Author: Thomas Devaney

It’s an exchange to which I became rather accustomed last year. The slightly raised eyebrow. The question, “Oh, why there?” with just enough stress on the final word to signal a hint of incredulity. It was the more-or-less typical reaction when I told one of my US colleagues that I would be spending my sabbatical year, from 2019-2020, in Finland in order to work on a book about late-medieval and early modern Spanish history. In one sense, the surprise made sense; Finland is an atypical destination for America-based scholars of Spanish or Mediterranean history. And yet Turku was an ideal place in which to develop my ideas, to try out new ways of teaching, and to experience Finnish university culture from a fresh perspective.

I’ve spend most of my academic career in the United States; I earned my PhD at Brown University in medieval history and have taught at the University of Rochester, where I am now Associate Professor, for the past several years. But I’ve had contacts in Finland for about ten years, since I met Teemu Immonen at a graduate-student summer school in 2010. I then reconnected with Teemu and others from Turku (including Marika Räsänen, Reima Välimäki, and Meri Heinonen) at the International Medieval Congress in Kalamazoo, Michigan. I also spent a year as a researcher at the Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies (HCAS), from 2015-2016. That was when I first visited Turku, to give a presentation for TUCEMEMS.

And so, when I next had an opportunity to take a research leave from Rochester, I immediately thought of returning to Finland. The Fulbright Finland Foundation offers a range of fellowships for Americans to come Finland and for Finnish scholars to work at United States universities. In addition to providing the funding that made my time in Turku possible, the Fulbright program offered a community of people throughout Finland as well as several events that brought all of us together (including the American Voices Seminar, which took place in Turku in October, see the poster). Also interesting to me was that Fulbright doesn’t fund only research; their Scholars Program expects that a visitor will fully immerse themselves in the life of the university: teaching courses, giving lectures, and building collaborations that will last long beyond the fellowship year. Since I am a rather introverted person (perhaps another reason I feel at home in Finland…), to do all this well meant that I had to step outside my comfort zone in some ways and be ready to jump into new situations.

I also had to think about teaching in a Finnish context. Since I had never ever taught bachelor’s students outside of the United States, I was a little worried about how my “American style” of pedagogy would work. This was especially relevant since several people warned me that Finnish students can be rather quiet, and I prefer to engage my classes in discussion. My first lecture to students, “Materiality and Early Modern Catholicism,” was as a guest in Visa Immonen’s course on the Ecclesiastical Heritage of the Early Modern Period:

I quite enjoyed putting together this talk on a topic that was related to my research but involved an approach that differed from my usual. And, although they were indeed reserved, the students were (I hope) engaged.

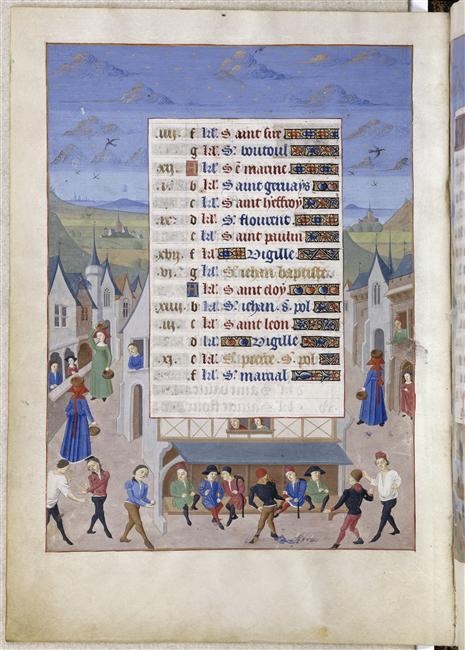

I also gave a guest lecture in Reima Välimäki’s course on how to use medieval sources. The kinds of sources I chose for this visit were not specific categories of documents. Rather I invited the students to think about urban space in all its medieval guises—maps, city plans, images, written descriptions, but also the spaces themselves—as providing insights into medieval culture. For instance, in thinking about this fifteenth-century illumination of an early form of tennis:

we might think about the repurposing of a town square, the relationship between private and public, and the modification of a home to accommodate sport. There is a chance that several of us might develop our lecture into a handbook for future students; I look forward to this project!

In October, I began my own course, titled “Europe and the World, from the Crusades to Columbus.” Our goal was to consider Europe’s place in broader world systems evolved between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries.This involved, first of all, questioning the origins of an idea of “Europe:” how did a shared identity come to exist between places as disparate as Finland and Portugal, Ireland and Greece? We also examined how encounters of all kinds (military, economic, religious, linguistic, and so on) had been conditioned by prior ideas. About thirty students attended the lectures, and we had many great conversations. My worries about an American style of teaching turned out to be overblown!

In addition to teaching, I spent a great deal of time working on my own research. The project is a study of the emotional and sensory experience of pilgrimage in early modern Spain. I hope to clarify how people understood and interpreted the feelings they felt when reaching a cherished destination or entering a sacred space, what it was like for them to be part of a crowd all laughing or crying or shouting or praying together. What did it mean to experience or witness a miraculous healing? Even thinking about or visualizing a shrine or a miracle could, according to early modern authors, lead to powerful emotions. Central to my approach is the idea that, although emotions have a biological aspect, the way we experience them is closely linked to cultural context. The project, then, is about more than pilgrimage; it is about early modern conceptualizations of emotion in general. Pilgrimage was, for many people of the time, a life-altering and –defining experience, one about which they wrote, a lot. And they often wrote about their feelings. Pilgrimage, therefore, provides an opportunity for us to better understand how they thought about those feelings.

