Johanna Niemi

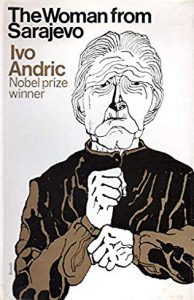

The Woman from Sarajevo (Gospodjića, 1945), a novel by the 1961 Nobel laureate Ivo Andrić, starts with a lonely death, first suspected as a murder. The deceased turns out to be a usurer who has just met her lonely end. The teaching of the novel is that greed leads to misery. Thus, Andrić joins the literary tradition of Shakespeare (The Merchant of Venice), Dostoyevsky (Crime and Punishment) and Dickens in depicting the usurer as a greedy, morally despicable creature. Interestingly, Shakespeare wrote well before the industrial revolution, while Dickens and Dostoyevsky more or less coincide with it and Andrić’s novel tells about the time around the First World War, a time when the role of credit was quickly expanding.

The world literature does not explain what usury is. There is a strong historical sentiment in Christianity and still existing in Islam that all money lending for interest is morally reprehensible, if not outright forbidden. According to this line of thinking all money lending would be usury – a standpoint that would be untenable in an industrial market economy. Nor do the great writers suggest that all money lending would be usury, just the particularly heinous and greedy practices. In the contemporary credit society credit given by greedy individuals plays a rather marginal role, nor does it appear to be popular theme in contemporary fiction.

In credit societies, credit is generally available from institutional sources. Increasingly it is cross-border. For example, the newspapers reported just before Christmas that already fourth Norwegian internet bank starts to offer consumer credit in Finland. Typically the credits are between one thousand and 50.000 euros, with an interest of 20-50 per cent for loans below € 10.000 and between 12-20 per cent for loans below that amount. On special offer are consolidating loans to pay off several outstanding consumer credits. There is no discussion about whether these interest rates are reasonable. Rather, the Finnish government is worried because Finland has no positive credit register and has commissioned a study whether such a register would be desirable.

Reading news like this those of us whose interest in consumer credit derives from work with over-indebted debtors and households wonder what kind of debtors are willing to agree to these kinds of interest when the market rate for many credit forms has for a long time been very low, even close to zero.

Image by Jörg Hertle from Pixabay

Luckily, Udo Reifner has given us the necessary tools to contemplate about this. If you have not yet read the book Usury Laws by Udo and Michael Schröder (2012), I recommend to do so. The book has the most boring subtitle of an EU project: ‘A legal and economic Evaluation of Interest Rate Restrictions in the European Union’ but it is dynamite.

It turns out that the European countries have a strong tradition and sentiment against usury, both historically and in present time. However, what practical conclusion should be drawn from that sentiment seem to be lost in the contemporary credit economy. There is no common European policy or law, but the member states have set up their own policies, which vary widely.

Actually, usury may just be a catchy title for the more boring regulation: Interest Rate Restrictions (IRR). Interest Rate Restriction, however, indicates that there should be some legally set rate to the highest acceptable interest level but that is not the case, nor do the authors propose that there should be one. Usury as a term suggests that there is some kind of limit to what is acceptable in individual cases. And that seems to be the opinion of most legislators.

So, what is usury and why the concept has been marginalized in credit societies? Looking at examples from fiction, the answer is clear: Usury refers to situations of individual exploitation in which the usurer knows the vulnerabilities of the exploited person. In a credit society this is rarely the case.

Based on the information compiled in Usury Laws, regulation of usury can be systematized into three types: the civil law tradition, the criminal law and the administrative/consumer protection regulation. These three disciplines of law approach usury in different ways and with different sanctions. This is interesting in itself, and a further study should evaluate how the choices between different legislative strategies have been made and how these choices affect the credit market and the debt problems. Here I just want to summarize some of the findings of Udo’s and Michael’s study.

In the following summary I proceed with the degree of individualization vs. general standard setting by the regulation. I start with criminal law, which is most focused on the individual liability, proceed to civil law and finally to administrative/consumer protection law, which is market regulation by nature. My analysis is illustrated in a table below.

