Consider the following claims:

(A) Had the weather been cloudy, Eddington would not have observed gravitational deflection in 1919.

(B) Had Eddington not been a pacifist, gravitational deflection would never have been observed.

Claim (A) implies that the weather was an explanatory cause of the observation in 1919, and claim (B) implies that the pacifism was an explanatory cause of the observation.

In order to justify these claims, we need to track down what would have happened, had the antecedents been the case. In other words, we have to construct scenarios where the antecedents are the case and see where those scenarios lead us.

The task of constructing scenarios is very different in the two cases.

Claim (A) is easily tracked. Given that we understand how light travels and is captured by photographic plates, we know that had there been more clouds, the observation could not have been the case. Had the clouds blocked the light, the moment of the eclipse would have passed without the photographs being taken. We simply know that the general workings of the world are such that, in the scenario with more clouds, the observation is not made.

Claim (B) is much more tricky. Eddington was a pacifist and this plays an important role in narratives concerning the observation of gravitational deflection. However, in order to establish the dependence between Eddington’s pacifism and the observation, we need to consider many issues. For example, we have to consider the following:

(i) Was it really the case that Eddington’s pacifism was the motivation behind his unique attempt to rebuild international relations during and after WW1? One might wonder, for example, whether Eddington’s scientific ambitions were so strong that, even in the absence of pacifism, he would have seized the moment to make a scientific breakthrough. Call this a cynical view. Or one might wonder, to take another example, whether the scientific reasons, in terms of Einstein’s theory and prospects of experimental success, were so strong that they would have led Eddington to make the observation even if he had no interest in international relations. Call this a naïve view.

The credibility of the two views is difficult to assess. For example, the naïve view can be criticized by noting that people with no pacifist motivation did not have an interest in making the observation. However, the naïve view can be defended (perhaps ad hoc) by noting that Eddington knew particularly well Einstein’s theory and the experimental means to test it. In this way, the debate can continue. The debate will rely on historical details and different ideas of how the world works, i.e., principles concerning the target system. The same is true of the cynical view. We can debate how great the scientific incentives were and whether an opportunistic course of action would have been reasonable in the absence of pacifism. Again, we rely on historical details concerning the situation and on principles concerning how human beings act.

The remarkable thing is that there is no conclusive test for our claims about historical details and principles. Not only are our claims underdetermined by evidence but sometimes it is difficult even to tell how they could be, in principle, tested by evidence. Consider the following:

(ii) Is it really the case that, had Eddington not made the observation in 1919, no one else would have made it during the next hundred years? For example, one could argue as follows: Given the significance of Einstein’s theory and given that the experimental means to test it (by observing gravitational deflection) were relatively straightforward, it does not seem plausible that the observation would not have been made at some point. However, one could argue against this claim by noting that the significance of Einstein’s theory was understood through Eddington’s work. Thus, without Eddington’s pacifism and his effort, Einstein’s theory would not have been considered as significant. The obvious objection to this objection is that someone else would have shown the significance of Einstein’s work at some point even in the absence of Eddington. The debate can continue along these lines.

Again, everything depends on historical details and principles. However, there are serious limits to our reasoning. First, how could we, in principle, know the details of a historical situation concerning, let’s say, the 1920s, that are relevant for our scenario? In the actual history, the scientific landscape was already shaped by Eddington’s result. Secondly, how can we, in principle, test principles concerning the uniqueness of individual courses of action in history or the strength of scientific reasons in the development of science? There are ways to approach these issues, I am sure, but they are unlikely to put an end to our debates about how scenarios would develop.

