1. Introduction

In this post, I discuss how time and temporal scales in the study of the future are intertwined with notions of possibility. I point out that the choice and determination of meaningful temporal scales depend on what is possible and how possibilities can be tracked, and not the other way around. In other words, one should not fix a temporal scale and ask what is possible in that scale. Rather, one should first ask what is possible and to what extent the possibilities can be tracked and only then provide a temporal scale that might fit the possibilities.

I proceed as follows:

First, I briefly introduce different notions of possibility. I discuss such notions as predictable, plausible, possible, alternative, conceivable, and desirable future. Roughly, the notions from predictable to conceivable future can be associated with a widening range of types of futures that are considered.

Second, I discuss why futures studies chooses certain timeframes. I argue that the issues behind the choice carry assumptions about possibilities and how they can be tracked.

Third, I illustrate the problematic way of deriving possibilities from temporal scales by discussing the future cone, which is a well-known hermeneutic tool in futures research. I point out how certain problematic assumptions are carried to that hermeneutic tool.

Fourth, I argue that what is predictable, plausible, desirable, and so on, is highly context-dependent. The context is defined by our epistemic means and the domain of interest.

I conclude by arguing that futures research is a field that studies possibilities and therefore it should not bother so much with fixed temporal scales.

1. Different types of possibilities

In order to understand futures research, it is necessary to have different notions of possibility at hand. In what follows, I identify different notions of possibility and explain what I mean by them and why I think they deserve to be identified. In other words, I provide one way to understand different notions of possibility.

Predictable. By predictable, I mean an event (or a state of affairs or a trend; does not matter here) that follows straightforwardly from the current situation and a set of generalizations that govern the domain at hand and are not expected to change before the event. Moreover, predictability requires that we have epistemic access to the relevant determinants of that future events. We do not have to know the determinants but it must be the case that we would know them if we paid attention to them.

Predictable should not be equated with inevitable or necessary. These are stronger notions. An event can be predictable while not inevitable: to be inevitable, an event must occur even if the initial conditions were different. Predictable events do not need to have this property. It is enough that they follow, given the actual situation.

The notion of predictable deserves to be identified since, arguably, what we can predict is the most clear-cut case of knowledge about the future. Moreover, the ability to say something about the future by following where the current situation leads is a kind of canonical case of future methodology that serves as an exemplar when we construct methodologies of knowing other types of possibilities.

Plausible. By plausible, I mean an event that follows from a credible set of generalizations and a credible description of the current situation. What we consider as credible generalizations and descriptions may not match the reality, but we have good reasons to believe that they are true (or, at least, to be trusted).

Plausible deserves to be identified, as it is the notion that captures the type of knowledge about the future that is not quite certain but credible enough. Plausible captures a reflective attitude toward the future where we believe in certain future events after we have assessed the credibility of the sources of knowledge and admitted their limitations to some extent. This reflective attitude and surrendering to limitations in our knowledge serves as an exemplar to other notions where our confidence towards the knowledge of the future is lower.

Possible. By possible, I mean an event that either (i) is not in contradiction with what we know, or (ii) follows from an internally coherent and somewhat credible set of generalizations and a description of the current situation. Obviously, plausible and predictable events satisfy these criteria and therefore count as possible events. However, possible demands less than plausible or predictable.

Possible deserves to be identified, as it serves as a general category that includes many other notions of possibility. Moreover, possible opens the door to the idea that the future might involve something we do not find credible and, therefore, we need to be prepared for different types of futures and make scenarios of them. Possible serves as an exemplar of other notions that force us to be open to different types of futures.

Alternative. By alternative, I mean an event that goes against what we believe and value. Whereas possible forces us to consider many different futures, alternative makes this a value in itself. An alternative future is a future that follows when we question our knowledge and values and ask “what if we are wrong”.

Alternative deserves to be identified, as it captures fundamental uncertainties in the knowledge of the future and the value-ladenness of our ideas concerning the future. It crystallizes the critical tenets of futures research and the tenets to critically reflect on the conceptions that shape our understanding of the future.

Desirable. By desirable, I mean a future that we find valuable and ethically sound. A desirable future needs to be a possible future, otherwise it becomes an obsolete utopian scenario.

