why?

The intertwined relationship between populism and inequality is worth explaining in detail. We are working on a series of hypotheses to explain the association between inequality and the support for populist parties. Our leading hypothesis is that populist parties (and not only in Finland) are able to capitalize the dissatisfaction with the economic system, particularly, by blaming traditional parties. This way, populist parties like the Finns Party, build a political rhetoric based on the “us vs. them,” which places them in an advantaged position to target mainstream political, social and economic elites. Thus, as we explain, inequality gives populist parties a great opportunity to position themselves as the “only” viable solution to address issues such as inequality, in a way that other (mainstream) political forces have failed to implement.

Moreover, we believe that demographic development, globalisation and labour market changes play a marjo role in the relationship between voting for populist parties and inequality. Populist parties, for example, seek to restrict immigration on the grounds that it protects the welfare system. Additionally, populist parties accuse traditional left parties of failing to protect the working and middle classes from phenomena such as automation, where advanced mechanical and automated processes increasingly replace an aging working population.

All in all, populist parties have a built-in advantage that thrives during times of inequality and economic vulnerability. Their usual promise of economic and cultural restoration strongly resonates in the ears and minds of the economically, socially and culturally displaced, that is, the working and the middle classes. Artificial intelligence is also the newest technological development that possibly threatens the middle-class and also an important number of white-collar occupations.

In order to account for the dynamics of the Finns’ voting over time, we have already started preparing modelling methods based on a longitudinal design. In fact, the preliminary work presented in Figure 3 shows that as inequality increases, the proportion of votes of the Finns Party increases steadily. This type of methods and data effectively allow the researchers to establish a causal relationship between the two phenomena.

To conclude, we continue developing relevant research that aims at contributing our understanding of the electoral consequences of economic inequality in Finland. We believe that a better understanding of the possible long-lasting consequences of inequality is helpful at times when populist parties thrive in the polls. Overall, we hope that our research will contribute to a more informed and nuanced public discourse on economic inequality and its political consequences. By shedding light on the dynamics of party support, we believe that can help to inform policy decisions and promote a more inclusive and equitable society.

References

Harjanne, A. (2023) Alueiden kosto iski Suomen poliittiselle kartalle. Verde 10.4.2023: https://verdelehti.fi/2023/04/10/alueiden-kosto-iski-suomen-poliittiselle-kartalle/

Patana, P. (2020). Changes in local context and electoral support for the populist radical right: Evidence from Finland. Party Politics, 26(6), 718-729.

Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge journal of regions, economy and society, 11(1), 18

Wass, H., & Kauppinen, T. (2020). Palkkakuitti äänestyslippuna: tulojen yhteys äänestysaktiivisuuteen ja puoluevalintaan. In Mattila, M. (eds) Eriarvoisuuden tila Suomessa 2020. Kalevi Sorsa Foundation: Helsinki

Westinen, J., Pitkänen, V., & Kestilä-Kekkonen, E. (2020). Perussuomalaisten äänestäjäkunnan muutos 2011–2019. In Borg, S., Kestilä-Kekkonen, E., Wass, H. (eds.) Politiikan ilmastonmuutos: Eduskuntavaalitutkimus 2019 (pp. 307-331). Oikeusministeriö: Helsinki

Authors

Hector Bahamonde is a Senior Researcher at the INVEST Research Flagship Center of the University of Turku, Finland and also a Research Director of the INVEST-Hub about experimental research and interventions. He’s primary subfield is the political economy of inequality, political development and clientelism.

Aki Koivula is a Senior Researcher at the INVEST Research Flagship Center of the University of Turku, Finland. He’s research expertise consists of digital interaction and participation, social networks, trust, media consumption, political parties and social impacts of COVID-19.

Author names are in alphabetical order. Both of them contributed equally to this piece.