One of the biggest potential challenges of working on an Iberian topic in Turku is access to sources. My project relies on so-called “miracle books” (histories of individual shrines that typically describe the shrine itself and its holy image, the miracles it has performed, and the annual pilgrimage) as well as theological treatises, images, literature, poetry, travelogues, and other early modern representations of pilgrimage. So I brought with me all the notes I had compiled during previous research trips as well as a big pile of books. I planned also to rely on digitized copies of texts online, at collections like the Biblioteca Virtual del Patrimonio Bibliográfico and the Biblioteca Virtual de Andalucía. For me, however, the process of writing is also the process of thinking. No matter how well prepared I think I am, once I start to write, I inevitably find that I need to read more, dig deeper, and explore new lines of inquiry. And so I’ve needed to regularly locate new materials. It was a pleasant surprise, therefore, to discover the riches available in the university library collections, both in print and online!

I could do this kind of work nearly anywhere, of course. A big advantage of being in Turku was the chance to exchange ideas and to collaborate with the other scholars. To that end, I was excited to participate in department research days and at meetings of the Vanhat ajat research group as well as TUCEMEMS. The topics of my own presentations included thinking about miracles as a way to mitigate negative feelings, traveller’s opinions about Spanish “passions,” and the relationship between sound and emotions. But I really enjoyed learning about topics as diverse as computational methods to determine the authorship of historical texts, the Council of Ferrara-Florence, representations of the nineteenth-century royal women, how we might use narrative theory to interpret the work of ancient historians, and so much more. There were other opportunities to share ideas; I wrote a brief talk about “The Use and Abuse of History in Contemporary American Politics” for the department’s Joulukoulu (thanks to Marjo for presenting it when my flights were delayed!) and another about the ins-and-outs of research funding in the US. Outside the circle of historians, I also gave a presentation in January for the Department of Geography’s “Think and Drink” series. Proffan kellari was a great place for the discussion about how segregation in fifteenth-century Córdoba contributed to an outbreak of violence; I had never before given an academic talk in this kind of venue.

Outside of work, I appreciated the chance to get to know Turku better. I’d visited before, but only for a weekend. Walks and runs along the river, past Koroistenniemi and into Virnamäenpuisto, were a regular weekend treat and I made several trips into nature outside of the city as well, to Vaarniemen torni:

Kurjenrahka:

and Teijo. And, of course, I made sure to visit Ruissalo and Naantali. In Turku itself, I enjoyed exploring the bars and restaurants (Kaskis!) and made a point to visit all the seasonal events, like the Christmas concerts, the Independence Day student procession, and the Turku 100 celebrations.

I had plans to do quite a lot more exploring, especially as the weather improved in spring and summer, but the Covid-19 pandemic intervened. When everything shut down, I had been about to travel to Stockholm for a weekend and then to Helsinki for a conference featuring all the Fulbright fellows in Finland. Those plans were cancelled, and the course I was about to begin teaching, about the early modern European witch hunts, moved online. Like all of us, I found this to be an uncertain time. No one knew what would happen next, borders were closing all over the world, and the Fulbright authorities were strongly encouraging all grantees to return home as soon as possible. Although I initially thought to remain in Finland, I was concerned about family in the United States and was unable to know when travel restrictions might end or whether all air travel might cease entirely. I decided that the wisest decision would be to leave Turku early. My flights to the United States in early April were surreal, with deserted airports and almost empty planes:

I arrived safely, though, and the whole situation was made much easier by the flexibility and understanding of everyone in Turku and at Fulbright Finland.

Yet I did not end my association with the University of Turku at that time. I carried forward with the witch-hunts course, which had already drawn a lot of attention from students (110 students had initially enrolled in the course, and a large percentage of these completed it). As the first experience in remote learning and teaching for me, and probably for many of the students, this was a bit of an experiment. But it was a generally successful one. Much of our conversation happened on Moodle discussion forums and I was pleasantly surprised to see the perception and detail with which the students engaged the various topics. This is, of course, a very different kind of discussion that one in the classroom, allowing everyone more time to think and to process others’ ideas. And it makes me wonder if I should include such ways of interacting in all my courses, even after the need for remote learning has passed. All this led to creative, insightful final essays. From the United States, I also participated in a research seminar at Åbo Akademi via zoom and, with a bit of trepidation, submitted the teaching demonstration for my docent application as a recorded lecture. Thankfully, this was successful!

I haven’t come close here to talking about all the experiences, adventures, and connections from my months in Turku. That would require a much, much longer blog post. But, even so, my early departure meant that a lot did not happen. I had hoped to see Vappu and the Paavo Nurmi games. I expected to travel through the Archipelago and perhaps spend Midsummer in Lapland. I also went to very few conferences outside of Turku during my first months there (though I did get to connect with colleagues in Tampere twice) because I had several scheduled for April and May. These may, if all goes well, happen next spring. And there were other collaborations (for instance, with the Centre for the Study of Christian Culture) that had just been beginning in March. But though we have to maintain connections online for now, I like to think that everything has merely been delayed, not cancelled. I hope to be able to return to Turku for a few weeks in autumn or winter. And I will be a visiting fellow at the Centre of Excellence in the History of Experience in Tampere in May and June 2021 – I will be sure to visit Turku then! And, meanwhile, it turns out that I don’t have to entirely leave the Finnish experience behind…

Thomas Devaney spent the academic year 2019–2020 as a Fulbright Professor at the Department of Cultural History. He has the position of Associate Professor at the University of Rochester.

Vastaa