Desirable deserves to be identified, as it explicitly captures the ethical component of futures research. It underlines the fact that we can shape the future and we can shape it for better or worse. Desirable also serves as a contrast to scenarios that follow when we distance ourselves from our current values. Desirable futures underline the fact that the ethical judgments about the future are made by us, different (alternative) futures follow if different values are at play.

Conceivable. By conceivable, I mean an event that is (i) conceptually and ontologically coherent, (ii) and can be known by some means and reasoned about. Conceivable events do not need to be possible events. They do not need to be credible and they can be in contradiction with what we know. Conceivable futures, therefore, include all the futures that can be thought of.

Conceivable deserves to be identified, as it marks the limits of all the possible knowledge about the future. Outside this realm, there are inconceivable futures. These futures we cannot think of or reasons about even though some of them might be objectively possible (see Virmajoki 2022, “Limits of Conceivability”).

We should notice that conceivable events do not include all events that one can form some sort of a mental image. We can imagine all sorts of scenarios that we cannot make sense of in any detail. For example, one might speculate that, in the future, all existing knowledge is proved to be wrong. This might be the case, but we cannot conceive it, as there is no way to reason about what happens in that future: the reasoning would be based on our knowledge which is, by definition, wrong in the scenario. Take another example: One might imagine that we invent a way to turn me into a cat. However, it is not ontologically or conceptually possible that I become a cat; whatever my identity is, it is lost when I turn into a cat.

This points toward the final observation: Not everything that can be asserted and imagined deserves to be understood in terms of the notion of possibility. We should tie the notion of possibility down to methodological steps that can be taken in futures research.

2. Timescales in futures research

Futures research has focused on relatively long timespans, ranging normally from 5-50 years (Nordlund 2012; see also Bauer 2018). However, it is unclear why this is so, or has to be so. The possible answers reflect the history of futures research as well as the goals and nature of the field. First, the historical roots of futures research in national and military planning (Bell 2009, 19; 28-31) probably contributed to the adoption of specific timeframes that were seen as useful in the domains and that thereby shaped the methodological innovations (Bell 2009, 30). Secondly, futures research and futurist have been in the service of clients, and the effect of this is reported by Brier’s (2005, 843) survey. Thirdly, there has been a need for academic identity that separates futures research from mere client-oriented foresight (Brier 2005, 838-840), from those who discuss the near future in media (Brier 2005, 840), and from other fields of research. This final point, concerning the “scientific” identity, is related to the fourth answer: The basic tenet of futures research is to study possible, probable, and desirable futures are studied (Amara 1974; Bell 2009). An essential component in this mapping of futures is the critical study of our own conceptions that different views on the future (Bell 2009; Inayatullah 1998; Inayatullah & Milojevic 2015). Given this, there has to be room for change that could lead to alternative futures. As reported by Brier (2005, 841; see also Bauer 2018), it has been explicitly stated that, in short periods of time, not enough change can happen, and thus the focus on longer timespans. What futures research studies and what thus separates it from other fields suggest a certain timespan related to the notion of future.

While the long timescale is justified in futures research, it would be unfortunate to conclude that futures research is nothing more than the study of what could and should happen in a long timescale. This is not the case. Not everything that says things about possible futures is futures research even if the timescale is shared. Rather, futures research focuses on processes and factors that potentially shape the future and on the methodology that tracks these processes and factors. It is far from obvious that focusing on events, processes, and patterns over a long time span is the only way to investigate how humans live in time and interact with reality through time.

In order to see how futures research is connected to what we wish to know, it is insightful to start from the opposite direction and see why futures research does not usually engage with very long timeframes that go beyond 50 years or so. In Brier (2005; see Bauer 2018 for similar insight), the following reasons are given. First, the longer timescales are beyond the needs of clients. Second, people cannot relate to futures further away. Third, forecasting becomes more difficult with longer timescales for many reasons. Fourth, the further we go, the more the futures sound like science fiction to audiences. Fifth, accounts of the future affect the future, and the longer the timescale, the more intertwined these two become. Three of these issues hit the scientific core of futures research: difficulties in estimating the future, the entanglement of the future with accounts of it, and the (in)ability to relate to certain futures.

