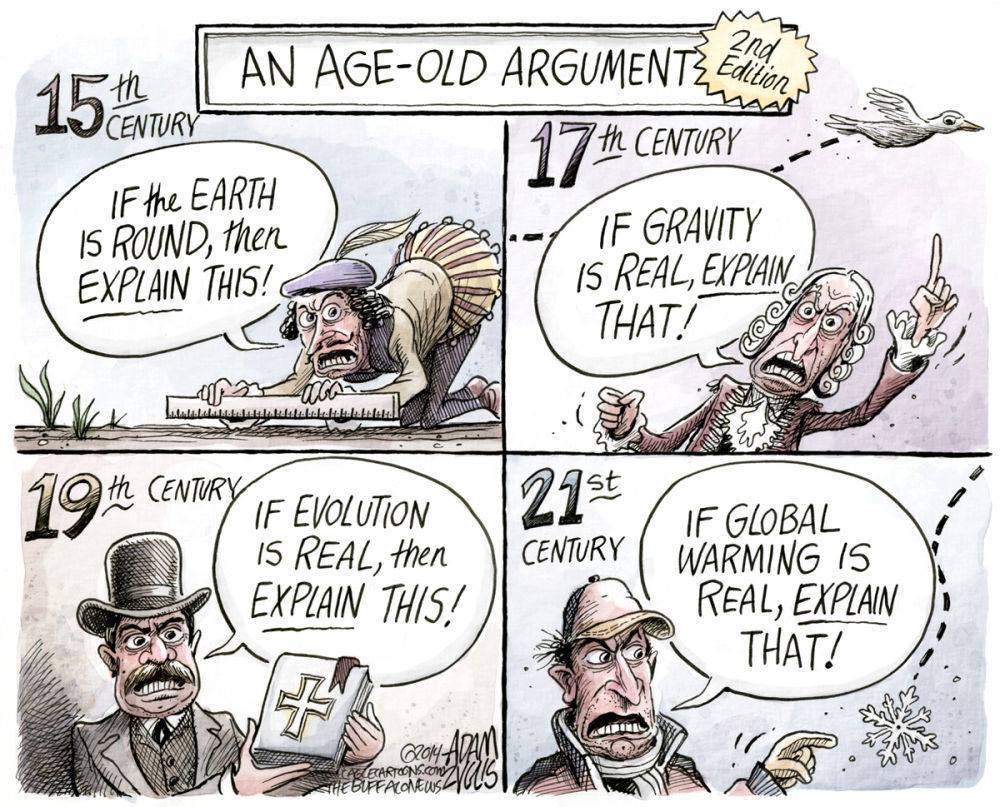

I have come across the following picture many times.

The picture involves a historical argument: There have always been explanation-seeking questions that appeared to refute a theory. Yet, the theory turned out to be successful. Conclusion: We can ignore certain explanation-seeking questions that appear to refute current beliefs.

Despite the good intentions, the argument is flawed. First of all, it is historically inaccurate. In the 15th century, there was no real scientific question about the roundness of the earth. In the 16th century, the problem was not why birds can fly despite the gravity. A better illustration would be someone asking “how can there be action-at-the-distance” i.e. how gravity can have an effect in the absence of local interactions. We can also note that even Aristotle posited “unnatural motion” caused by forces to explain why things that would naturally fall did not do so. It was never in doubt that some things naturally move towards the earth. In the 19th century, the explanatory problem Darwin’s theory faced was not that it could not explain the contents of the Bible. The problem was that Darwin’s theory initially explained only “old evidence”. This would be a problem even today. We usually consider as best those scientific theories that provide novel insights in phenomena that are not well understood.

In addition to historical distortion, the argument has a much deeper problem. Surely, scientific theories do not need to answer irrelevant or misleading explanation-seeking questions, but this does not mean that explanatory power is not important in theory-evaluation. Even if the history is full of explanation-seeking questions that seemed problematic but were answered (or explained away), this does not mean that we can ignore those questions. It only means that such questions are not knock-out-arguments against a theory. However, this much we already knew since there are no knock-out-arguments in science in general. Moreover, often the inability to explain a phenomenon does force changes in scientific theories. Newton’s theory, for example, could not explain the (amount of) precession of the orbit of Mercury, something that the General Theory of Relativity can explain. We can see that explanatory power is an important dimension of theory-evaluation that cannot be given up.

We can also notice that science is complex and deals with complex phenomena. It can explain (or explain away) phenomena that appear to contradict its surface-claims. For example, we can explain why earth appears flat in every-day life by citing its size and the properties of its surface. We can also explain how birds can fly by citing their anatomy and connecting it with what we know about forces. This surely involves a lot of knowledge and indicates how explanatory power increases the more complex our knowledge becomes. Simple answers do not satisfy our epistemic goals. We can also “explain away” the description of the universe by the Bible by citing the historical origins of the book.

It is important to find models of climate that have good amount of explanatory power. However, we should not expect these models to be simple and easy to use. As Parker (2018) points out

“Climate science, by contrast, aims to explain and predict the workings of a global climate system—encompassing the atmosphere, oceans, land surface, ice sheets and more—and it makes extensive use of both theoretical knowledge and mathematical modeling. In fact, the emergence of climate science is closely linked to the rise of digital computing, which made it possible to simulate the large-scale motions of the atmosphere and oceans using fluid dynamical equations that were otherwise intractable; these motions transport mass, heat, moisture and other quantities that shape paradigmatic climate variables, such as average surface temperature and rainfall. Today, complex computer models that represent a wide range of climate system processes are a mainstay of climate research.” [Emphasis added.]

Climate is a complex system and therefore our (explanatory) models will also be very complex. They should explain (and as far as I know, they in fact do) things like why some winters get colder. Such questions are not silly by any means. To ignore such questions as stupid is as bad a distortion of climate modeling as claiming that those question easily refute the climate science. There is no historical case where a sound scientific theory was able to explain all the relevant phenomena right away. There has to be a long phase of Kuhnian “normal science” where such explanations are formulated. To think that the climate science of our time has easy or complete answers to explanation-seeking questions can do real damage if we are not careful and fail to provide enough resources to improve that science. We need to make sure that the science has enough explanatory power. Even if we have the basics right and grounds for action, detail understanding can only be achieved by increasing the explanatory power.

In conclusion, I suggest we take seriously explanation-seeking questions and, what is equally important, explain away the view that such simple questions can refute complex science. The explanation-away must begin from the critical analysis of the simplistic presentations of the theory-observation relationship that are still widespread in the popular accounts of science. The simplistic ideas of science and its explanatory strategies do a lot of harm when we face complex scientific practices like climate modeling.

References

Parker, Wendy (2018). “Climate Science”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.