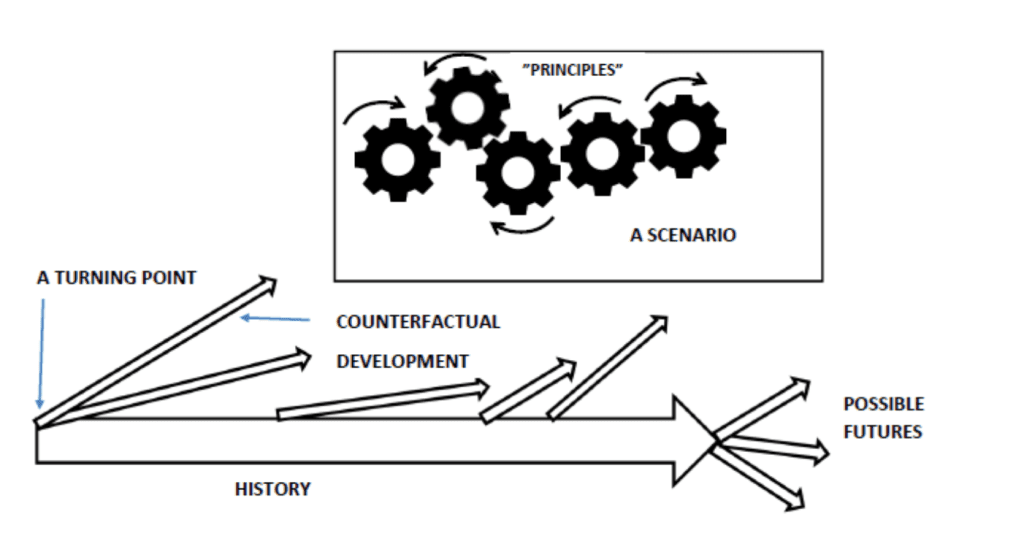

To sum up, we need historical details and principles to track our scenarios. These scenarios track counterfactual developments that attempt to tell what would have happened, had some (presumed) turning point in history been different.

Interestingly, we can build scenarios of the future on the basis of similar considerations related to historical (future) details and principles. In the same way as counterfactual historical scenarios, these scenarios differ in their trackability. To give a toy example, we know that, if the technology in CERN fails, there will be no significant experimental results. On the other hand, we have a much more difficult time if we attempt to tell whether different groups of scientists would make different findings and if so, how and why. In the same way as we attempt to define turning points of the history, we attempt to find turning points of the future. In the case of the future, the potential turning points are our decisions and situations whose nature we are unable to forecast. This means that counterfactual scenarios and historical turning points are an important analogy for our concerns about the future.

The figure sums up the point.

BONUS: How not to criticize a counterfactual scenario

As we noticed, counterfactual scenarios are difficult to track. However, the difficulty is not located where it is sometimes thought to be located. For example, every now and then it is said that even claims like

(A) Had the weather been cloudy, Eddington would not have observed gravitational deflection in 1919.

cannot be tracked. The two standard arguments for the impossibility are the following.

First, if the weather was different, some condition in the past would have been different. This requires an earlier difference and so on, until the dawn of history. Given that the beginning of history was different, we cannot say anything relevant about 1919.

The problem with this argument is that we do not approach our scenarios in this way. Rather, we simply stipulate that the only thing that was different in the scenario was the weather. We are not travelling to a distant world (or discovering them by powerful telescopes, as Kripke said). We construct the initial conditions of the scenario and follow through.

Secondly, had the weather suddenly changed, this change could have had an unexpected impact on the scenario. For example, had the weather suddenly changed, Eddington would have witnessed a miracle. This could have made him pray and thus achieve another miracle, photograph through clouds.

I have called this type of argumentation surrealism-whining (HERE) where every counterfactual claim is doubted because the change in the antecedent requires something out of ordinary (a miracle, an intervention or whatever). It is a ridiculous way of criticizing counterfactual scenarios. To repeat, we simply stipulate the starting conditions of a scenario and follow through. We fix things so that Eddington’s beliefs do not change and no miracles happen. When we discuss the consequence of weather on scientific observation, we are not discussing how crazy the world would be, had there been different weather.

Very proud to be a student at the Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of M’sila.