First, difficulties in telling the future have been extensively discussed in futures research. Many reasons for these difficulties have been given. They range from metaphysical to methodological to conceptual. For example, Bell argues, following Amara (1981), that the future is open: “The future is a domain of liberty not simply because we cannot know the future in any certain sense. It is also because the future itself is contingent, not only of our knowing of it” (2009, 151). Methodological reasons are discussed, for example, by Gordon (1992). He concludes “Do the methods work? Certainly, under limited conditions and for limited intervals. Will they ever be perfect? Not as long as chance plays a role in determining the future and people can decide to take action” (1992, 35). Conceptual reasons are discussed, for example, by [omitted for review] who argues that interesting futures can be beyond what can be conceived.

Secondly, that accounts of the future affect the future through human behavior has been pointed out already by Popper (1957, 13) and has been taken pretty much for granted. This entanglement is even built into the core of futures research when the field is related to the purposes of emancipation and planning (see Bell 1997; Marien 2002). Surely, there has been also a focus on unexpected and unintended consequences (e.g., McDermott 1993) but this focus is logical only if expected and intended consequences serve as the contrast.

Thirdly, people´s ability to relate to certain futures is studied when (i) desirable futures are studied, and also (ii) when the participation of different groups in futures research is discussed (Bell 1997, 93-95). For example, Sand discusses different senses in which people might “not have a future” and argues that we should be “aware that there are numerous people, who neither entertain their own vision of a desirable socio-technical future [–], nor do they have the means to strategically position them in the discourse and, thereby, contribute to their realization” (2019, 99). The (in)ability of people to work towards a future and find a future relatable, desirable, and familiar are issues that futures research studies.

To sum up, we can see that there are several issues at the core of the futures research that are intertwined with temporal scales: epistemological difficulties, our prospects of affecting the future, and ethical considerations. As Bauer notices, “Time horizons are strongly linked to the possibility and methodology of knowing the future” (2018, 40).

Interestingly, these issues are connected to the different types of possibility that are relevant in futures research:

1. The notions of predictable, plausible, probable, and alternative are intimately related to epistemology and critical reflection on sources and credibility of knowledge. For example, plausible future events are the type of events that we can infer from the knowledge we find credible, and alternative futures are futures that can be inferred once we distance ourselves from our current knowledge.

2. That accounts of the future affect the future is also built in the notions. All of the notions are at least compatible with the idea the future happens through human agency. We can also understand the decrease in confidence from predictable to alternative in terms of increasing uncertainty that is introduced by human choices. However, the idea that accounts of the future affect the future is most visible in the notions of desirable and alternative. Desirable acknowledges that there are future possibilities that we should seek. Alternative acknowledges that different conceptions of a domain of life lead to different future scenarios and, therefore, we should critically assess how our actions toward the future are shaped by our conceptions of it.

3. Differences in the ability to relate to certain futures are related to different notions of possibility. The more confident we are about a future, the more we expect it to happen. Given the expectation, we can prepare for the future and, therefore, we can more easily find the future relatable. Moreover, desirable futures are the types of futures that we are comfortable with, ethically speaking. Alternative futures are the types of futures that we can make scenarios of by critically distancing ourselves from our knowledge and values and this means that our ability to relate to the alternative futures is diminished. They are futures that go against what we expect and value.

Given that (i) at the core of the futures research are epistemic difficulties and challenges in knowing the future, the entanglement of the future with accounts of it, and the (in)ability to relate to certain futures, and (ii) these core issues are connected to the notions of possibility, it follows that the study of the core issues is a study of possibilities, and vice versa. Next, I will argue that different notions of possibility cannot be mapped with temporal scales in any straightforward manner. If I am correct in this, it follows the core issues (i.e., epistemic difficulties and challenges, the entanglement of the future with accounts of it, and the (in)ability to relate to certain futures) are not associated with temporal scales in any straightforward manner. This is due to the fact that the core issues are associated with different notions of possibility and these notions cannot be mapped with temporal scales in any straightforward manner. Temporal scales do not determine what can and cannot be said about the future.

