Our EModGraL team and other philologists at the Turku Department of English will be strongly represented at the ICEHL this year. The 22nd International Conference on English Historical Linguistics takes place at the University of Sheffield, 3 – 6 July 2023. Below we will give a brief overview of our papers to be delivered at the conference. For the full abstracts, see the book of abstracts published on the conference website.

EModGraL research

The conference programme includes three papers discussing research done as part of the EModGraL project.

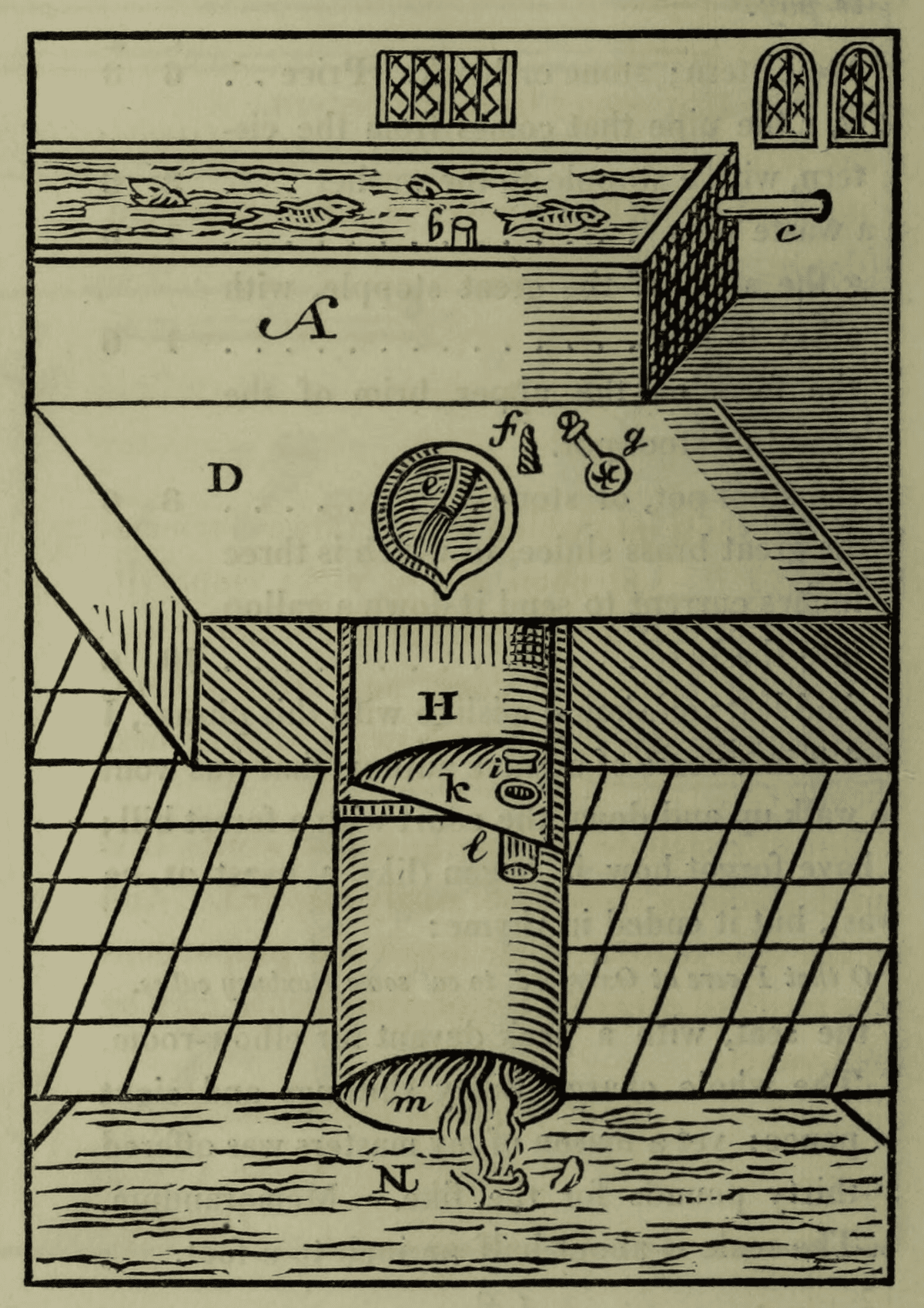

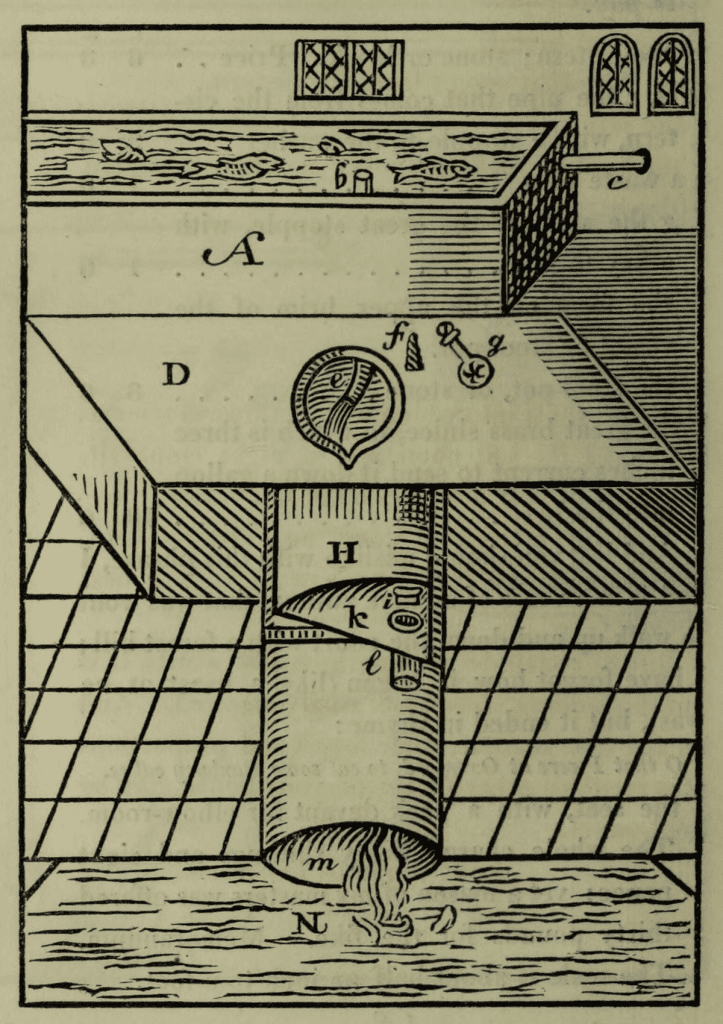

Vice-PI Mari-Liisa Varila will give a paper entitled ‘Captions and caption-like elements related to graphic devices in early modern English medical texts’. She analyses the relationship of the text and the graphic devices and identifies the different purposes that captions and caption-like elements served in medical texts, such as identifying the device or providing the reader with instructions.

The paper by Aino Liira and Wendy Scase (University of Birmingham) will focus on various table-like elements and the vocabulary surrounding them (title: ‘Tables, lists, rules and accounts: Tabular “graphic devices” in Early Modern English books’). In this paper, they take a closer look at items which have been tentatively placed under the category of ‘unclear tables’ in the EModGraL data collection process, and aim to find out how such graphic items were conceptualised by early modern authors and book producers.

Sirkku Ruokkeinen’s paper ‘“With diuers Tables annexed for the present making of your battells”: Paratextual framing of graphic devices in sixteenth-century military works printed in England’ discusses the use and framing of graphic devices in sixteenth-century works addressing military strategy and education. She particularly focuses on the title-pages and paratextual front matter of the books, where the graphic devices were advertised and discussed in order to promote the work.

Other research

The EModGraL team members and our colleagues at the English department are involved in several interesting research projects, and we decided to take the opportunity to introduce these as well.