The allocation of criminal liability is based on individual culpa. There is no crime nor punishment without a basis in the law, nulla poena sine lege. This principle requires that the elements of a crime are precisely enough defined in law. In addition, to be held liable the accused person must have known about the factual criminal elements, such as the vulnerability of the victim, and s/he must have had the criminal intent. Thus, the criminal law is suited for situations in which the creditor has detailed knowledge about an individual debtor and her circumstances, not for anonymous market transactions.

The criminal law is mostly oriented towards the natural persons. However, there is increasing discussion about the criminal liability of corporations in criminal law. Some jurisdictions do have a criminal fine on a corporation, a sanction that could be efficient in usury type of actions by corporations.

The criminal sanctions do not address the problems of unbalanced credit transactions. The criminal sanctions, typically fines, prison sentence and community service with or without rehabilitative aspect, do not modify the credit transaction per se. A civil law remedy, such as compensation or damage payment or annulment of a contract, can be adjudicated in the criminal procedure but the procedure does not necessarily favor an individually adapted remedy.

In civil law usury can be prohibited in the form of a prohibition against extortionate contract stipulations and in particular against the exploitation of the vulnerable situation of another person. Such a prohibition may require that the creditor knew about the vulnerable situation of the debtor.

Image by mohamed Hassan from Pixabay

The civil law remedies are designed for contractual relations and allow for annulment or adjustment of a contract or a specific part of the contract, such as interest. However, only some jurisdictions have explicit legal provisions that regulate how an extortionate interest clause affects the validity of the contract, ranging from the annulment of the whole contract to total and partial disregard of the obligation to pay interest.

Reifner and Schröder see a shift from this kind of morally based regulation of contracts towards a market evaluation model, in which the evaluation of the contracted interest is done against the market rate of interest. Historically, this type of regulation has been more common in Romance countries than in continental countries. The reference to market rate has been formulated, for example, so that an interested above double the market rate has been forbidden. There is no universal norm in contemporary Europe, but Reifner and Schröder found several examples of market based standards of interest rate restrictions, connected to different market rates with varying percentages. There seems to be no common policy when the rate ceilings vary from some six percentage to over four hundred (that is four time the capital of the loan). The regulations also vary according to the type of credit.

Finally, an administrative setting of interest rate restriction comes close to civil law regulation but the focus is on regulating the whole market instead of individual contracts. Substantially the difference to civil law approach is not necessarily big, but the institutional and procedural settings are different.

In traditional contract law the evaluation of the acceptable interest rate ceiling is set up by courts in individual cases. In consumer protection approach an administrative body or a central bank regulates the interest rates. Thus, information about a defined highest interest rate(s) is publicly available.

In addition, the supervision of the system is tasked to institutions that specialize in consumer protection or market regulation. Such an institution may take action either on its own initiative or on the basis of complaints. The concept of sanctions is related to market behavior and can include loss of license, prohibition to use an illegal standard contract clause foe example.

Table. Three traditions of usury regulation.

| Regulation | Rationale | Creditor | Debtor | Sanction |

| Criminal Code | Prevent exploitation | Individual, culpa | Individual vulnerability | Penal sanctions |

| Civil Code | Good morals; market | Individual, bad faith | Individual, weak | Contract or interest is void, total or partly |

| Administrative/ Consumer law | Protect consumers, standard contracts | Institution | Consumers as (a) group | Loss of licence; prohibition of clause |

The economic part of the book, analyzing the impact of interest rate restrictions is written by Michael Schröder. A very rough summary of this analysis is that overall impact on the credit market is not that big since usury ceiling is well above normal competitive market rates. However, there may be an impact on the position of vulnerable groups of debtors and on certain credit forms. The interest rate restrictions may exclude high risk debtors from access to credit. The interesting question from the perspective of over-indebted debtors and households is, do caps on interests reduce or increase the risk of over-indebtedness. There is no conclusive evidence to answer this point, however.

With Reifner and Schröder’s book we are much better equipped to contemplate on usury, acceptable interest rates and the impact of regulating them. The book should be compulsory reading to all law drafters, students of contract and market law, researchers on debt problems and comparative law scholars. So, basically to everyone.

Johanna Niemi is Minna Canth Academy professor and professor of procedural law at University of Turku