The first-year mark of EModGraL is fast approaching. Dr Mari-Liisa Varila, the Vice-PI of the project, has recently completed her postdoctoral research stint. We interviewed her about her past and future work for the EModGraL project.

Dr Varila, your research stint in the project has recently come to an end. What have been some of your main tasks or responsibilities in EModGraL?

I participated in designing the EModGraL data collection procedure, and I collected data from incunabula and 16th-century books. Much of my time was spent on research and writing, but I also taught a three-session MA module on the project theme. I’m also the vice-PI of EModGraL and lead the work package focusing specifically on medical texts.

Your work as the vice-PI of the project continues and a part of your working hours as lecturer will be devoted to the project. What are some of the things that you will continue to work on?

I’ll continue to work on the medical texts work package. This autumn I’ll be focusing on an article on graphic devices in printed medical texts in 1500–1700, co-authored with our collaborators Jukka Tyrkkö and Carla Suhr. I’ll also continue to work on some other aspects of the project, as well as publications, including an edited volume and an article on our project methodology.

What has been most exciting about the project?

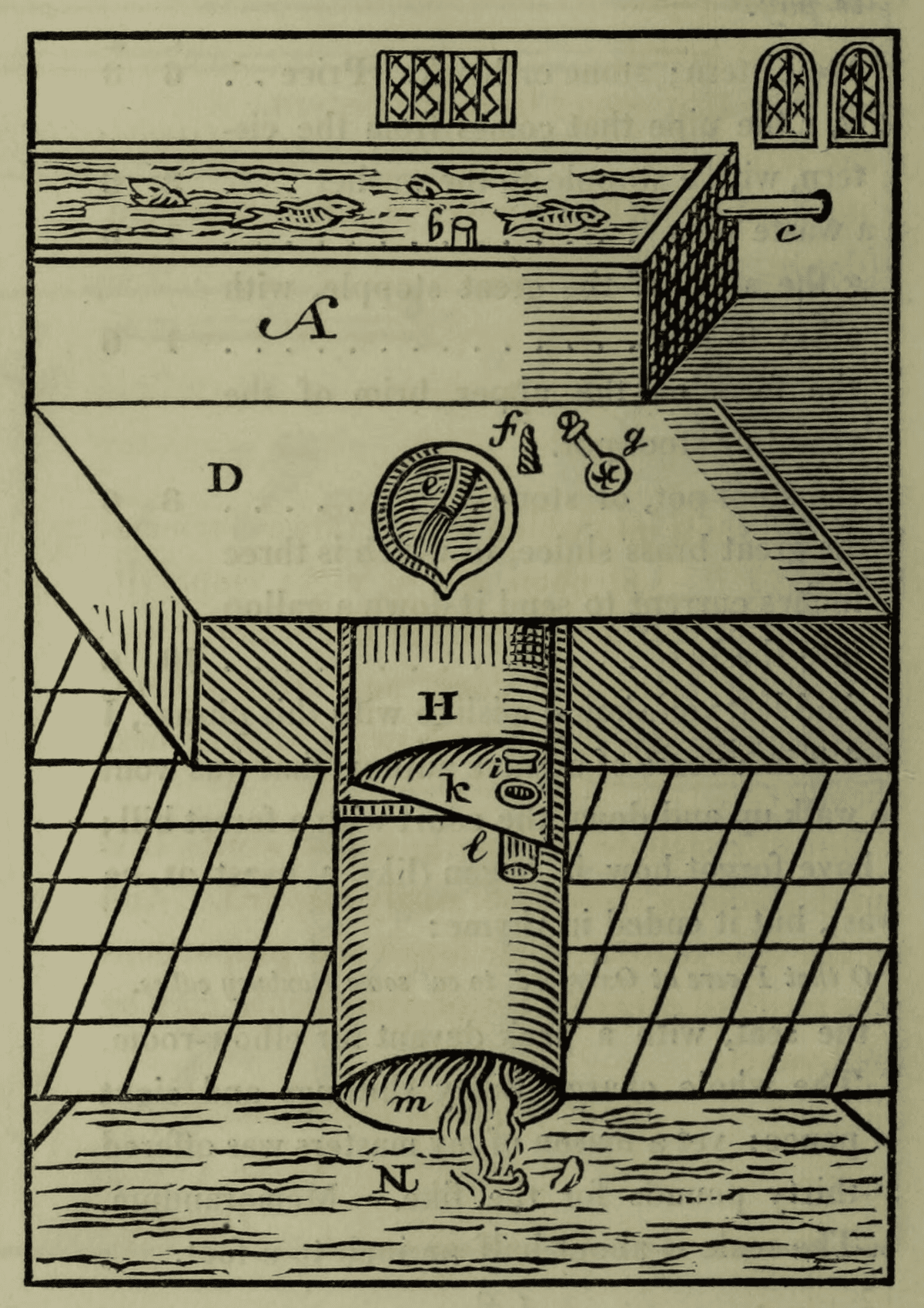

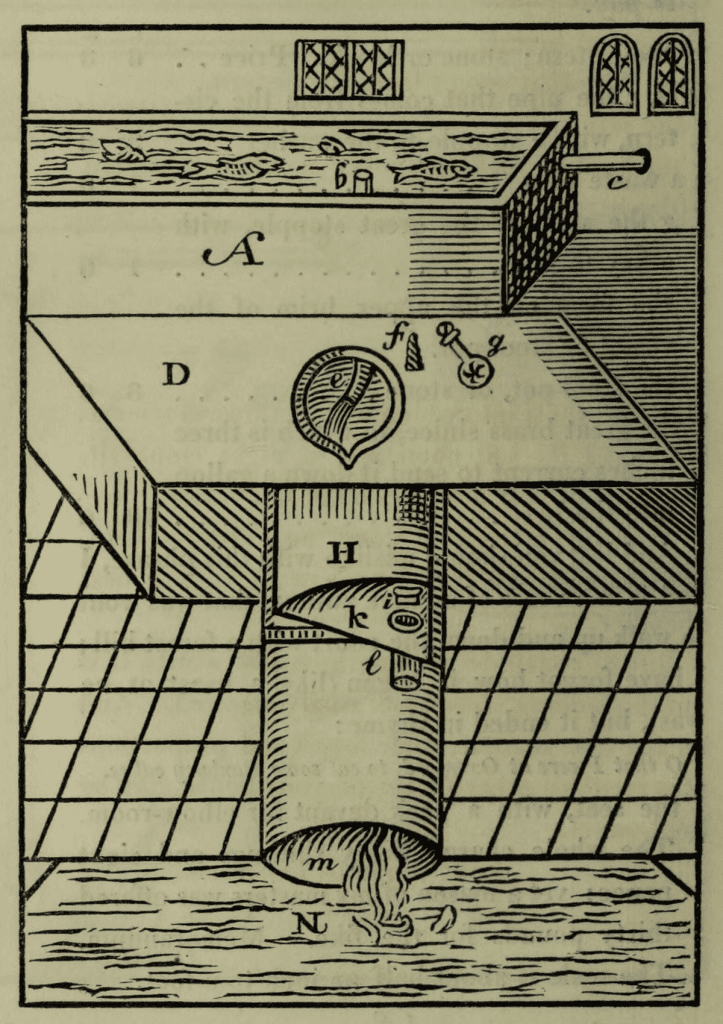

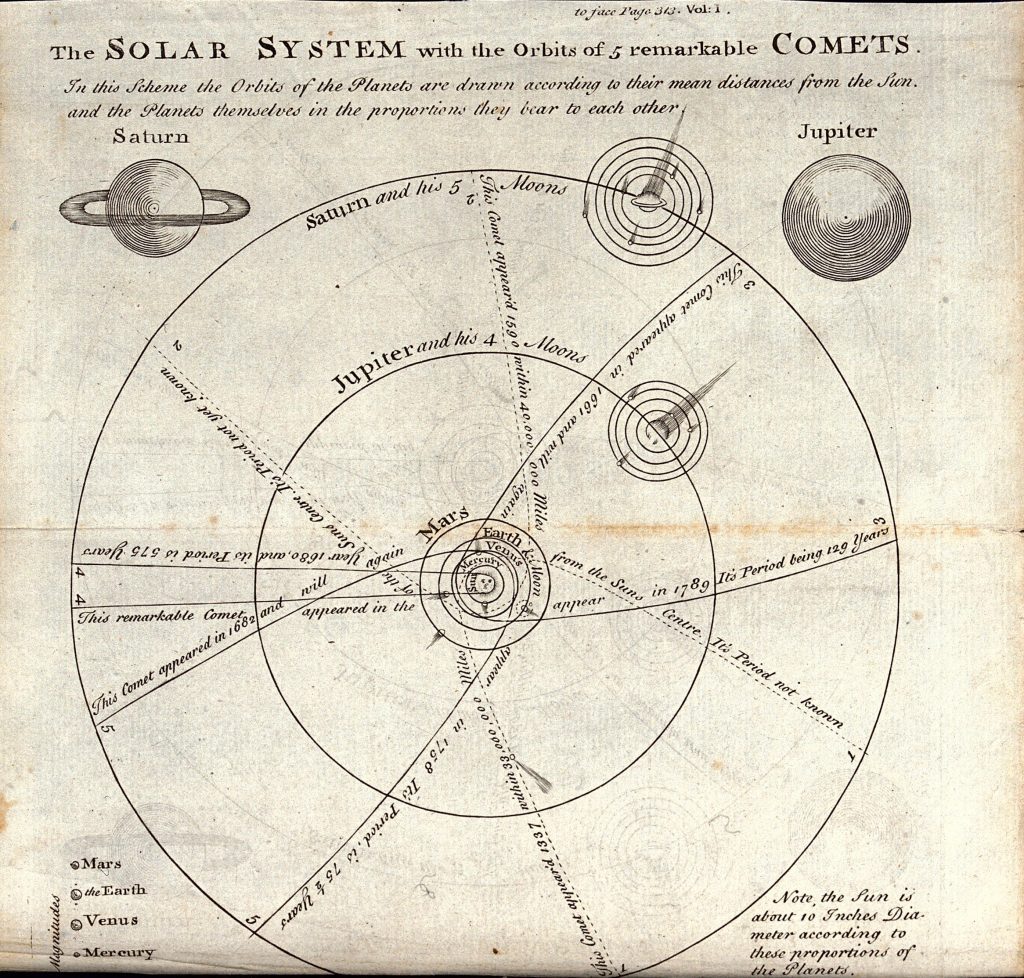

I’d say the most exciting part thus far has been getting to go through thousands of facsimile images of early printed books (including e.g. all incunabula on Early English Books Online) in search of graphic devices. It’s always exciting to consult primary sources, be it in situ or via a digital surrogate. I’m also very much looking forward to the results of our diachronic survey of graphic devices up to 1800 and to finding out more about the discursive strategies of book producers in presenting graphic devices and instructing the reader in using them.

Did anything unexpected or surprising come up? Did the project provide you with new research ideas regarding graphic devices or graphic literacies?

I’m not sure I would use the word ‘unexpected’, but it has definitely been interesting to see the distribution of different types of graphic devices in our data thus far, and I’m looking forward to finding out more about the relationship between graphic devices and genre / target audience. It’s also been fascinating to see some examples of devices that do not quite fit in with present-day conventions and definitions of graphic devices, and I’m hoping to take a closer look at some of these in the future.

Do you have any reading recommendations related to early graphic literacies and/or graphic devices?

This is such a multidisciplinary field that it is difficult to give just a few recommendations – it would have to be a lengthy reading list. But I would say one benefits from reading widely and being open-minded. One article I enjoyed reading last year was Elizabeth Rowley-Jolivet’s study on ‘The emergence of text-graphics conventions in a medical research journal: The Lancet 1823–2015’ (ASp, 73). Although both the medium and date of Rowley-Jolivet’s primary materials are outside the scope of EModGraL, I found that the analysis was very relevant for our interests. Since I usually focus on late medieval and early modern materials in my own work, I might not even have spotted this paper were it not for the project.

Mari-Liisa Varila & Aino Liira | Twitter: @mlvarila, @penflourished