We currently have two postdoctoral researchers working for the project. Sirkku Ruokkeinen started her research stint in July 2022. In this interview, she tells us more about her contribution to the project and her thoughts on graphic literacies.

How did you first become interested in graphic literacies?

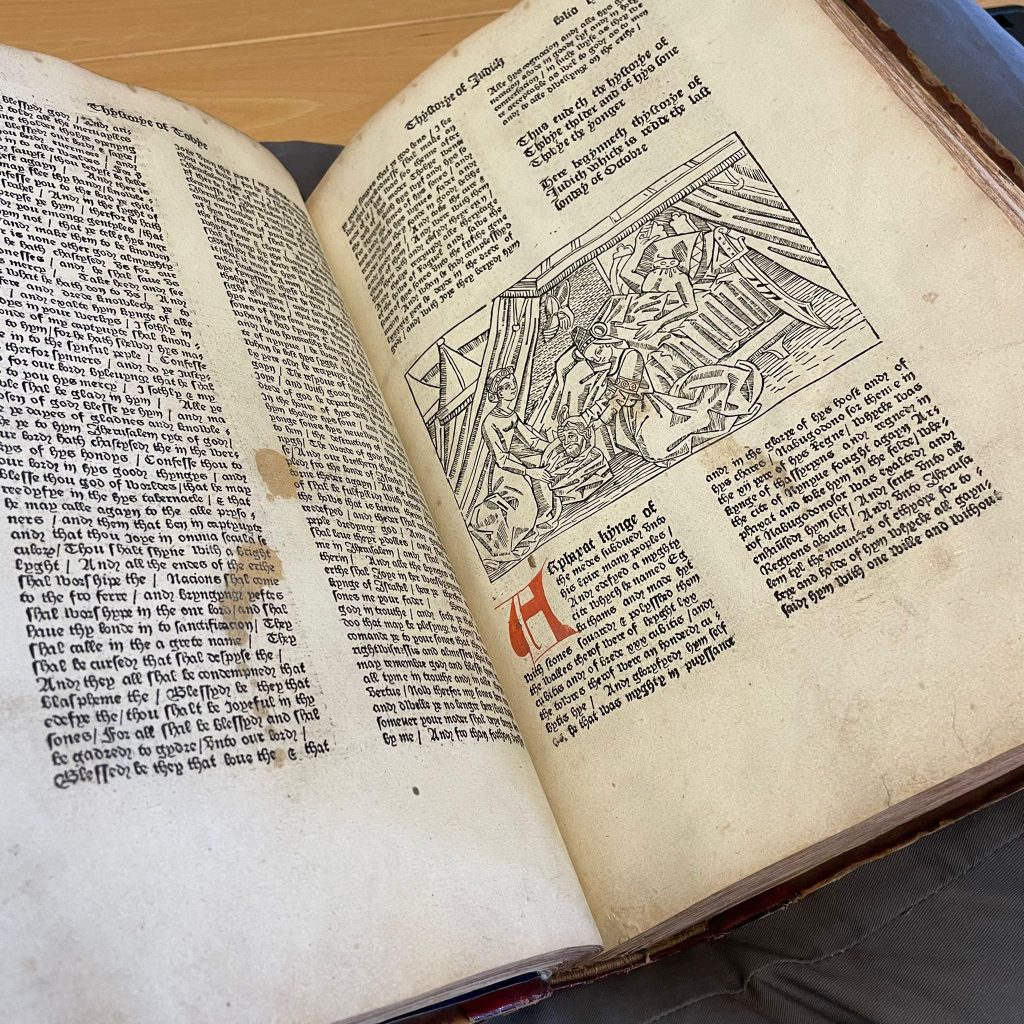

I have always been interested in liminal spaces, especially paratextuality. My interest lies in managing the reader, their expectations, interpretations, and the ways the text is used. The relationship between text and graphic elements is reminiscent of that between text and paratext. What is expected of the reader? What different ways of reading does the author prepare for? How are errors and subversive readings prepared for? How is the reader instructed?

What will be your main area of responsibility in EModGraL?

I will look into how graphic devices are used in paratextual material – whether they were used to promote the work, advance its sales, if the paratextual matter was used to instruct in their use. This analysis will contribute to an overview of the expectations book producers had relating to the graphic literacy levels of the English readership.

What is, in your opinion, the most challenging aspect of the project?

At this stage, given that I have only just worked at the project for a few months, choosing and refining topics of research seems most difficult. There is plenty that could be taken up for study.

Is there a specific domain or genre you look forward to investigating? Why?

I’m especially interested in seeing how the Playfair graphs1 (late 1700’s) and other new graphic elements were framed on title pages and other paratexts, how they were discussed and presented to the audiences. I’m curious to see if there was an expectation of understanding, especially if any of these graphs made it to texts which were intended for non-expert audiences.

Why is studying early graphic literacies important?

It informs us on the ways in which our thinking may have differed from that of late medieval and early modern readers. Models for representing information influence our thinking and understanding of the world.

Sirkku Ruokkeinen & Aino Liira | Twitter: @proemium, @penflourished