3. The Problematic Association of Temporal Scales with Possibility

In §2 above, we saw some reasoning behind the choice of temporal scales (usually 5–50 years) in futures research. The idea behind such scales is that, on the one hand, there are limits in epistemology and motivation for longer scales, but, on the other hand, the types of changes that futures research are interested in require time and, therefore, futures research is motivated by considerations that do not relate to most immediate futures. However, it is far from obvious that the intuitive connection between timescales and knowledge and change holds under closer scrutiny.

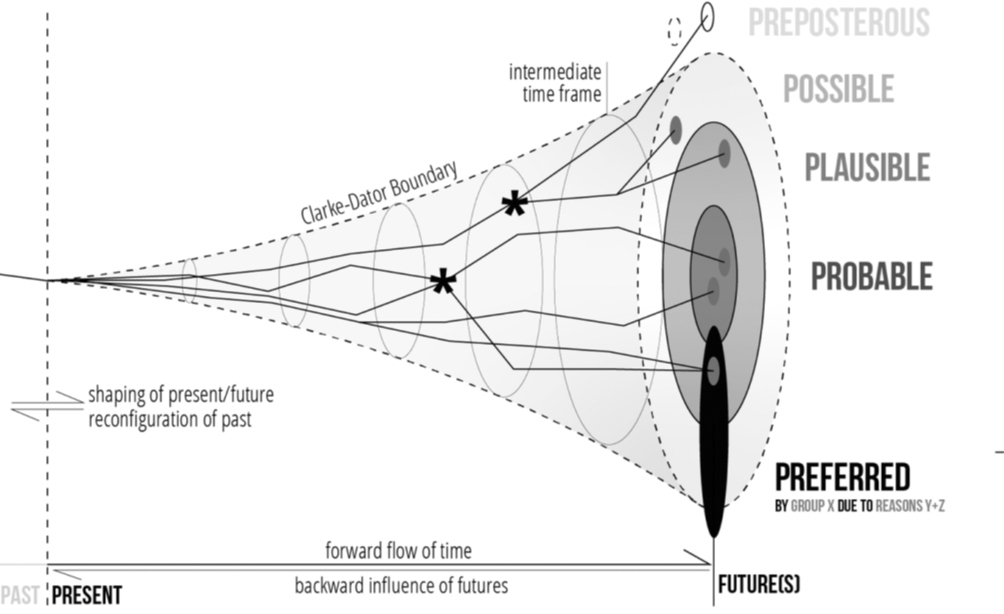

Consider the so-called future cone. It is a hermeneutical tool that is used to understand the connections between the flow of time and different types of possibility. Below, there is a cone that has been taken from the recent paper “How to visualise futures studies concepts: Revision of the futures cone” by Gall, Vallet & Yannou” (Futures 143, 2022).

It is interesting to notice that the cone presents the types of possibilities as something that co-exist with each other at any moment of time. Moreover, it presents “an ever-expanding possibility space” (ibid.), the idea being that the further we go in time, the wider the space of “objective possibilities” is. Both these assumptions are problematic.

First, rather than maintaining their relative portion of the space of possibilities, predictable (or probable), plausible, probable, desirable, alternative, and conceivable futures should be seen as shrinking in size the further we go. For example, inaccuracies in our description of the current situation and generalization and the influence of external factors make it very hard to predict anything (or judge as probable) in long timescales. The same is true of plausible. The further we go in time, the more difficult it is to produce scenarios of the future that are based on credible assumptions.

That desirable (or preferable) and alternative futures shrink into nothingness is less obvious but still true. For example, given that the desirability of a future depends on values and matters of fact that are relevant to the values, the desirability of a future can be decided only if we can track meaningful changes in the values and in the relevant matters of fact. The tracking requires that we can form plausible scenarios. Given that plausible futures are more and more difficult to identify the further we go, desirable futures are equally difficult to identify. Moreover, alternative futures are futures that follow when we question our conceptions that we use to understand the future. Given this, alternative futures can be identified only against futures that are consistent with how we understand the world. Given that our ability to track futures that are in harmony with our understanding shrinks as we move forwards in time, the number of futures that can serve as a contrast to alternative futures shrinks and, therefore, alternative futures shrink.