Hanna Salmi will give a paper closely related to the EModGraL research interests. The title is ‘“I think my self obliged to place three Figures here together”: Framing graphic elements in 18th to 19th century dance manuals’. In this paper, she draws into focus an under-researched genre of dance manuals, which featured many kinds of graphic devices and visual notation. To shed light on the use of these graphic elements which supported verbal dance instructions, she examines how they were framed and explained to the reader.

Scribal practices are discussed in a joint paper by Peter Grund (Yale University) and Matti Peikola, entitled ‘Colonial orthographies: Uses of the ampersand in the legal documents from the Salem witch trials’. Their research reveals that there were clear differences in how the recorders at the Salem witch trials (1692–3) used the ampersand and the Tironian et (⁊), as opposed to the written-out and. They also show that several linguistic and extralinguistic factors played into this variation. Their paper is part of a broader project on the orthographic features of the witch trial documents.

Sara Pons-Sanz (University of Cardiff) and Janne Skaffari’s joint presentation ‘Orrm’s French- and Norse-Derived Terms’ is part of a workshop focusing on the Ormulum, a sermon collection from the late 12th century. In this paper, Janne looks at the French-derived words, many of which represent the lexical field of faith.

The research project ‘Between Science and Magic’ (@titaraproject; PI Mari-Liisa Varila) is represented at the conference by Ida Meerto, who presents some results of her PhD study in a paper entitled ‘Genre and Subject Matter in the Use of Words for Witches in Old English Prose’. She focuses on a selection of the most commonly occurring words, discussing how the word choice depends on the genre or register of the text but also on the temporal and geographical setting of the narrative.

We’re looking forward to an invigorating conference experience and many interesting discussions on the history of the English language!

Text: Aino Liira & the authors named

Photo: Johanna Rastas