The XII annual colloquium of Variantti, the Finnish network of researchers working on textual scholarship and scholarly editing, was held on Friday, 4 October 2019, at the University of Turku to foster interdisciplinarity between textual scholarship and translation studies.The theme trextuality encompassed textuality, transmission and translation, concepts central in both fields. In translation studies, trextuality means going beyond the source-target text pair and in textual scholarships, it refers to observing the transmission of texts across languages. Some fifty attendees heard eleven talks addressing trextual issues.

Tanja Toropainen discussed the continuum of editions and translations behind Codex Westh and its Ars Morendi part, which is a translation from German – except that the The Bible quotations are translations from Swedish. Sara Norja pointed out that like many of early English texts, also The Mirror of Alchemy is a translation – the source language of the various versions (Latin or French) can be deduced from how the alchemy-related terminology is translated. Niko Huttunen & Tuomas Juntunen explained that the forthcoming Finnish translation of The Bible for mobile platforms will have vocabulary different from what the audience is accustomed to because the language is made understandable for 20-year-olds.

multilingual transmission history of Robinson Crusoe.

Leena Eilittä discussed intertextuality in Herman Broch’s works; for example, Broch changed the title of his poem into Hille Mitternacht (A clear midnight) after having translated Walt Whitman’s A clear midnight into German. Marja Sorvari addressed the intertwinedness writing, writing in a second language, and self-translation through the example of two translingual authors, Zinaida Lindén and Polina Kopylova.

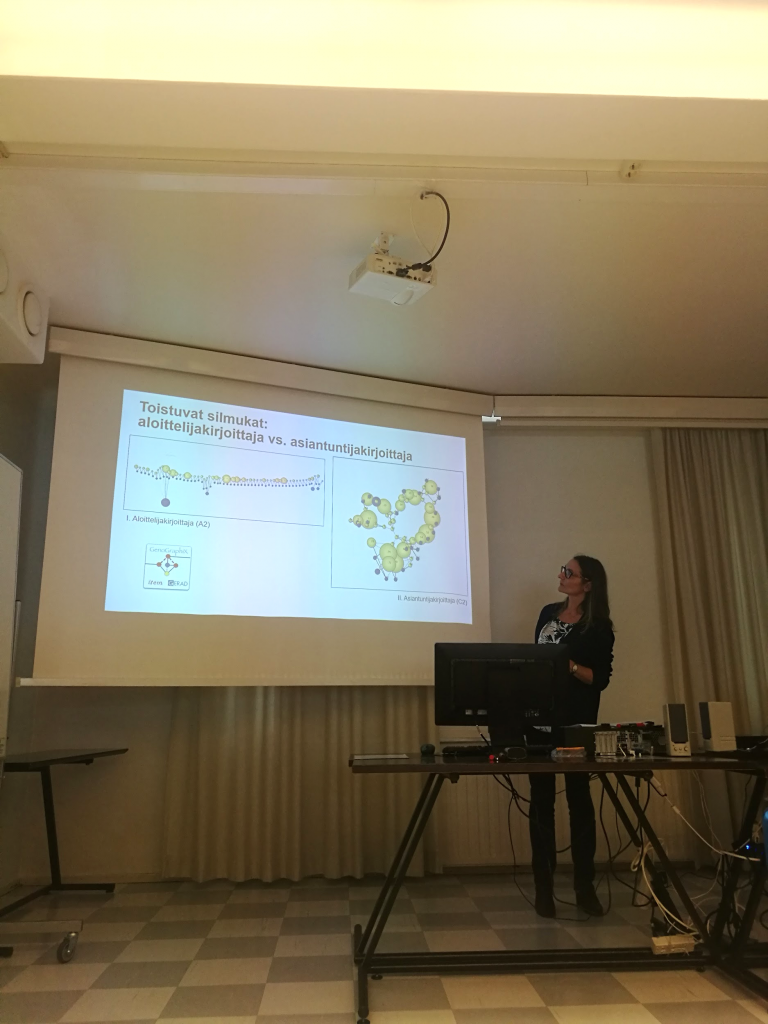

Instead of studying what changes in translation, Taivalkoski-Shilov showed how Friday’s way of talking remains unchanged in the Finnish Robinson Crusoe (re)translations even if translated indiretcly from English to German to Swedish to finally Finnish. Members of the Digilang project Christophe Leblay, Maarit Koponen, Maarit Mutta, Anna Salmela, Leena Salmi & Mikko Suhonen showed examples of text editing process visualizations using tools such as GenographiX: for example, A2-level writers proceed straightforwardly while C2-level producers make loops as they write and edit different parts of the text at different times.

Annamari Korhonen suggested that because something always changes when a text is translated, translating is creative even with pragmatic texts. Tuuli Ahonen demonstrated how a translator cannot translate the whole film if one of the modes – picture, dialogue, music, or sound effects – is missing because the subtitles are part of the polysemiotic whole that the modes together make.

Minna Seppänen & Outi Paloposki discussed how in the early 19th-century Ancient Greek literature was translated into Finnish more to show off one’s language skills than to produce beautiful Finnish translations. The day concluded with the perspective of a professional translator: Jaakko Kankaanpää shared his observations on the differences, such as replacing racist vocaublary with politically correct terminology, between various Finnish (re)translations of Agatha Christie’s novels, including his own ones.

Text and photos: Laura Ivaska