This means that different areas in the future cone should become non-existent as we move forwards in time, and they should become non-existent at different points of the cone. This also means that the timescale that we can use in analyzing the future depends on what type of possibility we are satisfied with. If we wish to have plausible futures, we cannot go too far away; if we are satisfied with conceivable futures, then we can move much further than centuries forward. What we cannot do is take some moment in the future and ask which futures at that moment are predictable, plausible, alternative, and so on, because these types of possibilities might not exist at that moment. The futures cone is fatally misleading in this issue.

Secondly, the idea of expanding space of possibilities does not seem obviously correct. There probably are limits to what is possible and what is not. In order to tell whether the number of possibilities can increase in time, we need to understand what is possible in the first place. Moreover, the expanding space of possibilities seems to carry a naïve assumption about human development and choices: the further we go in time, the more we are capable of doing and more things become possible. However, given the fundamental challenges we face, such as climate change and nuclear weapons, it might very well be the case that all paths toward the future lead to a catastrophe in the coming decades or centuries. Such a catastrophe would shrink the cone into a rather small line.

The important thing to notice here is that the difficulties and challenges in describing predictable, plausible, possible (and so on) futures cannot be derived from the supposed fact that the space of possibilities is expanding. We cannot tell whether there are more possibilities as we move further in time without studying what is predictable, plausible, possible, and so on. We should not be held as prisoners by our intuition that possibilities multiply as we move forward in time.

To sum up, it is misleading to think that different types of possibilities exist at any moment in the future, and it is equally misleading to think that temporal distance is a determinant for the size of the space of possibilities. Given that we shake off these misunderstandings, it is possible to think about the relationship between timeframes and possibilities in different ways.

First, one can first choose the type of possibility one is satisfied with and then study which futures are possible in the chosen sense of “possible”. Once the futures are mapped, one can give an estimate of the timescales in which the futures could take place. For example, I might choose to focus on plausible futures and then study which futures of particle physics are plausible. I could judge, for example, that it is plausible that a new particle collider will be built. I could then estimate that this takes some decades to be realized and, after that, I have no access to what can plausibly happen.

Secondly, one can first a timeframe and then study different scenarios in that timeframe. One could then study whether different scenarios are plausible, possible, and so on. However, one might find that, given the choice of timeframe, no scenarios are plausible or possible, and so on. Possible disappointments lurk in this type of approach. For example, I might study what could happen in particle physics in the next 50 years and conclude that I have no plausible or even possible scenario of how things will be in 50 years, given the possible turmoil in the field.

Thirdly, one could choose different types of possibilities as the focus and then study how different scenarios fall under different types of possibilities (i.e., whether a scenario is plausible or conceivable, and so on). After that, one could map different temporal scales with different scenarios. An interesting outcome that can arise in this type of research is that the temporal distance of a scenario from the current moment may not correlate with the type of possibility that the scenario falls under. For example, some plausible scenarios could be further away in time than some merely conceivable scenarios. I turn to this issue next.

4. The Horizons of Possibilities

Given the many types of possibilities that futures research focuses on, it can be argued that futures research is more about possibilities than it is about the future itself. As we have seen above, the three tasks of (i) formulating scenarios, (ii) analyzing in what sense the scenarios are possible, and (iii) associating a temporal scale with a scenario are separate from each other and can be prioritized differently.

Next, I wish to point out that the types of possibilities are more disconnected from temporal scales that have usually been understood in futures research. Moreover, I show how temporal scales and knowledge of possibilities are context-dependent in that they depend on what domain of life we focus on and what considerations we use in order to track that domain. In order to show this, I wish to go through a somewhat lengthy illustration. Considered the case that I have used before (see https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13194-023-00510-3 for details). As an exercise, let us create scenarios of the future of science in terms of Kuhn’s theory of scientific development:

In Kuhn’s philosophy of science, there are (mainly) two kinds of periods in the development of science: normal science and revolutionary science. A normal science period is a one in which a paradigm defines the research in a scientific field. A paradigm is a “universally recognized scientific achievement that for a time provides model problems and solutions to a community of practitioners” (Kuhn 1970, viii). A paradigm, then, is the condition under which science can develop in a steady fashion. Revolutionary science, on the other hand, is a period in which an existing paradigm is challenged due to its inability to solve important problems and a new paradigm is establishe”. Different paradigms are mutually incommensurable, as there are no shared standards that enable scientists to choose between competing paradigms in the period of revolutionary science. Kuhn makes the point dramatically: “the proponents of competing paradigms practice their trades in different worlds” (1970, 150). It is understandable, then, why a change of paradigm constitutes a scientific revolution.

