At least since Kuhn, the changing nature of science has become evident. The idea that “all of the concepts we use to discuss science are in constant flux” (Pitt 2001, 381) can be called Heraclitianism (following Bolinska & Martin 2019).

The lesson (from historians of science) is that science has taken (sometimes radically) different forms in the past, and we should appreciate this fact in our thinking about science.We should learn from the differences, not from the similarities. The changing nature of science is what interests us historically.

One consequence from Heraclitianism is that because science is a category that we use to describe current epistemological practices and because those practices did not exist in the past, we need to conclude that there was no science in the past (see Virmajoki 2019 arguing this). As Lorraine Daston puts it:

”Historians of premodern science grew increasingly skittish about calling what they studied science at all, and the word scientist when applied to Archimedes or Galileo set their teeth on edge.” (2009.)

It has been suggested that this means that historiography of science cannot exist as a distinct field of inquiry but collapses into historiography of knowledge or historiography of ideologies. I disagree. I have argued that historiography of science can be understood in present-centered terms.

The approach I offer is the present-centered (or simply presentist) approach to the history of science. From the presentist point of view, historiography of science is the study of the past practices that have led to the present science. Nick Tosh defines presentism: “Modern science has a causal history, and [historiography of science] could reasonably be structured around a causal backbone of past activities which helped to bring it into being.” (2003.)

The crucial question is the nature of causation in historiography. I take it that the conception of causation as difference-making[1] is well suited to historiography of science. In the difference-making conception of causation, “cause is something that makes a difference to its effects” (Menzies 2004, 139). This is not a novel suggestion. For example, Ben-Menahem has argued that “Historical analysis seeks to separate the factors that made a difference from those that did not” (2016, 374).

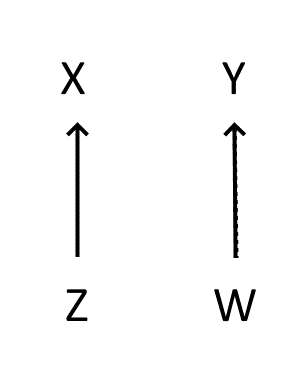

Consider an example:

Why did scientists come to believe that atoms exist (X) rather than believe that atoms do not exist (Y)?

Because Einstein formulated an explanation of the Brownian motion and Perrin confirmed this explanation with his experimental work (Z). Had there not been such explanation or experimental work (W), scientists would not believe in atoms.

I will not defend presentism in this post (see the defense in Virmajoki 2019). Rather, I will discuss the consequences of the presentist framework with the difference-making conception of causal explanation on philosophy of science.

It has been widely thought that philosophical theories of science must stand tests against the history of science in order to be accepted (see e.g. McAllister [2018, 239] and Donovan et al. [1988, 3–8]). An important consequence of presentism is that the testing of philosophical theories against the history of science is not a straightforward matter. In the presentist approach, a practice is a part of history of science if and only if it has been part of the causal history leading to the present science. Therefore, there are practices that are not scientific themselves but belong to the history of science. This means that studying these practices tell us not about the nature of science but how science came to be. It seems that we should not demand that our philosophical theories of science capture the nature of practices that were not scientific in the strict sense. This means that being a part of the history of science is not sufficient for a practice to serve as evidence for the philosophy of science. This may sound deeply problematic since it is usually being thought that the compatibility with the actual history of science is one of the best tests for the philosophical theories of science. If we lose this way of looking at the epistemology of philosophy of science, what is left?

First possible reaction: We can test a philosophical theory against a past practice even if that practice is not a scientific one (in the strict sense). It is sufficient that the past practice is similar to the present science (with respect to some relevant feature).

There are two problems in this suggestion.

- The number of cases available for the philosophy of science becomes much larger once we allow that philosophical theories can be evaluated against “scientific enough” historical episodes. The problem is that one could find evidence for almost any claim about science.

- The notion of relevant similarity seems to guarantee that there cannot be a genuine counterexample for one’s theory. If such a counterexample is suggested, one can always claim that the example is not a relevant historical episode.

What does a presentist have to offer?

We may question the fruitfulness of descriptive theories of science, i.e. theories that attempt to describe the actual workings of science[2]. Suppose we had a theory of science that captures many episodes in the history of science. It seems that we could still ask whether science should have developed in accordance with that theory.

Perhaps it could be more fruitful to ask what would have happened in the past, had science developed in accordance with some philosophical theory.

Counterfactual scenarios are always difficult to work with. However, as we have seen explanations in historiography of science have the form

(Actual) X rather than (counterfactual) Y, because (actual) Z rather than (counterfactual) W.

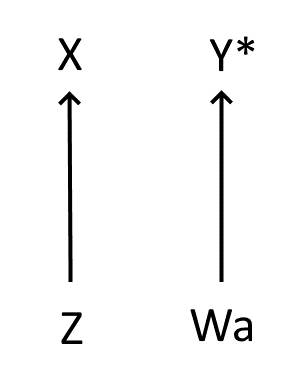

Testing philosophical theories against counterfactual scenarios is therefore a “mirror image” of explanations and therefore not in principle more challenging:

We ask “What would have happened, had Wa rather than Z been the case?” (the answer is “Y*”) and decide whether it would have been preferable that Y* was the case.

