How Mothers’ Individual Psychological Flexibility Shapes Children’s Anxiety

Only-Child vs. Multi-Child Families

Bingkun zhang

Anxiety starts young

Preschoolers are in a rapid phase of development. Their emotions fluctuate more than adults’, and stress or conflict can more easily trigger anxiety. Anxiety ranges from worry and unease to fear or even intense fear, sometimes accompanied by bodily tension like a racing heart or tummy aches.

Common faces of preschool anxiety include separation anxiety, social fear, fear of physical harm, obsessive–compulsive symptoms, and generalized anxiety.

When anxiety becomes excessive and persistent, it can impair social skills, school adjustment, and peer relations—showing up as restlessness, inattention, school refusal, social avoidance, and repetitive/compulsive behaviors. Without timely support, anxiety that appears in the preschool years can persist into adolescence and adulthood.

A closer look at mothers’ psychological flexibility

Psychological flexibility is an important aspect of mental health and originates from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), a behavioral therapy based on functional contextualism and Relational Frame Theory.

Individuals with higher psychological flexibility are better able to stay aware, accept difficult emotions, and act in line with their values, and as a result they respond to problems and changes more calmly and effectively.

Research shows that when a mother’s individual psychological flexibility is lower, her parental psychological flexibility also tends to be lower.

In everyday interactions, she is less able to notice and accept negative emotions and tends to adopt more ineffective parenting behaviors such as control or avoidance, thereby leading preschool children to experience more anxiety.

Only-child vs. multi-child: does the PF–anxiety link change?

In the process of raising an only child, mothers may show more control and interference rather than accepting the child’s autonomy, causing the child to develop stronger dependence and poorer independence, which adversely affects psychological and behavioral outcomes and leads to greater anxiety.

In raising non–only children, mothers may display more neglect and differential treatment, and non–only children need to compete with siblings for parents’ love and attention, thereby developing more inferiority and anxiety.

These dynamics could shape how strongly maternal individual psychological flexibility relates to children’s anxiety.

Our research questions

- Are anxiety levels different between preschoolers in only-child and multi-child families?

- Is lower maternal individual psychological flexibility linked to higher child anxiety in both family types?

- Does sibling status change the strength of the psychological flexibility–anxiety link — i.e., is the association different in only-child vs. multi-child families?

How we studied it

Between April and September 2021, we invited 387 mothers of preschool children (aged 3–7) from Beijing, Shanxi, and Guangdong provinces in China to complete questionnaires assessing mothers’ individual psychological flexibility and children’s anxiety. Of these families, 185 were raising an only child and 202 had children with siblings.

What we found

We did not find an overall difference in average anxiety between only-child and non–only-child groups.

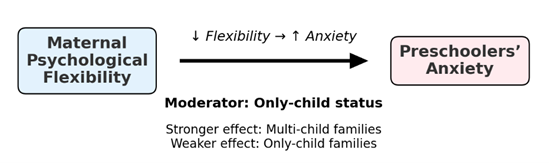

However, the association between maternal individual psychological flexibility and children’s anxiety depended on whether the child had siblings.

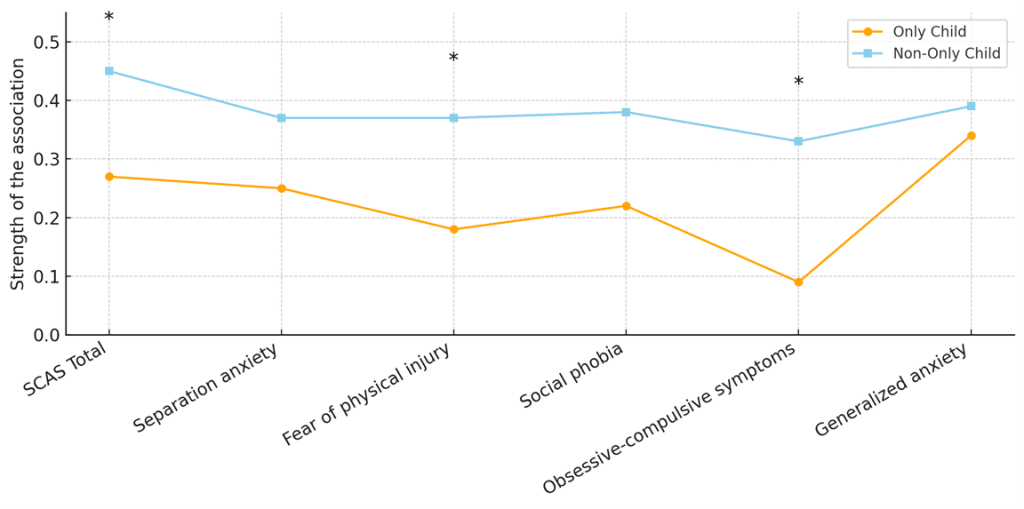

For children in only-child families, lower maternal individual psychological flexibility was associated with higher total anxiety and with four dimensions of anxiety: separation anxiety, fear of physical harm, social fear, and generalized anxiety.

For children in multi-child families, lower maternal individual psychological flexibility was associated with higher total anxiety and with all five dimensions of anxiety.

Having siblings changed the strength of the association. The association between lower maternal individual psychological flexibility and higher child anxiety was stronger in non–only-child families than in only-child families.

Put simply: when maternal individual psychological flexibility was lower, children’s anxiety rose more sharply in families with siblings. (This was evident for total anxiety and for specific dimensions such as fear of physical harm and obsessive–compulsive/impulsive symptoms.) (See Figure 1)

Why siblings matter

Only children often have more family resources than non–only children and can receive their mother’s full attention and care, making them more likely to develop personality traits such as being more self-centered and having lower acceptance of others; whereas non–only children need to compete with siblings for their mother’s attention and care, thereby developing an ability to read others’ cues.

When mothers with low individual PF adopt avoidance and overly emotional reactions in parenting, non–only children may perceive this more readily than only children and respond more sensitively. This helps explain the stronger association between low maternal individual PF and children’s anxiety in multi-child families (Figure 2).

Why this matters for families and society

Helping parents helps children. Supporting mothers in developing psychological flexibility can reduce the risk of childhood anxiety.

Multi-child families may need extra attention. Parenting programs should consider the specific challenges that come with raising siblings.

Looking forward

Before joining INVEST, I conducted this study. At INVEST, we have completed and are currently conducting work on multiple factors related to mothers’ parental PF. Looking ahead, we aim to co-design simple, easy-to-learn online and in-person self-help supports for parents—helping them enhance and sustain individual PF and parental PF, create family environments more conducive to children’s development, and give children a more resilient start in life.

This study was originally published in the Chinese Mental Health Journal (2022) and presented at the European Conference on Developmental Psychology (ECDP) in 2025.

Zhang B.K., Fan C.L., Wang L.G., Tao T. & Gao W.B. (2022). Relationship between anxiety of preschoolers and psychological flexibility of their mothers. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 36(09), 780-785.

Author

Bingkun Zhang is a Doctoral Researcher studying parental psychological flexibility among Chinese mothers living in China and across multiple European countries. Her work examines both child outcomes and the key family predictors of parental psychological flexibility—including intergenerational emotional support, childhood trauma, family structure, and socioeconomic conditions. She is committed to advancing research that supports parents’ psychological wellbeing and strengthens nurturing family environments.

Leave a Reply