Kuhn’s account defines a possible structure of the future of science. If Kuhn is right, whatever the details, science will be dominated by a paradigm and this domination will end during a revolution. Given this structure, we need to fill in the contents in order to create scenarios. Which paradigms will continue their dominance? Which paradigms are under serious doubt? What are the possible courses of action, given that a field of research is facing a crisis?

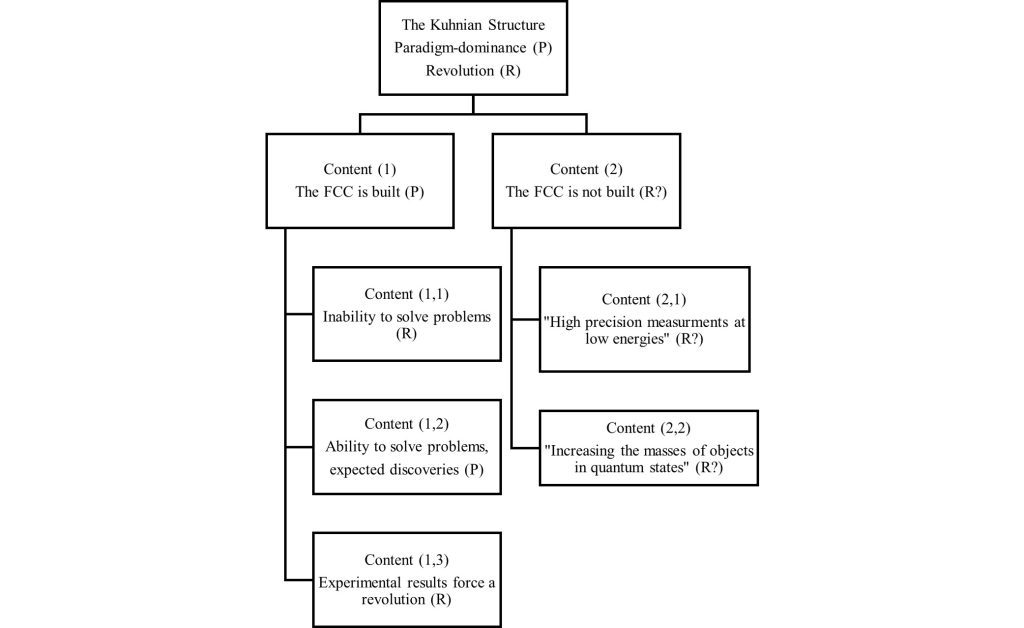

As an illustration (see the figure), consider the debates concerning the Future Circular Collider (FCC). The debate concerns the possible discoveries and new knowledge created by the FCC. Sabine Hossenfelder (2020) has argued that the cost of the FCC is too great given the chances of possible discoveries. Michela Massimi (2020) has argued that the FCC can be defended once we understand scientific progress not in terms of “great” discoveries but in terms of excluding possibilities. This debate provides us with two main branches of scenarios. The first branch concerns whether the FCC is built. The second branch concerns the possible futures in the situation where FCC is built.

Take the first branch. Given the Kuhnian picture, either the paradigm set by the research with the Large Hadron Collider will continue as the FCC is built (contents 1), or the uncertainty about its ability to solve important problems leads to a decision to attempt some other approaches in physics (contents 2). Hossenfelder gives two examples of such alternatives “high precision measurements at low energies or increasing the masses of objects in quantum states” (2020, paragraph 11). Notice that in the Kuhnian structure, there is an ambiguity about whether the contents (2) count as revolutionary. On the one hand, contents (2) would be the outcome of the inability to solve central issues within high-energy physics. On the other hand, Hossenfelder’s suggestions stem from the current background of physics. As Toulmin (1970) pointed out, the absolute revolution vs. normal science distinction is a too restrictive interpretive tool.