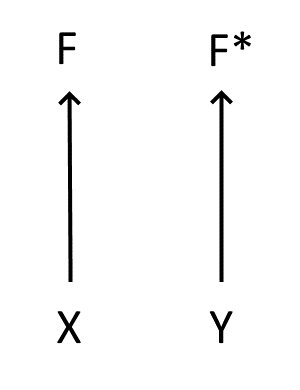

Such a counterfactual account of testing is most naturally suited for theories of scientific development. However, it is not limited to those theories. For example, in the philosophy of biology, there are arguments in favor of explanatory pluralism (e.g. Théry 2015; Mekios 2015). One common theme in such arguments is that some particular account of explanation does not capture some of the important explanatory practices of biology. These arguments seem to have the form (F):

Had scientists followed the philosophical account A, they would not have achieved some important (actual) results.

In general, there are many philosophical arguments that claim that some philosophical account does not capture the practices of scientists and they all seem to share the form F (lets call them F-claims). In fact, it seems that a commitment to an F-claim follows automatically from any argument that proceeds to show that certain philosophical account is not satisfactory. If the claim

(C1) Had scientist followed the account A, they would have achieved the same results as they actually did.

is true, then it is difficult to see what is wrong with the account A. Surely, it does not describe what actually happened but why should we prefer the actual course of events if some alternative would have led to the same outcome.

The presence of F-claims in wide variety of cases indicates that many philosophical debates have counterfactuals in their deep-structure. Once we notice this, an argument of the form F*:

(C2) Had scientists followed the philosophical account B, they would have achieved some important (counterfactual) results.

seems to be on par with “normal” philosophy of science. A counterfactual account of testing does not seem that exotic after all. (Compare C1 and C2.)

Moreover, counterfactuals are also needed in interpreting particular features of science.

For example, the divide et impera move of scientific realists has a modal aspect: “Theoretical constituents which make essential contributions to successes are those that have an indispensable role in their generation.” (Psillos 1999, 104 [emphasis added]). Our interpretation of the role of a theoretical constituent depends on what would have happened without that constituent. Also answering the question ”Could we have a different science?” requires counterfactual approach (see Virmajoki 2018).

Finally, notice that the estimation of the possible futures of science shares the same structure. If know what changes in the past would have led to a different science, we may be (at least sometimes) in the position to tell what changes (from X to Y) now or in the near future could lead to the future F*.

I conclude that the sciences we never had are, philosophically speaking, most interesting ones.

A science we never had

- could have taken us to a different present situation (historical explanation)

- could have produced preferable results (counterfactual testing)

- could be achievable in the future (estimation of the futures of science)

I recommend that we leave the world behind and fall in love with counterfactuals.

References

Beebee, Helen & Hitchcock Cristopher & Price, Huw. (2017). Making a Difference: Essays on the Philosophy of Causation. Oxford University Press.

Ben-Menahem, Yemima (2016). “If Counterfactuals Were Excluded from Historical Reasoning”. Journal of the Philosophy of History 10 (3). 370-381.

Bolinska, Agnes and Martin, Joseph D. (2019). “Negotiating History: Contingency, Canonicity, and Case Studies”. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science.

Daston, Lorraine (2009). ”Science Studies and the History of Science”. Critical Inquiry 35 (4). 798–813.

Donovan, Arthur & Laudan, Larry & Rachel Laudan (1988). Scrutinizing Science: Empirical Studies of Scientific Change. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Lewis, David (1986). ”Causation”. Philosophical Papers vol. II, Oxford: Oxford University Press. 159–213

McAllister, James W. (2018). “Using History as Evidence in Philosophy of Science: A Methodological Critique” Journal of the Philosophy of History 12 (2). 239–258.

Mekios, Constantinos (2015) ”Explanation in Systems Biology: Is It All About Mechanisms?” In Braillard, Pierre-Alain & Malaterre Christophe (eds.). Explanation in Biology. An Enquiry into the Diversity of Explanatory Patterns in the Life Sciences. Springer Netherlands. 47–72.

Menzies, Peter (2004). “Difference-making in context”. In J. Collins, N. Hall & L. Paul (eds.), Causation and Counterfactuals. MIT Press. 139-180.

Pitt, J. C. (2001). “The Dilemma of Case Studies: Toward a Heraclitian Philosophy of Science”. Perspectives on Science 9 (4). 373–382.

Psillos, Stathis (1999). Scientific Realism: How Science Tracks Truth. Routledge.

Théry, Frédérique (2015). Explaining in Contemporary Molecular Biology: Beyond Mechanisms. In Braillard, Pierre-Alain & Malaterre Christophe (eds.). Explanation in Biology. An Enquiry into the Diversity of Explanatory Patterns in the Life Sciences. Springer Netherlands. 113–133.

Tosh, Nick (2003). ”Anachronism and retrospective explanation: In defence of a present-centred history of science”. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 34A. 647–659.

[1] See Beebee & al. [2017]; Menzies [2004]; Lewis [1986]

[2] It would perhaps be better to talk about actualist theories of science. As we will see, I will suggest a theory that describes counterfactual workings of science.

2 thoughts on “How I Left the World behind and Fell in Love with Counterfactuals. A Counterfactual Account of Testing Philosophical Theories of Science”