Next, take the second branch. Hossenfelder argues that it is possible that no significant discoveries will be made with the FCC (content 1,1). In the Kuhnian structure, the inability to solve problems leads to a revolution. Massimi argues that, in addition to clear discoveries that are to be expected on the basis of current theories and methodology (content 1,2), it is possible that “vain” experimental attempts create the ground for “a revolution similar to the one behind relativity theory in rethinking the theoretical foundations for a new physics” (2020, paragraph 13) and such revolution in the foundations of the Standard Model is one possible content (content 1,3).

Figure 1. presents a taxonomy that is created by adapting a Kuhnian structure and the examples of contents taken from Hossenfelder and Massimi. Each node (1)—(2.2) presents a scenario of a possible future of science. The taxonomy shows how the Kuhnian structure classifies different futures with respect to their place in the paradigm-revolution scheme. The structure adds a level of interpretation of the future possibilities as it enables us “to discern the possible states toward which the future might be ‘attracted’” (Staley 2002, 78).

There are several observations that we can make:

First, there is already a discrepancy between the plausibility and timescale of contents (1) and (2). While it is arguably more plausible that the FCC will be built rather than not, the temporal distance to the FCC is several decades. On the other hand, a movement to other methods and techniques that could be used in the absence of the FCC (i.e., if it is decided that the FCC is not built) could begin at any moment, given that the plans for FCC are abandoned. Here, the plausible scenario is further in the future than a mere possible scenario.

Secondly, we can see that it is impossible to say which of the five scenarios (1.1)–(2.2) is plausible in a long run. They all seem possible (or at least conceivable). This is due to the fact that, in the case of science, we have serious difficulties in telling where the current situation could lead us. In order to say that a future is plausible, we need to use our current knowledge. However, the whole point of estimating the futures of science is that our current knowledge might turn out to be defective. While we could say that scenario (1.2) is what we expect on the basis of our current theories, it would be arrogant to accept it as the plausible scenario. The whole point of developing the methodology of physics further is to study whether our theories are, in fact, correct. In the case of the FCC, the heuristic tool of the future cone is misleading. At a certain point in time, the number of plausible futures shrinks to nothingness.

Moreover, one could also add that it is impossible to say which of the scenarios (1.1)–(2.2) are desirable. On the one hand, there is the temptation to say that all of the scenarios are desirable, as science develops wherever it wishes. On the other hand, it seems that the proponents of different approaches have clear preferences for the future and, therefore, the idea that every scenario is desirable seem inconsistent and unpractical. If every scenario was desirable, we would not have the motivation to drive towards any of the solutions and we would achieve none of them.

Thirdly, there are scenarios that suggest that a similar outcome is possible but disagree on the timescale of the outcome to a great extent. For example, contents (1,1) and (1,3) both constitute a scenario of revolution, but they disagree on when a revolution is possible. Content (1,1) suggests that a mere lack of results leads to a revolution, whereas (1,3) suggests that revolution requires that there are further experimental results that do not fit the existing theories. Content (1,1) sets the time for a revolution at the moment when we get frustrated. Content (1.3) suggests a timescale of many decades for the revolution by following Massimi’s analogy “the road to Einstein’s breakthrough meandered through half-century-long attempts at engineering models of the ether and testing for the ether”. This means that one future outcome can be judged possible through several considerations but the timescale associated with the future depends heavily on the nature of the consideration that leads us to the future. For example, content (1.3.) suggests that there is no possible future of revolution within the close future. This shows that, while plausibility and possibility often shrink as we move forwards in time, sometimes plausible and future only become existent after a certain period of time.

To sum up, we can see that it is one thing to create scenarios and it is another thing to associate them with types of possibilities and temporal scales. Moreover, the illustration shows how temporal scales that we associate with different scenarios and their type of possibility depend on the domain of life and our epistemic means to study that domain. In our illustration, we see how the nature of science shapes what kind of future possibilities we can discern. The temporal scales that are relevant in big science are measured in decades. Moreover, the nature of science has the consequence that we have unique difficulties in telling what futures are plausible: plausible futures are determined through our current knowledge, and the changes in science are changes in that knowledge. Therefore, we need to be more cautious about what knowledge we can use in judging the plausible futures in the case of science.

5. Conclusion

In this post, I have identified different types of possibilities that futures research can focus on and argued that they have no straightforward mapping to temporal scales of different lengths. Given that in the scientific core of futures research are the issues of (i) epistemic difficulties and challenges in knowing the future, (ii) the entanglement of the future with accounts of it, and (iii) the (in)ability to relate to certain futures), we can notice that what futures research can do and achieve is not determined by certain temporal scales. Let me explain.

First, epistemic difficulties and challenges depend on the methodology available and on the domain of life we are interested in. The difficulties and challenges are not difficulties and challenges in knowing what can happen at a certain timespan. Rather, they are difficulties in knowing possibilities and the type of possibility that a scenario falls under. Our epistemic difficulties and challenges do not increase or decrease (or change their form) in relation to time but in relation to the domain of life and our ways of dealing with possibilities in that domain.

Secondly, the fact that the future is entangled with our accounts of it has a connection to different types of possibilities. For example, consider the notions of plausible and alternative futures. Plausible futures are futures that are the outcome of what we count as credible developments. Given this, we can understand the construction of a future in terms of how we plan for it on the basis of our judgment of plausibility. Moreover, alternative futures are futures that arise when we abandon the beliefs we usually take for granted. Given this, alternative futures are constructed (if they are constructed) on the basis of challenging what is been taken for granted. In both cases, the entanglement of the future with the accounts of it does not increase or decrease in relation to time but in relation to our judgments of possibilities and the way we operate our modal beliefs.

Thirdly, whether we find a future relatable or desirable depends on whether is in accordance with our values and whether we can understand how that future came into existence. For example, even if a revolution in science was a somewhat desirable outcome, the fact that it follows from mere frustration might make a future with a revolution unrelatable. What limits our ability to relate to a future is not its temporal location but how it is connected to our beliefs about possibilities and how they can, and should, be realized. Given that our ability to know possibilities is not related directly to temporal scales, neither is our ability to find a future desirable and relatable.

All in all, we can see that futures research is not about what can happen at some temporal scale. Rather, futures research is about possibilities. To what extent we can map different types of possibilities depend on our epistemic means and the domain of life that we are interested in. It is unfortunate that futures research has built so much of identity on temporal scales.

Time, possibilities, and future knowledge do not relate to each other in the way that naïve hermeneutic tools such as the future cone suggest.

References

Amara, R. (1974), “The Futures Field: Functions, Forms, and Critical Issues”. Futures 6 (4). 289-301.

Bell, W. (2009). Foundations of Futures Studies. Part 1.

Brier, D. (2005). Marking the future: a review of time horizons. Futures

Gordon, T. (1992). The Methods of Futures Research. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science

Hossenfelder, Sabine (2020). “The World Doesn’t Need a New Gigantic Particle Collider”. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-world-doesnt-need-a-new-gigantic-particle-collider/.

Inayatullah, S. (1998). Causal layered analysis. Poststructuralism as method. Futures

Inayatullah, S. (2008). Six pillars: futures thinking for transforming. Foresight

Inayatullah, S. and Milojevic, I. (Eds.) (2015). CLA 2.0.

Kuhn, Thomas S. (1970). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions [2nd ed.]. The University of Chicago Press.

Massimi, Michela 2020. “More than prediction”. Frankfurter Allgemeine. https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wissen/physik-mehr/planned-particle-accelerator-fcc-more-than-prediction-16015627.html

Nordlund, G. (2012). Time-scales in futures research and forecasting. Futures

Sand, M. (2019). On “not having a future”. Futures 107. 98-106.

Staley, David J. (2002). “A History of the Future”. History and Theory 41 (4). 72-89.

Toulmin, S., 1970 “Does the distinction between normal and revolutionary science hold water?”, in Lakatos and Musgrave (eds.) Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge. 39–5.